1474 Kinds of birth

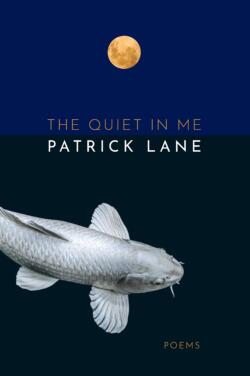

The Quiet in Me

by Patrick Lane, edited by Lorna Crozier

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2021

$18.95 / 9781550179811

Reviewed by gillian harding-russell

*

In The Quiet In Me, Patrick Lane writes from the perspective of old age with its inward vision of the paradoxes inherent in first and last events: of death in birth and the birth in death. In these spare poems that borrow metaphors from nature’s storehouse, the poet’s voice is alive and vibrant in his many incarnations that range from an association with the “mole” who “moves a small stone” “in his small room” and “waits out the rain” (“Carefully”), to the wolf spider that has excellent eyesight and hunts alone (“Little Wolf”). In the title poem “The Quiet in Me,” we see through the poet’s eyes as an old man in a wheelchair watching himself, fallen on the pavement, as in an out-of-body experience, and this scene provides a crux in the collection as a clairvoyant scene that implies what is lost and presages what is to come:

In The Quiet In Me, Patrick Lane writes from the perspective of old age with its inward vision of the paradoxes inherent in first and last events: of death in birth and the birth in death. In these spare poems that borrow metaphors from nature’s storehouse, the poet’s voice is alive and vibrant in his many incarnations that range from an association with the “mole” who “moves a small stone” “in his small room” and “waits out the rain” (“Carefully”), to the wolf spider that has excellent eyesight and hunts alone (“Little Wolf”). In the title poem “The Quiet in Me,” we see through the poet’s eyes as an old man in a wheelchair watching himself, fallen on the pavement, as in an out-of-body experience, and this scene provides a crux in the collection as a clairvoyant scene that implies what is lost and presages what is to come:

There is a quiet in me: the old man I lifted today from the pavement, his

weight beyond being,

his legs useless, his wheelchair a step away, and he was like some warrior fallen

from his horse, his tank, his life (p. 40).

From the “warrior,” “his muscled arms in me,” the speaker moves to a crippled bird image, “his leg, more like the empty wings of a bird just dead.” In this tableau that resonates with life and metaphor, both epic and from the natural world, I found myself envisioning the struggle of Laocoon with the sea serpents. Like Laocoon who cannot reverse fate even as those onshore helplessly watch it unravel, so too the speaker in the poem finds himself, with epic heroism and the pathos of old age and its frailty, hopelessly resigned to his situation.

That death is tied up with life and that the living remain bound to the dead is deftly expressed in “Small Elegy” when the speaker remarks: “The silence of the dead is what we own,” and “It’s why we sing.” Less expected is the projection that the dead might also rely on the living to forward their memory:

Go on, I hear my father say, my mother too,

and though they rest in sunken graves

I hear them still (p. 24).

That the dead “sing” “in the rubble and in the fires,” and that the living must listen to the dead to uncover meaning about themselves becomes the driving force in this poem: “Their burden is our lives,” and “We pray since we cannot turn away” from where we have come and what we have become.

As well as death, love and birth are woven into the weave that is life. In the poem “A Christmas Poem,” the speaker describes his experience in helping to deliver a woman’s baby in a remote northern place and endows the poem with echoes of the Christmas story. It is indeed a lovely poem in its incremental building up of the biblical setting as applied to this northern locale. In response to a request for a “Christmas poem,” the speaker remarks, “you mean, something/ about birth and death” and “something/ about stables and animals” “with the soft smell/of cattle in winter” (p. 16). Here in this poem of tenderness accentuated by pain and followed by redemption as the baby is passed to his mother’s arms, Lane is at his best: “with something in her face you didn’t understand” and “the quiet in her after such a birth” (p. 17). The word “quiet” from the title echoes through the collection in gathering contexts to become a motif and reminder about a quietus or inner peace that The Quiet In Me is all about.

A triadic cluster of love poems that feature love from the perspective of the womb, a coming-of-age sexual desire and empathetic love associated with maturity appear in “Lacrimae,” “Love, Too” and “Morning.” In “Lacrimae” with its Latin titular association of “tears” with the salt or amniotic waters inside the womb, the speaker presents a tableau of himself as an embryo watching out from the underwater of the womb: “What wonder it was to swim inside her, / hear the drum song beating” (p. 32). Another side of love in “Love, Too,” the speaker evokes the longing of sexual desire:

A broken sky and want, light almost gone,

the meteors born out of what blood, falling upon your eyes; the woman

who rises in the dark, her hair tumbling, and does not return (p. 33).

With quick, impressionistic strokes, the movements in the scene unfold in the manner of the hunter Actaeon’s illicit sighting of Diana, naked and bathing. With the speaker’s love unrequited, at least within the confines of this poem, desire reaches a crescendo and the poem ends on this high note.

Another kind of love rooted in Keats’ negative capability and suggestive of empathy enters “Morning,” dedicated to Lorna Crozier, his wife and posthumous editor as well as perhaps the subject of the Diana figure from the previous poem. Here nature in an implicit unfolding flower metaphor with “stem and root” is associated with a woman’s “foot, ankle, breast and belly,” and that woman, like the Diana figure from the previous poem, cares for all the animals: “in her hands are many hands, paw, and fin,/ wing and wonder”:

Her blood flows with the hearts of the many,

the risen in her clenched fists, the fallen in her open palms (p. 34).

While “the risen” in her “clenched fist” evokes resurrection, “the fallen in her open palms” suggests those that have dropped dead. Although Diana is a huntress, she is also a protector of the animals and under her stewardship animals are both birthed and cared for, with death necessary to curtail an overabundance of animals that would lead to starvation.

Another face of desire in association with death surfaces in “How Many Times Have I Taken Out My Death.” In a psychological landscape that can also be found on a physical map, the speaker considers whether he was ever able “to see the stars” “above the stink of False Creek” when he attempted to drown himself “over and over.” As in “Love, Too,” where love is unrequited, here desire for death is unsatisfied. Further entangling the rites of existence, death by drowning is seen as “an older birth”:

Death, you sullen master, come

find me in the waters of my birth (p. 55).

“Don’t let me /live so long that I call you friend,” and “follow you, as a dog does, servile, whining” the speaker exhorts “Death” (p. 55). Effortlessly, Lane introduces birth imagery into this sublimated death scene using concrete images from our world with beauty and precision. Again, in “OM,” the speaker wrestles with the idea of death, once more evoking the mole in “Carefully” who moves a stone futilely in the manner of a Sisyphus while it continues to rain. On being served coffee, the speaker accepts “the smile of my woman” but feels as fragile as “winter grass,” even as he remembers “when we moved/ naked in the summer far away.” With self-irony, the speaker chastises himself as a prince who has set out on a journey “to discover suffering.” “Ah, thinking won’t get me there either,” he chides himself (p. 53). In cruel kindness – a cruelty unknown to the animal who thinks it is giving a gift – the cat makes a present of a “headless mole,” with its fur “the colour of the moon”: death, at this juncture, must be considered a gift.

In The Quiet In Me, Lorna Crozier has assembled a beautiful collection of poems whose themes flash with moments of love and pain, beauty and despair that are after all the threads in the fabric of what is life. There are many poems that are truly gems in this slender and lovely book with just under 60 pages. Also, I love the ‘quiet’ of the cover design by Rhonda Ganz, with the white of a large or fleshy fish – not a whale but perhaps a ground-feeder or carp in False Creek? – under dark waters and a far-off gold moon. This book is a keeper.

*

gillian harding-russell is poet, editor, and reviewer. She has five poetry books published, most recently Uninterrupted (Ekstasis Editions, 2020) and In Another Air (Radiant 2018), both shortlisted for Saskatchewan Book Awards. Also, she has six chapbooks published, the latest Megrim (The Alfred Gustav Press, 2021). Her work has been anthologized in eighteen poetry collections and published in journals across Canada. She received a Ph.D. from the University of Saskatchewan, completing her dissertation on postmodern Canadian poetry. Editor’s note: gillian harding-russell has also reviewed a book by Yvonne Blomer for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1474 Kinds of birth”