1427 An artistic and spiritual journey

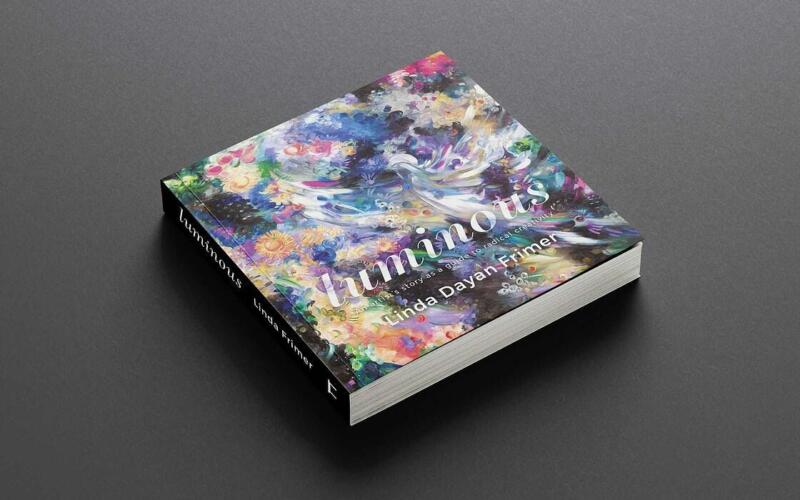

Luminous: An Artist’s Guide to Radical Creativity

by Linda Frimer

Vancouver: Granville Island Publishing, 2022

$39.95 / 9781989467220

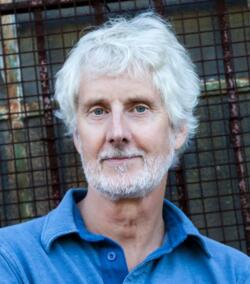

Reviewed by Michael Kluckner

*

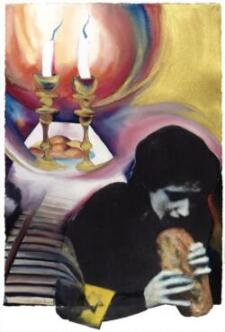

Linda Frimer’s Luminous is a complex and intriguing work that mixes memoir, spiritualism, and meditations on art and colour with reflections on Judaism and her own family’s roots through generations going back to Romania. It spans the seven-and-a-half decades of her own life — a sort of ‘coming of age’ both as a person and an artist.

Linda Frimer’s Luminous is a complex and intriguing work that mixes memoir, spiritualism, and meditations on art and colour with reflections on Judaism and her own family’s roots through generations going back to Romania. It spans the seven-and-a-half decades of her own life — a sort of ‘coming of age’ both as a person and an artist.

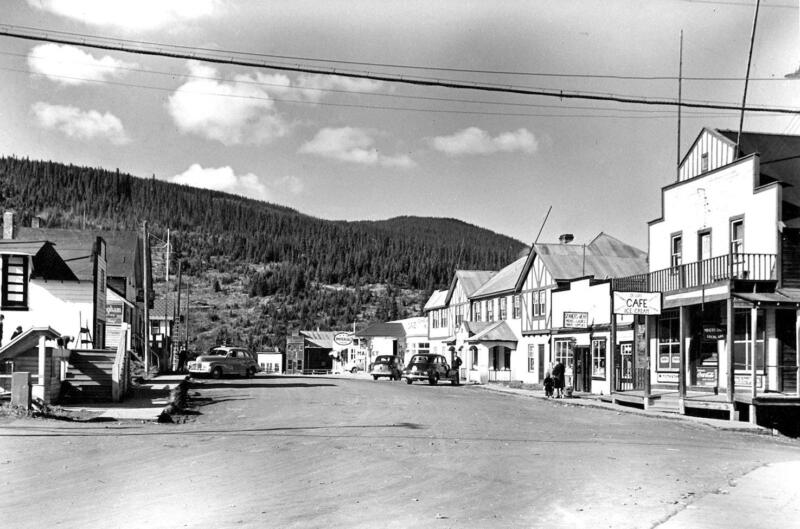

Born in the Cariboo gold-mining town of Wells in 1947, Frimer is the daughter of a Jewish couple, Jack and Annie Spaner, who moved there after her father’s service in the Second World War. Why Wells? Its prosperity attracted a permanent population — it largely missed the Great Depression owing to its active gold mine — and Spaner’s Men’s Wear on Pooley Street became the family business. Her narrative traces the lives of her grandparents, immigrants who settled on the Canadian prairies and were merchants trading with Indigenous people in Alberta and B.C. Historic photos of her ancestors, or places like Barkerville in the BC Interior near her own birthplace in Wells, feature on some pages.

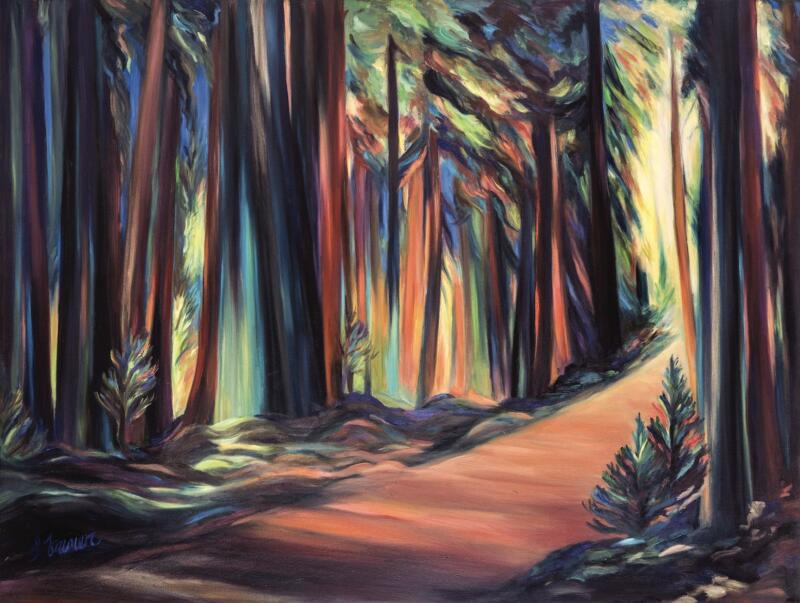

The book’s chapters explore the meaning of colour used by historical artists in paintings that are referenced but not illustrated, presumably because they can be found with a click or two on the Internet. The book’s images are her own, painted in the luminous colours of her book’s title, together with more mysterious illuminations or ruminations on Jewish mysticism, reviving my distant memory of studying Marc Chagall, the essential Russian Jewish artist, at university. She also reflects on First Nations beliefs, drawing respectfully on a symbol of her Indigenous neighbours in the Cariboo in watercolours such as The Raven’s Knowing (p. 27), “the connector between earthly dwelling and the spiritual realm,” and comparing it with the eagle which has “the closest relationship with the creator” in both Jewish and Indigenous stories.

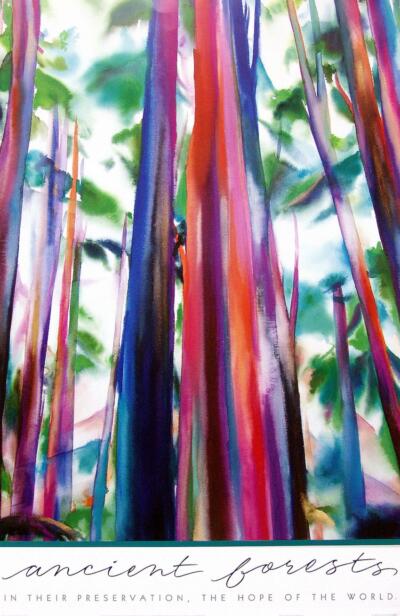

One subject that unites her work is trees and their healing ability. Some paintings beg comparison with Emily Carr’s famous forests, but Frimer’s light-filled spaces and Post-Impressionist/Fauvist palette will hit a stronger emotional chord with many people. She uses acrylics, oils and watercolours, and collages photographs into mixed-media canvases. Some of her paintings are quite representational, others almost abstract, while still others explore mystic images and juxtapositions.

A notable aspect of the book is the words of advice to aspiring artists and spiritual seekers that are announced on the page with a graceful, simple outline of a dove. Beside it is a lesson, sometimes an aphorism, such as “Starting from a dot, draw shapes on paper using colour art chalk like the first Paleolithic artists and like Renaissance artist Michaelangelo did. Feel the soft impact as the chalk presses into your paper and notice how it creates dusty blurred edges” (p. 36).

Another, two pages later: “Use colour straight from the tube, without mixing, and apply it in short thick strokes like Vincent Van Gogh did.” She follows this with a quote from that artist: “What would life be if we had no courage to attempt anything.” Later, she quotes Twyla Tharp: “Art is the only way to run away without leaving home” (p. 147).

These lessons and quotations come to the reader almost randomly, just at the point when her intense meditations on her life and the history of art — on European and North American painters, how they used colour and what the colours meant to them and their culture — make you want to pause and absorb, perhaps re-read. There are pages on colours themselves, illustrated with details from her paintings, and brief descriptions such as “White was clouds, snow, teeth, the moon, a nursing mother’s milk, chalk, bone and …” (p. 32). Her palette changes as she explores the Holocaust (p. 200), finding in yellow both the joy of sunlight and the memory of the colour’s use to identify and oppress Jewish people in the Nazi era.

Linda Frimer gained recognition for her work and exhibited alongside artists including Raymond Chow. She became well known for paintings she donated to help the Western Canada Wilderness Committee, when her art took an explicitly environmental turn. Other environmental organizations, such as the Trans-Canada Trail and the Raincoast Environmental Conservation Foundations, have used her pictures. She donated paintings to support women’s and health causes (p. 272). She worked with Cree artist George Littlechild on a set of shared portraits, including one of their grandmothers. Her artistic and cultural efforts were recognized by an honorary doctorate from the University of the Fraser Valley in 2016.

Her travels have animated both her life and art, including a trip to her great-grandmother’s hometown in Lithuania. At the end of the book, she returns to visit Wells and quotes Lawren Harris that art is “a high training of the soul, essential to the soul’s growth, to its unfoldment” (p. 259). In the epilogue, she describes a trip with fellow artists to Haida Gwaii and the richness of its Indigenous memory.

Spiritual reflections on life, such as the one imagining the months between her conception and birth, reflect her personality. She writes in the first person: “I am water … It cleanses and purifies, and as the energy of the unconscious, relates to the expansion of dreams and pleasure…” She then addresses the reader: “Imagine your entire body as fluid, transparent water” (p. 89). The transitions from a memory to a reverie on colour to a mini-biography of an artist can be jarring at first, but the reader can quickly get used to her style.

The book will appeal to fans of Frimer’s paintings, of course, as well as to people on an artistic or spiritual quest who will find in her a kindred spirit. Reading it is like listening to a rather discursive but interesting and erudite conversation. In fact, the reader is invited to join in, to tear a piece of paper and examine it, to paint a brushstroke, to put two marks of different colours side by side. Although it is her journey, we are urged to have one as well.

At the end she leaves the reader with a heartfelt personal statement of artistic advice and ideals:

Artists, as our known convictions dissolve into another chance, let’s fill our palettes with luminous colour. And while painting the often intangible yet imaginable in the world, let’s not forget that each moment is an opportunity to experience the wonder of creation. Let’s remember to play like a child, to get lost and find more of ourselves in the process, to fail but never stop trying, to have integrity in all our actions and to always be boldly grateful and kind. Strengthen the intention to shine brighter, to love more completely and to bring something new into each day. Let’s return to our essence more often and dissolve differences where we can, with the intention to create our stories into one unified work of art.

*

Michael Kluckner is a writer and artist known for his 1990 book Vanishing Vancouver and its 2012 sequel, Vanishing Vancouver: The Last 25 Years (both Whitecap Books). He was the founding president of Heritage Vancouver, chaired the Heritage Canada Foundation, and is past president of the Vancouver Historical Society. He lives with his wife Christine Allen near Commercial Drive in Vancouver. Editor’s note: Michael Kluckner’s more recent books include Here & Gone: Artwork of Vancouver & Beyond (Midtown Press, 2020), reviewed by Martin Segger; Toshiko, (Midtown, 2015; 2020), reviewed by Phyllis Reeve; Julia (Midtown, 2018), reviewed by Yvonne Van Ruskenveld. He also provided illustrations for The Reporter and the Winnipeg General Strike (Granville Island Publishing, 2020), reviewed by Ron Verzuh; and Lowering Simon Fraser (Contemporary Art Gallery, 2019), reviewed by Forrest Pass. His most recent book is a graphic novel, The Rooming House (Midtown, March 2022). Michael Kluckner has reviewed books by Ellen Schwartz, Ellen van Eijnsbergen & Jennifer Cane, Terry Watada, Larry Beasley, Kevin Chong, and Sean Karemaker, and he also reviewed Lost Vancouver: an Unexpected Art Deco Tour for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1427 An artistic and spiritual journey”

Linda is inspirational and a credit to her Cariboo northern BC beginnings, and her Chagal like influences and Judaic roots. We are proud of Linda as a people. Full of love and generosity and affinity to nature and Indigenous people. Another daughter to Rachel and Moshe Ben-Ron.