1512 Aircrew of Bomber Command

Failed to Return: Canada’s Bomber Command Sacrifice in the Second World War

by Keith C. Ogilvie

Victoria: Heritage House, 2021

$26.95 / 9781772033816

Reviewed by Rod Szasz

*

RCAF Halifax bomber LL178 ploughed into the high Yorkshire moor disintegrating with its nine crew on a cold December night in 1944. Off course and in poor visibility LL178 with six Canadians and two British aircrew failed to clear the last hill before her descent into RAF Croft.

RCAF Halifax bomber LL178 ploughed into the high Yorkshire moor disintegrating with its nine crew on a cold December night in 1944. Off course and in poor visibility LL178 with six Canadians and two British aircrew failed to clear the last hill before her descent into RAF Croft.

They had just finished a “Gardening” operation, Royal Air Force code for dropping mines into enemy shipping lanes. This was not considered as high risk as deep penetration raids into Germany. Bombers over the sea were generally not as threatened by flak or enemy fighters as they were flying directly over German occupied territory. The mission completed and over friendly ground, the crew must have breathed a sigh of relief when making what they believed to be their final turn for landing approach.

Forty-one years after LL178’s crash, I was on the same high moor also lost on a hike in the early 1980s. With visibility down to thirty metres in mixed rain and snow, making my way via compass bearing I was trying to get off the high moor and into a good warm pub. Instead, I found LL178. A rough track of yellow withered grass and aluminum fragments poking through snow. A small memorial cairn, weather beaten, marked the dead.

Returning to London I checked the records at the Commonwealth War Graves. One of the pilots not only was a Canadian, but was from my hometown of Ladysmith, British Columbia.

Keith C. Ogilvie’s edited book Failed to Return: Canada’s Bomber Command Sacrifice is a collection of individual stories describing RCAF volunteers experiences in RAF Bomber Command’s war against Nazi Germany during the Second World War. The book describes Canadian involvement in the aerial battle over Europe in the Second World War. It is not the First World War tale of intrepid pilots, with throttles open in full acrobatic effect matching wits and derring-do with the enemy in aerial combat. Bomber Command’s war was calculated, measured, methodical and waged with increasing technological and impersonal ferocity.

Bomber Command’s pace was slow in the beginning years of 1939-1942. Planes not suited for strategically bombing Germany had abysmally low accuracy in hitting entire cities and high rates of loss from enemy action or accidents. Gradually science and technology bootstrapped by desperation lead to radar assisted navigation, advanced avionics and engineered airframes of the most technologically complex bomber of the Royal Air Force in the Second World War — the Avro Lancaster. Along with its harder working, yet less-well-known brother, the Halifax bomber, they carried unmatched loads of explosives and incendiaries and became increasingly deadly to anyone, civilian or military this load was dropped upon.

From 1943 to 1945 almost all German city centres were torched in mass incendiary raids killing thousands of civilians and aircrew. In 1943 Hamburg was burned out with 40,000 civilians killed in the aptly named Operation Gomorrah. By the end of the war destroying cities was what Bomber Command did best. In February 1945 Dresden was incinerated over three days with a similar number of victims. In this air war half-a-million German civilians died.

Bomber Command eventually needed 125,000 fully trained aircrew to bomb Nazi Germany into submission. Sixty thousand Bomber Command aircrew were lost on operations. Chances of eventually “getting the chop” (RAF slang for getting killed in combat) were about 45 per cent. In this carnage of flight operations over Germany, 10,000 Canadians lost their lives serving in Bomber Command’s Air War.

It was an enormous and costly campaign. Failed to Return is a collection of vignettes from mostly doomed RCAF members and includes a refreshing amount of information on their selection and training in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). This massive training effort was probably Canada’s greatest contribution towards the defeat of Nazi Germany in the Second World War.

If Britain surrendered, an Imperial redoubt would be needed to fight on: a place capable of taking pilots from all over the Commonwealth and training them over a vast geographic space. Next to the United States any buildup of British Empire forces in Canada guaranteed a good logistical supply of airframes for new pilots. In Canada training could be done far from the war zone. Crews could be trained and then funnelled into Bomber Command’s air war. By 1943 Bomber Command was sending out “Thousand Bomber Raids” against Germany in a single night. With the average bomber requiring seven crew, the need for trained crews was obvious.

The BCATP provided a fresh elixir of aircrews trained in Canada. Training facilities dotted the Canadian landscape. Schools for pilots of both bombers and fighters, navigation, air-gunnery, signals, and observation sprang up all over Canada. RAF personnel from the UK and pilots in RAAF and RNZAF, and the all-too-common US Volunteers in either the RAF or RCAF would find themselves training in Canada.

In the span of five years the BCATP turned out a total of 130,000 pilots and aircrew from all over the Commonwealth. The majority trained in Canada. Most went to crew the burgeoning Bomber Command Offensive on Germany led by Sir Arthur Harris (“Butcher Harris” — the name was coined ironically by the aircrews he commanded, not the enemy). If there was a debate whether Germany could be significantly weakened by aerial bombardment Harris was the man to test this theory.

Bomber Command lost, on average, about 3 per cent of their crews per raid. Some raids were thoroughly more nasty than others, with losses up to 10 per cent. Some may have been lucky enough to escape with no losses, though this was rare. A delicate balance of trained crews and newly minted bombers just barely kept up the offensive capabilities. After particularly disastrous raids in mid-1943 and early 1944, losses were so heavy that operations were scaled back until enough trained crews came on stream. Both the Lancaster and the Halifax needed a regular highly trained crew of seven. Planes could be replaced more easily than aircrew.

There is a myth that many air crew were rushed through and poorly trained. At best this is an exaggeration. Failed to Return includes biographies explaining training and personal motivation. Edward “Teddy” Blenkinsop of Victoria signed up in June 1940 and flew his first mission, dropping leaflets, in June 1943; Blenkinsop is shown on the book’s cover. Robert Urquhart joined January 1941 and went on his first operational mission in August 1942. Other training times were similar. It was the rare individual who participated on operations “ops” before a year of solid training.

Selection was rigorous with everyone expected to possess at least a high-school diploma. Those with maths skills were placed in navigation schools and learned how to plot dead reckoning to a target area. Flight Engineers were key to helping fly the aircraft concentrating on monitoring the various intricacies of pressures and fuel management as well as simple things like keeping throttles punched all the way forward during takeoff so that the pilot could solely concentrate on getting the unusually heavily laden bomber off the ground.

They learned to master an array of the latest technology man could devise to kill.

Very quickly navigation by dead reckoning using compass, map and protractor changed to using H2S radar and radio direction finding. “Fishpond,” a radar variant, allowed with some degree of accuracy bombers to see German night fighters before they saw them. Many was the crew saved by the urgent voice of the radar operator, “Fishpond contact, corkscrew right,” indicating a possible German night fighter setting up for attack. On command the pilot put the plane into a steep hard right dive converting altitude to air speed then left and then repeating. If successful, the night-fighter struggling to see would lose both visual and possibly radar contact with the bomber and the crew could chalk up a brief few second of intense fright and cold sweat. If unlucky the crew would receive a stream of large cannon shells through the aircraft shredding the interior of the plane, its crew and usually setting the aircraft on fire, ensuring a furious struggle by pilot and engineer to control the aircraft while crew tried, usually unsuccessfully, to don parachutes to jump out over enemy territory.

The odds were stacked against a standard RAF Bomber Command Crew.

Germany ramped up its own technology using radar-equipped fighters to find British bombers in the night. On the ground much of the guesswork was taken out of anti-aircraft defence when newly developed proximity-fused flak rounds picked up the magnetic signature of an aircraft and exploded nearby. It was a constant game of both side upping the technological and training ante until one fell from the sky.

Crews heading deep into Germany did not travel in large formations as often seen in American Hollywood movies. Commonwealth crews flew in what was known as a “stream” and arrived over the target at different times to bomb individually. They did all of this at night. It meant a lonely journey in darkness with the hum of engines, of blacked-out surfaces below and the nagging impression your ship could be ripped apart in the darkness without warning at any time. Failed to Return is full of accounts from lonely crews seeing explosions and fires in the distance, of lonely last radio contacts and then nothing. Crews watched large explosions or a burning plane in the distance going down over the blacked-out Reich, with nothing to be done but watch; plane and crew simply disappearing.

Ogilvie’s collection captures the pace and vibe of members strapping into each crew position. Using their parachutes for seat pads, and the standard banter, the check lists, flying sheathed in darkness from beginning to end to operations, and the almost hypnotic effect of engines in equal syncopation lulling the aircrew into an almost false sense of security. One also feels the break between routine and sheer terror. The fraction of a second gap between when everything is fine and when a crew is fighting for its life or simply ceasing to exist.

With night fighters attacking from below rear, with upward firing cannons raking the aircraft from one side to the other, crews often did not know what hit them. Aircrew usually did not wear parachutes because it made moving about in the claustrophobic aircraft awkward. If they had to bail out, an aircrew member might, with luck, get their chute on before leaving the aircraft. But this was rare. Only about 15 per cent of Avro Lancaster crews survived a shooting down, Halifax’s like LL178 suffered a higher plane loss rate but crew survivability was a little better partly because of the banal fact that the escape hatches were larger, a reminder that small differences in design can make a mortal difference.

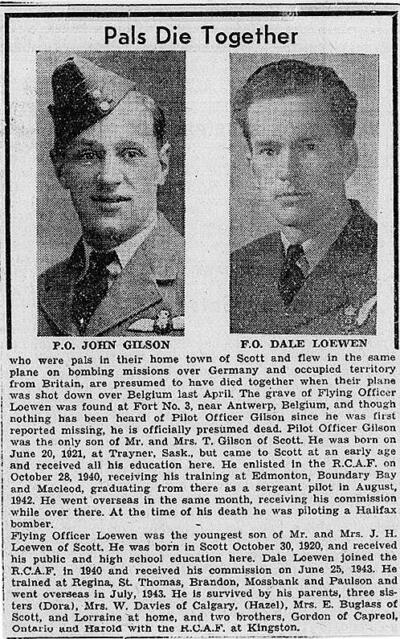

Ogilvie includes many photos of his subjects — striking pictures of the aircrew. Lanky prairie farm boys whose faces project uncaring happiness, or innocence and cultured naivety. Many facial expressions are far removed from the possibility of death; their eyes radiate confidence; fate does not hold them in their grasp. Expressions seem to will their own command of their future: confidence will see them through, until it doesn’t.

But there are also those who express pensive and indeterminate qualities, eyes averting the camera’s direct gaze. Who betray a fleeting lack of confidence to the camera, as if to say, “I think I know how this might end.” Some oblivious to fate, others exhibiting a sort of Thanatos-inspired acceptance.

A few centimetres in a certain direction can put a piece of shrapnel or a bullet onto a deathly vector where life and death were separated by mere fractions of an inch. No less in the case of the Halifax LL178 flying over unseen terrain. First a propeller caught the moor, then the bottom of the airframe. The aircraft heeled into the moor shredding itself and crew. “Another metre and the Halifax would have cleared” the very last hill before base, the crash report states. On the RAF Operations Board the Halifax would be marked, first, “Overdue” – after battle interrogation of other returning crews or search and rescue reports could generate new information clarifying the status of the aircraft. If no further information was heard there was the faint hope for families that their loved one had become a Prisoner of War. Planes listed as “Failed to Return” or “Crashed” on the Operations Board would be erased and new plane codes entered for the next operation.

Those crews “Got the Chop” in RAF parlance. Their lockers cleaned, personal affects gathered and sent back home and a new crew assigned to the bunks of those who did not return. All of this happened in as little as 8-11 hours. The jarring nature of being under fire, losing comrades, and then finding yourself back at base in a safe, warm operations room with bacon and eggs and all the coffee you could drink must have been one of the more psychologically jarring experiences in war. Those who survived suffered in later life. A few, very few, cracked or gave it up. Aircrew could opt out, but few did because their records would be officially listed, or rather tainted with the term “lacking moral fibre.” Whatever choice one took, it was tragedy all round. Although understanding of strain in combat had come a long way since the shell shock days of the First World War, Bomber Command did not embrace as wide an acceptance and definition of what we now call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

It is natural for countries to talk about its warriors, its airforce and its aircrew. To exalt them as unique or somehow exceptional (usually “better” than others). Whatever the merits or unexplained acceptance of such an analysis this is a myopic way to look at RAF Bomber Command’s war. It is as difficult to talk about a 100 per cent Canadian effort as a 100 per cent British effort. As politically incorrect as it is to celebrate Empire, Bomber Command was one of the most diverse organisations in a time where diversity was not a hollow celebration but a matter of life and death. Though Bomber Harris allowed the establishment of a nominal Canadian Group (the 6th) within Bomber Command, it would be inaccurate to look at this group as being in any way fundamentally different from any of the other groups in Bomber Command. RCAF, RAF and Australian (RAAF) and a host of other British Commonwealth nations mutually crewed each other’s planes and squadrons and many Canadians directly joined the RAF. It was a rare aircraft that was 100 per cent British or Canadian.

Personnel from all over the Empire, increasingly even those of visible minorities, were mixed with each other. The notorious “colour bar” was eventually lifted during the war and people of colour could, by the end of the war, command whites. Ogilvie and associate authors give a very good account of the international effort to include all crew members whatever their nationality, paying equal attention to all aircrews associated with the RCAF pilots. A typical crew wore the same uniform of an Empire at war. Outside of a shoulder flash with the single word “Canada” or “Australia” or New Zealand” or “British West Indies,” a lilt or accent, there was little making them different. It was not a New Jerusalem, but it was a far cry to what was happening in the deeply segregated US military.

And so it was with Halifax LL178 with her mixed crew.

Somewhere down in the east Yorkshire valley through the mist – according to the map — was a village with a warm pub, food and a conversant owner with a ready draught of ale. One last look at LL178 before descending through the fog into the valley. The ground rose just a little, and the grass parted revealing scrapes in the ground, clumps of grass still separated by bare earth. Here and there pieces of metal poked through the surface. Beside a bare patch of metal there was a single memorial. A large blurry block revealed writing. Upon it was simply scratched “RCAF 343 SQN. In Memory of the Crew of Halifax LL178.” Failed to Return.

*

Rod Szasz is an inventor and entrepreneur with a love for adventure and history. Educated at Malaspina University-College (now Vancouver Island University) and the London School of Economics, he has spent most of his adult life outside in the UK and Asia. When not busy hiking and climbing he maintains a website of self-translated Japanese war memoirs related to the war in Asia and the Pacific, 1931-1945. His translations and analysis have been used by international historians. Formerly a member of the International Institute of Strategic Studies and of the Royal Historical Society, he also teaches a class on Japanese foreign policy at the Elder College at Vancouver Island University. He lives with his family on central Vancouver Island, where he was born. Editor’s note: Rod Szasz has also reviewed books by Ben Nearingburg & Eric Coulthard and Brandon Pullan for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1512 Aircrew of Bomber Command”

An excellent piece of work and meaningful review. Great job! I’m reminded of another published Canadian book by Bob Middleton – Luck is 33 Eggs.