1626 The justice imagination

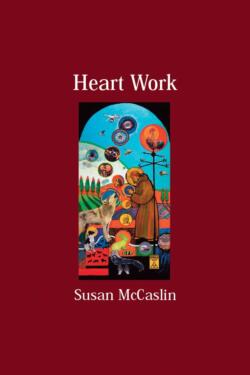

Heart Work

by Susan McCaslin

Victoria: Ekstasis Editions, 2021

$24.95 / 9781771714020

Reviewed by gillian harding-russell

*

In Heart Work, Susan McCaslin embraces a way of seeing that centres on the heart, both as an image and an idea, and as it shapes consciousness. Just as the cover artist, Betty Spackman, divides her art installation into panels, McCaslin creates four suites: while the first sequence is inspired by mediaeval mandala in relation to Hildegard of Bingen’s mystical thought, the second series is prompted by John Keats’s letters. The third suite pairs poems about the devastation following the Cariboo, BC[1] fires in 2017 with Mark Haddock’s photographs, and the fourth suite meditates on our contemporary world plagued with climate change and a pandemic. By turns erudite and lyrical, McCaslin’s minimalist verses are sometimes topical and always engaging.

In Heart Work, Susan McCaslin embraces a way of seeing that centres on the heart, both as an image and an idea, and as it shapes consciousness. Just as the cover artist, Betty Spackman, divides her art installation into panels, McCaslin creates four suites: while the first sequence is inspired by mediaeval mandala in relation to Hildegard of Bingen’s mystical thought, the second series is prompted by John Keats’s letters. The third suite pairs poems about the devastation following the Cariboo, BC[1] fires in 2017 with Mark Haddock’s photographs, and the fourth suite meditates on our contemporary world plagued with climate change and a pandemic. By turns erudite and lyrical, McCaslin’s minimalist verses are sometimes topical and always engaging.

In “Hildegard Meets St. Francis and the Wolf,” an ekphrastic poem inspired by the ninth panel of Betty Spackman’s fifteen panel installation, “A Creature Chronicle,” McCaslin views the universe in its multiplicity as having an aesthetic in common with collage images, whereby “lines and circles play hide and seek/ beneath a rooster’s weathervane:”

Suddenly we are here now

with haloed brother Hare

Francis and his pal Bro Wolf

This ancient holy scene finds an echo in the contemporary “under the Wolf’s belly squats// a pert everyday dog/ golden nimbused,” and so, today’s ordinary partakes of the sacred. That the ninth panel which inspires this poem also serves as the cover design for the collection seems to indicate the poem’s pivotal importance in the poet’s vision with its theme of love for all creatures.

For all the diversity of material and sources of inspiration across time and historical thought, the poems in Heart Work come together most satisfyingly in the title poem “Heart Work.” Here the image of the heart figures graphically at its centre:

Praise to the bi-valved flesh-wrapped organ

the heart heart ark site of heartwork channeling

nourishment to flesh’s crannies

Love’s courteous courier humble sage

The “bi-valved” heart acts in McCaslin’s vision as a metonymy for the dichotomy of body and spirit whereby there is a confluence as the body (the physical senses) rise up to supply the mind in its magnanimous response. This poem with its expanding association and wordplay has a spoken word quality as well as embodying the visual strengths of typographical verse as seen on the page. Here, adding a lovely personal touch, another echo of Francis of Assisi and his “pal Bro Wolf” presents itself in the speaker who walks her dog along the Fraser, “her animal heart and mine in sync.”

In the second suite, “Negative Capability Suite,” McCaslin draws lines from Keats’s letters as prompts for poems harnessed by the Romantic poet’s concept of “negative capability” to create a richly allusive sequence. Keats’s self-coined term, “negative capability” – which he understands as the ability to accept “uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after reason or fact” – to me translates as something like generosity of mind and spirit through faith, and so McCaslin brings the reader to envision a spiritual world of imagination as Keats might have. Extending its application, McCaslin interprets Keats’s notion of “negative capability” as imagination that lends itself to the spiritual embodiment of truth through poetry, and in McCaslin’s vision, to a “yearning backwards into presence.” In a mirroring of Keats’s “Adam’s dream,” in which “imagination is called truth,” McCaslin finds a feminist counterpart in Eve’s version:

Eve woke from her dream

and found it Imagination

deep dream truth – fire music

not drawn from a rib

but from her own gaze

as into the eye of a pond

that gazed back, hazel blue.

While Adam discovers pragmatic “fire music” drawn from a physical “rib,” Eve’s experiences are more mystical: “from her own gaze” into “the eye of a pond/ that gazed back, hazel blue.” Interestingly, “the eye of the pond” suggests an anthropomorphic impulse in female meditation with nature seen as the “eye” that “gazes back, hazel blue” and that implies a beauty as well as a reciprocity in nature as it rewards the viewer.

When Keats, aware of the doctor’s grim diagnosis that he would soon die, retreats to Italy, he describes his sense that he is already leading “a posthumous existence,” and McCaslin applies this ominous feeling that the poet personally experienced to what faces humanity today, while we are a species “cruel and kind” who seek to “destroy the base” by which we live:

yet breath that circulates in body-mind

earth-fettered, earth released, helps up forgive

then sing farewells and greeting to the now

through love I always made an awkward bow.

The last italicized verse – drawn from Keats’s letter in the manner of a glosa – reflects the poet’s failure of spirit and hopeless apology when faced with his inability to meet life’s challenges and, most of all, the prospect of his own death; and in McCaslin’s application to a general world malaise that afflicts us today plagued by climate change and a still lingering pandemic, the echoed line is equally grim, both effective and affective.

In the third suite or “panel,” “Cariboo Fires, 2017” McCaslin writes terse and moving verses about the horrific fires that destroyed a large area of British Columbia near the poet’s own property. Although her husband’s family cabin was spared due to the “valiant work of firefighters,” as she explains in a short preface to that section, the boathouse was destroyed as well as many hectares of forested land. The verse style ranges from a format of a-verse followed by b-verse with the caesura (in the Anglo-Saxon tradition) in one poem to more contemporary minimalist verse that attempts to enter the stranded animals’ experience in the reduced scenery where they find themselves. The speaker’s identification with the animals emerges in the details about the setting and through the stark simplicity of the lines:

fireweed will regenerate

but the forest?

controlled burns help

by devouring kindling

yet what of woodland caribou

lichen starved

snakes and frogs scrambling?

Here, an off-shoot of Keatsian “negative capability” might be empathy, whereby the speaker identifies with a situation alien to her own. In an earlier verse, we see opportunists hunting for moose when the animals have nowhere to hide among the sticks of trees, and so McCaslin makes us feel for all such beleaguered creatures. Moreover, Mark Haddock’s photographs of the devastation add a graphic immediacy to the poignant verses.

In the fourth suite, “Corona, Corona,” McCaslin directs her visionary eye to the recent pandemic. From the poet’s ironic ode-like address in the section’s title poem “Corona Corona,” with tongue-in-cheek lack of respect – “You’re just one of many sub-streams – SARS, Spanish flu, Bubonic Plague – to her placing today’s coronavirus in the perspective of Julian of Norwich’s emblematic hazelnut that in its dormancy and promise represents the world, and Dickens’ “It was the best of times, the worst of times,” McCaslin delights the reader with the richness of historical and literary allusions unravelling wherein Julian of Norwich’s hazelnut may in its inert and dormant stage be the seed for tomorrow’s prospering tree after a metaphoric winter that is after all a period for hibernation and germination before spring’s rebirth:

Taking a breath as the wild creatures return

we peer through the global membrane

ears cupped to the hermit thrush’s spiralling song

held in the arc of the great blue heron’s flight.

Just as civilization may be seen to catch its breath during the restrictions of the pandemic so that nature has a chance to recuperate, the poet witnesses all around her today “small acts of compassion” as the “heart work” of what she terms the “justice imagination,” with prayers for “collective transformation.” As during Dickens’ “best of times, worst of times,” humans may be driven by hard circumstances to creativity and discoveries in science, with or without emotional maturity.

For all the diversity of subject matter across history, literature, and nature within this wise and elegant volume, there remains a common theme encapsulated by what the poet terms “heart work,” which may be described as the fruit from a coupling of spirit and imagination. I am fascinated by McCaslin’s erudite reach and ability to synthesize swatches of material over centuries into the “walnut shell” of an organic whole with four suites nested between. Here is a volume of slim, pithy verses that affirm that the human spirit may be brought to its senses through the heart. I hope it might prove true.

Editor’s note: see here for an interview with Susan McCaslin on writers radio.ca

*

gillian harding-russell is a Saskatchewan poet and reviewer who lives on Treaty 4 territory. She has five poetry collections published, the most recent In Another Air (Radiant Press, 2018) and Uninterrupted (Ekstasis Editions, 2020), and a chapbook, Megrim (The Alfred Gustav Press, 2021). Both full-length poetry collections were shortlisted for Saskatchewan Book Awards. In 2016, a poem sequence Making Sense won first prize in Exile’s Gwendolyn MacEwen Chapbook Award. She has a B.A. (Hons) and M.A. from McGill and her Ph.D. (in English Literature) from the University of Saskatchewan. Editor’s note: gillian harding-russell has recently reviewed books by Margaret Atwood, Patrick Lane, and Yvonne Blomer for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endotes:

[1] Editor’s note: Susan McCaslin points out that BC’s Cariboo district “has been misspelled since the Gold Rush days and been universally adopted. This is because the original settlers misspelled it and the spelling has stuck to this day.” See this link.

One comment on “1626 The justice imagination”

Thanks to both Richard Mackie, and fine reviewer gillian harding-russell for their diligent service to writers, writing communities, and readers in BC and beyond.