1614 The hand reaches out

Art of the Northwest Coast: Second Edition

by Aldona Jonaitis

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2021 (first published by Douglas & McIntyre, 2006). (Also published by University of Washington Press, 2021).

$38.95 / 9781771623063

Reviewed by Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa

*

We entered the digital age 30 years ago this year when the Internet became a public network. That’s almost two generations ago. Long enough for us to experience the delight of search engines to the point that the thrill has faded, replaced by nonchalance. The word Google has entered the Oxford English Dictionary. Indeed. Google it.

We entered the digital age 30 years ago this year when the Internet became a public network. That’s almost two generations ago. Long enough for us to experience the delight of search engines to the point that the thrill has faded, replaced by nonchalance. The word Google has entered the Oxford English Dictionary. Indeed. Google it.

The Internet has since deluged us with an overabundance of data and information. What we now value is knowledge — sorting the wheat from the chaff, the significant from the superficial, the profound from the shallow, the expert from the amateur. If we can find this in a book we cherish it. The Art of the Northwest Coast by Aldona Jonaitis is one of those books.

In this digital age, where the constant flow of information is too overwhelming to store in one’s mind, we have shifted from memorizing knowledge to knowing where it can be found. Art of the Northwest Coast is one of those storage sites that resembles a library constructed by a reference librarian who has carefully curated and brought together history, politics, culture, and art through time and into one book. In fact, Jonaitis is a curator, with over fifty years of working in the field of Northwest Coast Indigenous art and producing a half dozen plus books on the subject. In many ways Art of the Northwest Coast is a survey history of British Columbia and the adjacent Pacific Northwest coast looked at from a lens of art, from pre-contact times through to current innovations.

The first edition was published in 2006, and the author’s knowledge and over a dozen issue-laden years later explains why this second edition is warranted. In recent years we have entered a new minimalist era involving the decluttering of our homes in an attempt to bring “joy.” Even our books have been “KonMari’d” — gathered, categorized, scrutinized, and discarded if they fail to meet the “joy” factor. As a result, many home libraries have been culled to the bare essentials. Art of the Northwest Coast is an essential book in the library of anyone interested in art and/or the Northwest coast. The book has been updated, includes more women artists, expands on artistic developments since the 1960s, and includes a new chapter on contemporary and innovative works.

Jonaitis’s expertise in the northern coast shines through with more emphasis on central and northern coast arts and slightly less for the southern coast.

Throughout the book Jonaitis and the artists carve new ideas for us to ponder. A good example is the term “traditional,” which implies a colonialist view that fixates on the past, as if art done then was the epitome that should be strived for, and that rejects artistic change rather than respecting customary practices and evolving new artistic expressions. The author suggests the word “customary” as more appropriate, much as the Maori (and many Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesian countries have done (for example, Papua New Guinea’s Pijin uses Kastom).

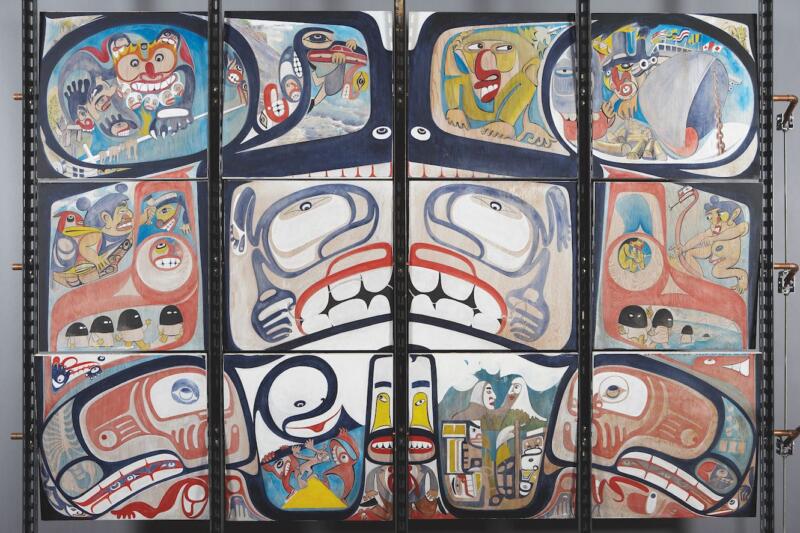

Another example prompting contemplation is from the artist Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas (think Haida Manga) suggesting the use of the word “frameline” in inviting the viewer into an entranceway to new experiences, rather than “formline,” which implies a fixed all-knowing view. Two ways of looking at those black lines in northern art: one as opening up and one as closing in.

Jonaitis shows us alternative ways of looking at objects. Take for example a Chief’s Chilcat robe which we often see hanging flat or worn at a ceremony, but when a Chief lies in state with his blanket wrapped around him, Jonaitis suggests “this representation of a lineage’s history, wealth, and power was embracing the chief, who became one with the lineage’s crest,” and “he became a new hybridized being that shared a body.” She then goes on to offer yet another view, that a worn Chilkat blanket could also be seen as a bentwood box, “a container that also illustrates its subject being with two faces on four sides.”

Jonaitis has done a remarkable job of showing how political, economical, and social spheres impacted art. One example she gives is the fur trade, which changed the wealth of individuals and families leading to an increase of potlatches and new art to enhance status. And when the smallpox epidemic devastated the Haida population there were few survivors to commission regalia, houses, and totem poles. That, along with colonial pressure to abandon their traditions, caused surviving artists to produce art targeted at outsiders: souvenir art.

The impact of smallpox all along the Northwest Coast is an area I felt the book could have made more of. With population declines in the range of 70 to 90 per cent, the impact would have been nothing short of a disaster to the culture, society, and economy, let alone the region’s art.

While Jonaitis discusses the use of the Coast Salish sxwayxwey mask used in purification dances, some Northwest Coast historians suggest smallpox was influential in its development and diffusion from Stó:lō territory to more distant Coast Salish communities, and also further north into Kwakwaka’wakw territory. Given that the sxwayxwey mask is the only Coast Salish dance mask, and that women shared the privilege of owning and using the mask, a little more text on the subject would have provided more context to that art.

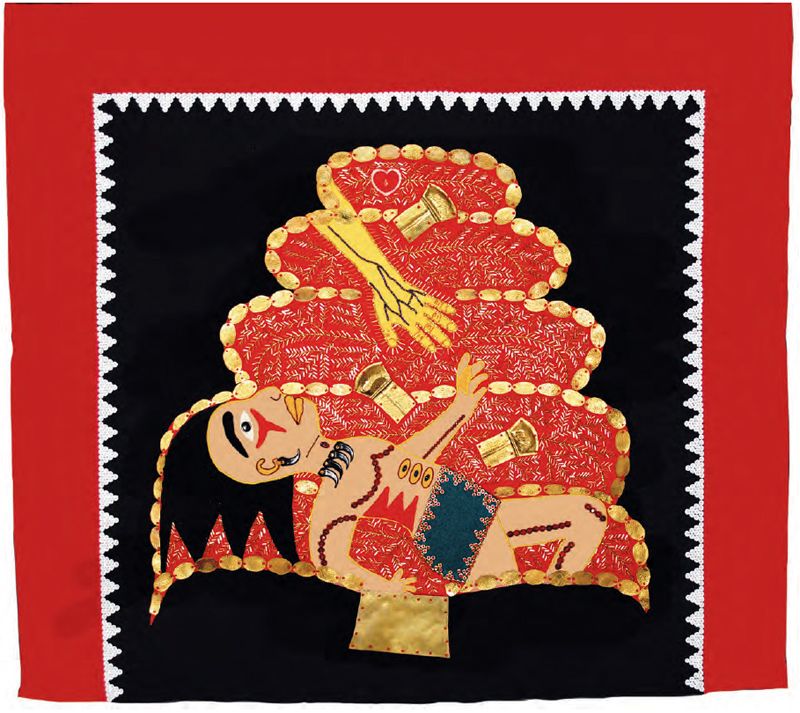

In the second edition, Jonaitis added more “women’s art” such as basketry and textiles. I enjoyed reading and seeing Haida weaver Lisa Telford’s cedar bark Pocahaida dress, a wry comment on Disney’s Hollywood portrayal of Pocahontas. Likewise, I was grateful to learn about Lani Hotch, the director of the Jilkaat Kwan Heritage Center in Haines, Alaska (I had to Google to find the location), who worked with a group of women to weave “the Klukwan Healing Robe” “to restore the community’s souls from the influences of western acculturation” (this is worth Googling).

Missing, however, is Jut-ke-Nay Hazel Wilson, Haida, who has produced remarkable button and appliqué blankets, and who deserved a mention, for example for her 17 blankets that tell the stories and myths of the golden spruce (and more recently, Haida history robes). Having said this, where does a survey book stop? Just how much detail can fit into one book? These are minor criticisms, but perhaps something that can be addressed in another edition in another ten years, and I say this encouragingly.

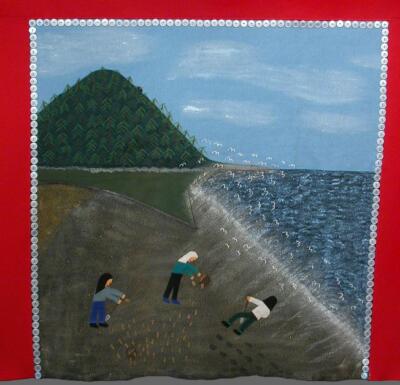

The most joy was sparked by the last chapter, “Innovation, Experimentation, Decolonization,” a captivating fifty pages on art that disrupts preconceptions, gives us pause to question our assumptions, and visually demonstrates art forms that are alive, evolving, and reflecting current issues. Examples include Yahgulanaas, who creates art in that littoral space in between two world views and opening up what he calls a [playful] third space for thinking about issues.

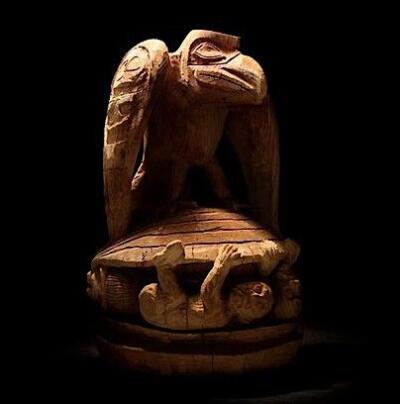

Nicholas Galanin, a Tlingit and Unangax̂ artist and “master of irony,” directed a non-Indigenous person to chainsaw Raven and the First Immigrant, a play on a replica of Bill Reid’s masterwork The Raven and the First Men. This was then placed outside the Museum of Anthropology at UBC, looking in at Reid’s carving “as if in conversation.” Google once again came in handy to read and see more, to consider the carvings and the ironic contrast between the two.

Jonaitis has a skill at being able to discern and describe art, not just the details, but the meanings that open eyes and minds to that “third space understanding.” She also provides sparks of details, like the fact that Clarissa Rizal — Tlingit weaver, printmaker, singer, writer, book illustrator — was also in Preston Singletary’s band Kau.éex. Who knew? Google Preston Singletary, a Tlingit glass artist who produces “customary” works in modern three-dimensional glass — or, better yet, read one of the books on him and his spectacular glass artwork: Preston Singletary: Echoes, Fire, and Shadows (2009) or Raven and the Box of Daylight (2019).

I found the whole of Art of the Northwest Coast: Second Edition well-researched and engagingly written with a profusion of illustrations. The captions and explanatory notes provided valuable context and in-depth analysis.

Of course the book, even at 388 pages, cannot possibly encompass the entire topic of Northwest Coast art, but it will spark joy in you and make you want to learn more. Read it with your tablet, smart phone, or computer nearby; you will be inspired every few pages to Google deeper, find out more, see more illustrations — and to thank the Internet for being there to complement this admirable book.

*

Retired from Vancouver Island University where she held the position of Director of Research Services, Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa now spends much of her time studying Coast Salish textiles. Along with a MA in Educational Technology, she holds a Master Spinners Certificate. She is a Research Associate with the Smithsonian and with VIU. She has worked with various museums including: the British Museum, Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, the RBCM, MoA and the Burke Museum in Seattle in helping to identify yarns, fibres, tools and techniques used to create the yarns. She was instrumental in identifying a rare blanket in the Burke Museum confirmed to be made of woolly dog hair. She has given many presentations and workshops on the subject of Coast Salish spinning and textiles to Coast Salish spinners and weavers and has written articles on the subject for magazines such as Selvedge, Spin-Off, and Ply — and for BC Studies about the use of diatomaceous earth in Coast Salish blankets. She lives on Protection Island, BC, in Snuneymuxw territory. Editor’s note: Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa has also reviewed books by Dempsey Bob, Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse & Aldona Jonaitis, and Leslie H. Tepper, Janice George, & Willard Joseph for The British Columbia Review, and she has has contributed a tribute to Bill Holm.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1614 The hand reaches out”

What a wonderful review! It makes me want to get a copy of this book as soon as possible — and also to spend a time on Google! Thanks for this.

Thanks for this Carol. Be careful with google, it is so full of rabbit holes—good ones and bad ones—you may get lost forever.

Liz