1662 Missed opportunities

Her Courage Rises: 50 Trailblazing Women of British Columbia & the Yukon

by Haley Healey (text) and Kimiko Fraser (illustrations)

Victoria: Heritage House, 2022

$22.95 / 9781772034257

Reviewed by Veronica Strong-Boag

*

In the last half century, women’s history has been a success story in Canada, as in other lands. Whether judged in terms of enriching and diversifying understanding of the local and global, in the number of scholarly and popular publications and prizes, the introduction of specialized courses, the integration of women and gender into more general stories or experimentation with new perspectives and methodologies, it has heightened the bar for excellence in the presenting of the past.

In the last half century, women’s history has been a success story in Canada, as in other lands. Whether judged in terms of enriching and diversifying understanding of the local and global, in the number of scholarly and popular publications and prizes, the introduction of specialized courses, the integration of women and gender into more general stories or experimentation with new perspectives and methodologies, it has heightened the bar for excellence in the presenting of the past.

Scholarly advances have often been preceded, accompanied, and followed by well-meaning and often moving popularization of a gospel of female worthiness and talent. N. de Bertrand Lugrin’s The Pioneer Women of Vancouver Island, 1843-1866 (1928) and Jan Gould’s Women of British Columbia (1975) are two good examples of non-scholarly but valuable reminders of the distaff side of the province’s life. Such interventions into public narratives that overwhelmingly favour men and rarely doff even the proverbial cap to non-elites have often been inspirational for more academic studies.

Lugrin’s and Gould’s pioneering contributions appeared before much scholarship in women’s history. Would-be successors, such as Haley Healey‘s Her Courage Rises, in seeking to bring to life women “who lived fearlessly, unapologetically, and intentionally” (p. 6) for popular audiences in the third decade of the 21st century, can in contrast draw on a wealth of information and arguments in readily available theses, articles, and books, not to mention the world wide web. If they do their homework, today’s popularizers of women’s history have much to contribute to a knowledgeable citizenry.

With some half century of scholarship to provide both meat and sinew for Her Courage Rises, what do we find? Mounting disappointment. First of all, the criteria for selecting 50 figures are never spelled out, although selection requires at a minimum some attachment to BC or the Yukon, although sometimes this appears to mean little more than passing through (Brenda Mulrooney). Healey categorizes her choices as ‘writers’, ‘photographers and artists’, ‘entrepreneurs’, ‘miners’, ‘adventurers’, doctors and scientists’, brave pioneers and homesteaders,’ ‘politicians’, and ‘athletes’ but many figures do not fit neatly into such neat boxes (for instance, Mary Ann Gyves/Tywa’Hwiye Tusium Gosselim might just as easily be treated as part of the ‘helpers and healers’ or ‘entrepreneurs’ rather than in ‘brave pioneers and homesteaders’). In fact, the slightness of all entries, with key information often missing, raises questions about the accuracy of many of the assigned categories.

Some choices are well-known (Emily Carr; Rosemary Brown) and others far less so (Lilian Bland) and accounts range equally widely with some women receiving a scanty page (Delina Noel) while others get more than double the treatment (Barbara Touchie/ (Sičquuʔuƛ). No explanation for the varying length of entries is given and size does not reflect relative significance or contributions or even the extent of readily available material.

In keeping with the advance of scholarship, 18 of the 50 biographies — or 19 or 20 if you count the Doukhobor Anna Petrovna Markova or Nellie Yip Quong who married a Chinese man — are racialized women. Most are First Nations (Edith Josee) or Metis (Sophie Morigeau) with a handful of Asian (Victoria Chung) and African Canadians (Emma Stark). Also reflecting today’s priorities, Healey acknowledges racism and resistance as integral to many women’s lives, although associated hatred and rage remain (politely) hidden. However, in contrast to contemporary scholarship’s insistence on a broad range of female experience, Healey only makes this explicit with regard to race. The LGBTQ community is conspicuously absent, although some representatives may have crept in without acknowledgement. Nor is any woman identified with a visible disability. Still more significant is the failure to confront class and rank as constituting part of BC’s long-standing diversity in both Indigenous and newcomer communities. Social status framed life opportunities for women at the top (Florence Edenshaw Davidson and Sara Ellen Spencer) and at the bottom (Kate Carmack/ Shaw Tláa and Catherine Schubert) but its relevance is largely ignored.

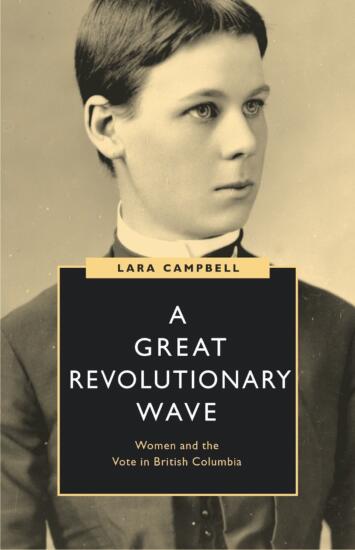

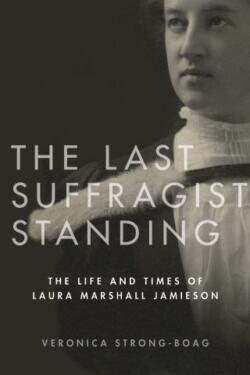

Given BC’s special prominence, at least in the Canadian story, with regard to female suffragists, politicians, and unionists, the limited inclusion of such women (only Martha Black and Rosemary Brown) is especially extraordinary and should have been addressed by the press editors. The omission of any reference to magisterial volumes by Lara Campbell (The Great Revolutionary Wave: Women and the Vote in British Columbia, 2021 — reviewed by Phyllis Reeve, Ed.) and Joan Sangster (One Hundred Years of Struggle: The History of Women and the Vote in Canada, 2019 — reviewed by Barbara Messamore, Ed,), recent biographies of politicians and activists such as Laura Marshall Jamieson (reviewed by Patricia Roy, Ed.) and Mary Ellen Smith (reviewed by Phyllis Reeve — Ed.), or lively interventions in labour history such as “18 Historic Milestones and Incredible Women in BC Labour” by the BC Labour Heritage Centre is simply unacceptable in the 2020s when the author promises to highlight women who have lived “fearlessly, unapologetically, and intentionally.” The (highly) “Selected Bibliography” includes a reference to a “full list of resources” on the publisher’s website but in fact the link does no more than list other Heritage House volumes. Not good enough.

In short, the stories told in this volume, with their frequently exaggerated, undocumented and even misleading claims, are simply the wrong place to start if you want to discover the past for women in BC and the Yukon. Her Courage Rises offer little guidance to the rich narrative widely available in a multitude of formats. The publisher would have done the public far better service by simply reprinting old stand-bys such as Pioneer Women of Vancouver Island and Women of British Columbia.

*

Veronica Strong-Boag is a Member of the Order of Canada, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, Professor Emerita in Social Justice at UBC and Adjunct Professor in the Departments of History and Gender Studies at the University of Victoria. She has received the Tyrrell Medal in Canadian History from the Royal Society of Canada (2012) and numerous other scholarly prizes including the Canada Prize in the Social Sciences and the Klibansky Prize in the Humanities. She has served as president of the Canadian Historical Association and as BC representative on the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada and received a Doctor of Laws, honoris causa from Guelph University in 2018. Her latest books are The Last Suffragist Standing: The Life and Times of Laura Marshall Jamieson, 1882-1964 (UBC Press 2018) and A Liberal-Labour Lady: the Life and Times of Mary Ellen Smith (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2021). In addition, she serves as the General Editor of the UBC Press 6-volume series Women Suffrage and the Struggle for Democracy, on the City of Victoria’s Heritage Panel, is the former director of the pro-democracy website, womensuffrage.org and a former member of the Editorial Board of Voices/Voix. Veronica Strong-Boag lives in Victoria.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1662 Missed opportunities”

Dear Veronica Strong-Boag

I enjoyed reading your review of Haley Healey, “Her Courage Rises”. While I think the young author needs to be acknowledged for effort and industry, your review encourages me to revisit one person left out of almost every biography or compilation of BC women’s history. Alice Ravenhill was a major figure in her time, and she has been steadfastly ignored for many years. Her research and study in Indigenous Arts and Crafts in BC has served more as an example of eugenics gone bad and disdain for the English.

Thanks, perhaps I will return to Alice.

And, belatedly, I realize age does not have that much to do with industrious effort. I apologize to Haley Healey, the author.