1531 High end mischief

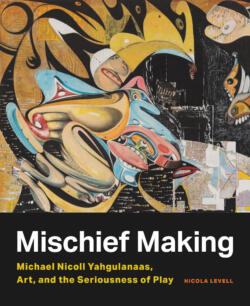

Mischief Making: Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, Art, and the Seriousness of Play

by Nicola Levell, with a foreword by Nobuhiro Kishigami

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2021

$29.95 / 9780774867368

Reviewed by Victoria Wyatt

*

Haida artist Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas explains, “I am committed to the idea of human hybridity as a good thing: difference is a fertile edge between ocean and river, a delta of possibilities” (p. 16). In Making Mischief: Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, Art and the Seriousness of Play, visual anthropologist Nicola Levell documents how Yahgulanaas’ art advances this positive view of hybridity. She explains, “Yahgulanaas is serious about the potential of hybridity, as an identification, aesthetic and strategy to elicit reaction and challenge established hierarchies, attitudes and stereotypes” (p. 8). Yahgulanaas mobilized this theme when he synthesized Haida two-dimensional design and Japanese graphic art traditions to develop “Haida manga.” While the artist is best known for his Haida manga artworks on paper, Levell documents how his “distinctive Haida manga aesthetic,” informed by an “unflinching” commitment to hybridity, extends to all the other diverse contexts in which he works.

Haida artist Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas explains, “I am committed to the idea of human hybridity as a good thing: difference is a fertile edge between ocean and river, a delta of possibilities” (p. 16). In Making Mischief: Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, Art and the Seriousness of Play, visual anthropologist Nicola Levell documents how Yahgulanaas’ art advances this positive view of hybridity. She explains, “Yahgulanaas is serious about the potential of hybridity, as an identification, aesthetic and strategy to elicit reaction and challenge established hierarchies, attitudes and stereotypes” (p. 8). Yahgulanaas mobilized this theme when he synthesized Haida two-dimensional design and Japanese graphic art traditions to develop “Haida manga.” While the artist is best known for his Haida manga artworks on paper, Levell documents how his “distinctive Haida manga aesthetic,” informed by an “unflinching” commitment to hybridity, extends to all the other diverse contexts in which he works.

Yahgulanaas’ complex concept of hybridity complicates Levell’s job as the author of Making Mischief. To do justice to the ideas animating Yahgulanaas’ philosophy, Levell must frequently remove the spotlight from him. Hybridity offers his “delta of possibilities” only when one celebrates and explores myriad relationships, connections and meanings potentially suggested by the art works. The art works allude to some of these complexities. Others spring from Levell’s own insights and perceptions, a participatory process consistent with the Haida-manga aesthetic. As Yahgulanaas states, “I encourage people to make observations and choices arising from their own experience without relying on the authority of the artist” (p. 10). Whether placed there by the artist or suggested by Levell, each of the relationships she highlights requires context that diverts the focus from Yahgulanaas.Each also demands explication in a succinct format that still conveys the complexities of the topic. Embracing that challenge, Levell shines. Again and again, she hits the sweet spot, eschewing reductionist treatments while resisting the temptation to lead us too far from Haida manga, the organizing principle that ties the text together. Just some of the excursions she offers include the history and influence of U-kiyo-e Japanese woodcut, recent initiatives by Haida artists to revise art historical vocabulary, “salvage anthropology,” historical remapping to change Indigenous names to English names, influence of Japanese art aesthetics on Western modern art traditions, responses of some Indigenous artists to Canadian settler art and the Group of Seven, participatory art and “relational aesthetics,” how Indigenous artists from Canada and elsewhere have recently employed cars symbolically in installations, the power of the Copper imagery in contemporary Indigenous activism in Canada, and Kandinsky’s formulation of visual art as music.

Consistent with Yugalanaas’ concept of hybridity, these excursions into relationships and context cite artists and writers from diverse cultures. Levell demonstrates both the feasibility and the importance of situating Indigenous artists within the hybrid contemporary circumstances in which they live. Yahgulanaas writes, “I don’t feel constrained by tradition rather I feel my learned techniques in North Pacific Indigenous art acted as a positive catalyst for the unexpected hybrid visual practice I explore today” (p. 136). Levell provides context: “In rejecting notions of cultural ‘purity’ and difference — ideas that have fuelled the Western discourse of authenticity that haunts Indigenous artists and their works — Yahgulanaas’ art effects a form of resistance. It seeks to fracture dominant Western systems of knowledge and representation to create an alternative space where a plurality of world views can coexist” (p. 42). Accordingly, Levell discusses his art in the broad, multi-faceted context that actually reflects lived experience.

Levell divides Making Mischief into five sections. The first provides a biographical overview, documents the beginnings of Yahgulanaas’ activism in his art, and traces his development of Haida-manga early in this century. In the subsequent chapters, she departs from a linear chronology focuses more on themes:: “Haida Goes Pop! Playing with Framelines,” “Cool Media: The Art of Telling Tales,” Culturally Modified: Precious Metals, Cars and Crests, and “Visual Jazz: The Adaptability of Forms.” The puns in Levell’s chapter titles allude to the puns Yahgulanass so often embeds in the titles of his art works. Not surprisingly, myriad interconnections resonate between chapters, and topics recur and overlap.

“Haida Goes Pop! Playing with Framelines” introduces Yagulanaas’ formulation of framelines, lines that flow continuously through his Haida manga graphics. The chapter opens with Yagulanaas’ words, “The comic form encourages me to extract meaning and form where I find it, in the Indigenous and the settler cultures, and to flip them upside down, reverse them, recombine them, to allow new meaning to emerge in renewed form” (p. 42). In his employment of lines in his art, Yahgulanaas chooses the concept of “frameline” as an alternative to the “formline” terminology art historians have long used to describe two-dimensional design in northern Northwest Coast Indigenous arts. This is a significant change. The “primary formline,” as art historians have used the term, refers to a principal boundary that defines the subject of the art work, and to which the other elements that comprise it are secondary. In contrast, as Levell explains, Yahgulanaas’ concept of the flowing frameline “does not necessarily dominate and contain the image content. It provides another liquid space where images can emerge, intervene and offer another perspective on the whole.” Levell calls the interior spaces created by the lines ‘the pockets in and around which action unfolds” (pp. 47-49). There, Yahgulanaas inserts imagery and action, connecting disparate imagery and vignettes and tying them together. The concept of framelines invokes dynamic processes of story-telling, relationships between the parts and the whole, and viewer participation.

These same concepts inform the rest of Levell’s book. Accordingly, the next chapter, “Cool Media: The Art of Telling Tales,” documents how Yahgulanaas uses the visual style of Haida-manga to break free of the linear sequential frames prevalent in Western comic conventions. Levell explains, “Yahgulanaas wanted to develop an alternative comic idiom that could accommodate the explosion of action and the multiplicity of play between physical and metaphysical beings and realms that are characteristic of Haida oral histories” (p. 67). In Yahgulanaas’ graphic novels, beings, scenes and landscapes converge from multiple angles, vantage points and perspectives. Describing The Last Voyage of the Black Ship (2002), the artist’s second manga, Levell writes “The manifold scenes erupt with action, motion-lines and movement” (p. 68). This graphic novel tells the story of how a girl, a bear and a supernatural being protected the old growth forests on Haida Gwaii from corporations intent on clear-cutting. It is fitting that Yahgulanaas relates this story, and his others, in a visual style that eschews the linear, uni-directional imperatives of Western comic book framing, the same reductionist, single-goal orientation that arguably underlies capitalistic systems.

Levell states that in developing Haida-manga, Yagulanaas sought to depict “the complexity of an alternative or more experiential worldview” (p. 67). A principal concept in his art, she suggests, is “afocalism,” a term introduced by art critic David Sylvester. In describing the later art works of Paul Klee, Sylvester observed, “These are pictures without a focal point. They cannot be seen by a static eye, for to look at the whole surface simultaneously, arranged about its center—or any other point which at first seems a possible focal point—is to encounter an attractive chaos” (p. 85). Instead, viewing is a dynamic, participatory process; the viewer must search the entire visual field to construct the relationships between the parts.

Afocalism demands experiential “seeing,” a constant awareness of the relationships between the parts and the whole that they form. This is actually how vision works. We walk around in the world seeing a broad field. We choose what to focus on in each moment, and we construct how the various components in that field of vision relate to each other to create a cohesive meaning. Yahgulanaas’ Haida-manga style reflects actual experience much more than the linear narratives prevalent in written texts or in Western comics.

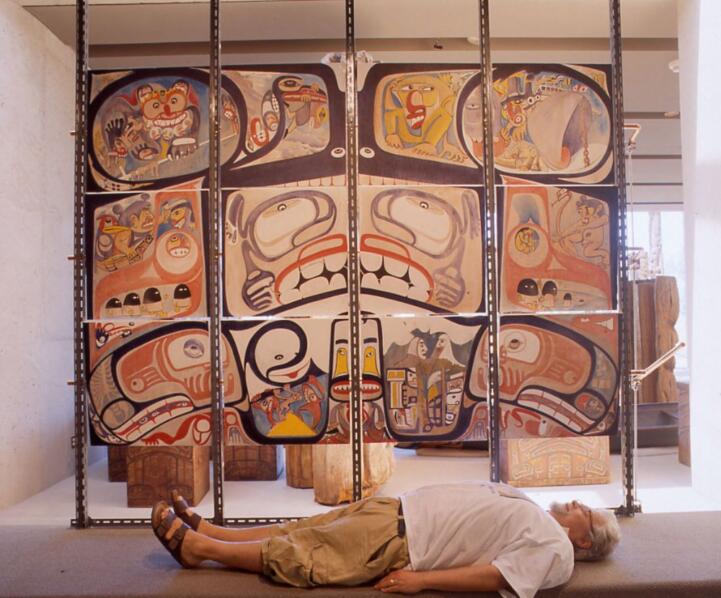

Of course, as the artist, Yahgulanaas provides the signposts. His organizing principle, the frameline, gives hints and clues as to how the diverse components make meaning together. In his watercolour Red (2008), each vignette stands on its own, yet through the framelines they connect to create a vibrant whole. The book form of Red comprises 108 individual pages that each present one frame of the watercolour. At the end, a two-page spread reproduces the entire watercolour, revealing how all the pages combine to create a “montage, with its variations of rhythmic lines, its play of perspective and focus and its proliferation of action that pulsate throughout….” (p. 90). Each page of the book becomes part of the whole, giving the other parts more meaning and taking meaning from them itself.

Each piece of Making Mischief does the same. The various and disparate excursions Levell presents–for context, to suggest connections with other artists, to introduce ideas of anthropologists, art critics and philosophers—embrace a form of “afocalism.” This is no conventional chronological biographical narrative about the trajectory of an artist’s achievements. Levell gives multiple points of entry, taking a non-linear path with many side trails to lookouts, inviting us to construct ourselves how they fit together and to launch from them into our own explorations. Levell uses the theme of Haida-manga as framelines: an organizing principle to tie together disparate parts and shake the potential “attractive chaos” into a coherent, deeply meaningful whole.

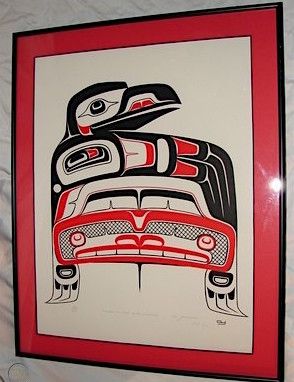

Based on individual interests, each reader may quibble with Levell’s choices. I did, but to me it feels like nitpicking. Levell implies that experimentation with “formlines” is a recent phenomenon. Could she have mentioned Haida artist Robert Davidson’s graphic design, or that of Kwakwaka’wakw artist Doug Cranmer, who both were experimenting in innovative ways decades ago? Yes, but she did not intend to offer a comprehensive history of such innovations. In the third chapter “Culturally Modified: Precious Metals, Cars and Crests,” she addresses Yugalanaas’ installations using car parts and explores his symbolism and those of recent Indigenous artists also working with cars. Could she have added more mischief by discussing Haida artist Don Yeoman’s 1979 silkscreen print Raven in the 20th Century,” in which he extends two-dimensional design to depict both Raven in and merged with a car? Yes, but this would lie outside her focus on installations that actually comprise car parts; her discussion of contemporary Indigenous artists from various places who recently have made such installations is great. The fourth and last chapter, “Visual Jazz: The Adaptability of Forms,” links music and art, but also bears the unjust burden of serving as a conclusion to the entire work. Could she have provided a more dedicated concluding chapter that more explicitly speaks to all five chapters? Yes, but the entire concept of a conclusion clashes with the afocal nature of her text. A more conventional conclusion marking the end of the work would not respect the non-linear underpinnings of Mischief Making, or of the Haida manga aesthetic.

It is easier to find weaknesses in the design and layout of the work. Many were probably unavoidable. Yugalanaas’ work invites viewers to construct meaning from the relationships between the parts and the whole. The book lacks the space to reproduce the whole in a size that shows all the components clearly, yet reproducing details of portions of the work isolates those sections from the whole. When feasible, readers should use a tablet or laptop to search online for the art works. Most are available somewhere on the Internet in a digital form that allows zooming in and out. Levell includes rich citations at the end of each chapter to well-known and lesser-known sources, but there is no bibliography. If one misses the first time a work appears in the footnotes, one must search back through previous notes to find the full citation. The book also lacks an index, which could help viewers create even more meaning from the non-linear discussion. For instance, an index could point to all the places in the text where Levell discusses punning and humour, or all the places where she explores use of framelines. Devoting space to a bibliography and index may have required cutting text or illustrations. Nothing that is included seems extraneous and so the trade-off was probably worth it, but it does come at a cost.

Those drawbacks in no way diminish the refreshing and vital achievements of the book. Lavishly illustrated and comprehensively researched, it demonstrates a non-linear, Haida manga-style approach to considering Yahgulanaas’ extraordinarily complex art work. Reading printed text is an inherently linear, solitary and passive activity, one very distant from the messages conveyed by the visual Haida manga aesthetic about which she writes. Levell rejects this discord between medium and message. She chooses a textual style equivalent to Yugalanaas’ visual rejection of Western linear comic framing. In taking readers on so many excursions, by showing how so many different topics converge, she may sometimes invoke figurative whiplash. Far from a fault, this is key to her success. Eschewing a simplistic linear frame, she invites readers to think actively themselves, to appreciate the fruitfulness of such excursions, and to launch their own explorations of seemingly different contexts based on their experiences and perspectives. From this multi-faceted, participatory experience, a delta of possibilities emerges.

*

A settler Canadian, Victoria Wyatt teaches in the Department of Art History & Visual Studies at the University of Victoria. Her courses explore creative responses of Indigenous artists to colonialism in North America from the eighteenth century to the present, with a focus on the Northwest Coast. She also teaches courses on Visual Studies. She encourages extensive analysis of the Internet as a resource for diverse voices and as a non-linear form of communication. In her research, she is interested in similarities between Indigenous Ways of Knowing and the recent paradigm shift in Western sciences that embraces processes and relationships within dynamic non-linear systems (e.g., neurobiology, quantum physics, epigenetics, climate science). She believes non-linear, holistic thinking that celebrates invisible interconnections is vital to addressing global challenges today. She holds a doctorate from Yale University and an honorary doctorate from Kenyon College, and is the 2020 recipient of UVic’s Harry Hickman Alumni Award for Excellence in Teaching and Educational Leadership. Editor’s note: Victoria Wyatt has also reviewed books by Alexander Dawkins and Martine J. Reid and for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster