1339 When belonging goes bad

Among Silent Echoes: A Memoir of Trauma and Resilience

by Phyllis Dyson

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2021

$24.95 / 9781773860640

Reviewed by Lee Reid

*

“My mother had needed help, not bullets” (p. 21). With Phyllis Dyson’s book, Among Silent Echoes, it is not immediately evident why Phyllis, at age 45, decides to explore the brutal death and painful life of her schizophrenic mother. In 2015, she was the same age as when her mother died in 1990. Is digging into the past a prescribed rite-of-passage for one’s mid-years, when aging exacerbates the hunger for identity and the buried pain from unresolved traumas? Or is this book written as a beacon to encourage people to search for the lost parent they never knew?

“My mother had needed help, not bullets” (p. 21). With Phyllis Dyson’s book, Among Silent Echoes, it is not immediately evident why Phyllis, at age 45, decides to explore the brutal death and painful life of her schizophrenic mother. In 2015, she was the same age as when her mother died in 1990. Is digging into the past a prescribed rite-of-passage for one’s mid-years, when aging exacerbates the hunger for identity and the buried pain from unresolved traumas? Or is this book written as a beacon to encourage people to search for the lost parent they never knew?

For many people in mid-life and old age, there comes a mysterious ripening time when you know you must exhume the family skeletons. A time to explore your sense of identity by combing through family albums and mementoes; a time to reach out, ask questions and connect with family members, be they alive or dead or disappeared. You might find yourself writing letters to, and for, people you have never met. In fact, this process, memoir-making, is possibly transformative. The letters might grow into books like Phyllis Dyson’s Among Silent Echoes. Writing and sharing your memoirs, or going into therapy, or interviewing family, or searching one’s ancestry, or recording one’s nightly dreams… all represent the many effective ways to begin a quest for healing. This is where legacy, and where creative expression, begins.

I have no doubt that Among Silent Echoes may well be a healing story for readers, as well as a legacy for the author. In the least, the book might catalyse curiosity in readers to begin their own quest – a quest to restore family and to clear up the lies and misconceptions that abound when families do not communicate, or when they hide the truth. If readers begin with the assumption that most families do hide a truth, especially regarding long-buried traumas or oppression, then what you discover may be liberating.

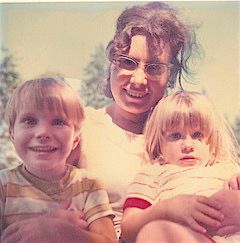

For Phyllis Dyson, the quest began in 2015 with her ten-year-old daughter’s curious questions about her grandmother. Years before, Phyllis had resolved to bury her family history and move ahead in life. She was 20 when her mother died in 1990. Since then, Phyllis and her brother faced forward, determined to place the past behind them. Eventually, and catalyzed by her young daughter’s probing, her past caught up with her. As the ghostly echoes of memory spoke out, and despite years of family silence and suppression, Phyllis wrote their stories, thus bringing her dead mother Carol Anne back to life.

Written in a reflective honest narrative, Phyllis’s story gently layers fragments of childhood memory with occasional reports about her mother and their family from the adult world of social workers, psychiatrists, and mental health clinicians. Reading her book is not at all dry or burdened with the cold analyses of the social systems that policed her family. This quietly nostalgic book is more comparable to savouring the subtleties of a Monet painting or a fine vintage wine. The flavour grows on you. Carefully and gently, Dyson paints a picture of the silence that hides her mother’s existence, an existence filled with anguish, for example:

All these years later, I have learned that it was those many weeks without medications that caused the delusions and hallucinations of paranoid schizophrenia to wreak havoc in our mother’s brain…. But, as far as I can tell from reading her records, not one mental health professional had kept our vulnerable little family on the radar during that entire time (p. 63).

The book begins with the children, a very young Phyllis and her slightly older brother Ron, living in Burnaby with their mother Carol Anne. Carol Anne is impoverished, ditched by her alcoholic husband who is Phyllis’s father — or maybe she kicked him out. She lives alone with the children, except when she brings the occasional man or relative home, and has been hospitalised many times for schizophrenia, with self-harming behaviours or suicidal tendencies. Normally terrified of men, Carol Anne carries a knife to protect herself. After all, whenever she is hospitalised, it is men who arrest her or who convey her to hospital. The picture that readers get is of a woman struggling to value her kids and to be valued and respected for herself, but who is continually marginalised because of her poverty, gender, eccentric behaviours, and her mental illness. This is a mother who was never taught the skills to cope with her external and internal realities.

How then, one might ask, did young Phyllis stay sane? Throughout the book, we get the impression of a suppressed and lonely girl who learned to survive by taking care of others. A child who was responsible and hard-working, despite being continually shamed by her caregivers in a series of temporary homes. At times, her grandmother mysteriously appears to set things right, and then disappears back to Ontario. The children do not realise that their grandmother surfaces at crisis times when their mother is unstable, and that she attempts to negotiate on behalf of Carol Anne and her children with the authorities.

Initially, the children were placed in foster care during one of Carol Anne’s breakdowns. They were allowed to visit their mother for a couple of hours every other weekend. At the time, Phyllis was 9. “When each visit came to an end, I would have a lump in my throat and my eyes would start to swim but eventually I came to accept the way things were,” she writes (p. 89). Although the children’s lives were often turned upside down, the mental health system and social workers never explained to them what was happening. What they did give Phyllis was a diary of sorts called “Watch Me Grow.” There, she chronicled meaningful events and her growth through her childhood. This diary became a treasured record of scanty information she gleaned about her family-of-origin, usually by asking questions like her own daughter did. For example, into her diary she tucked her award for first class honours from the Royal Conservatory of Music, which she won in her teens. When she learned that her father had also been musically gifted, she wrote it down. And so the diary grew into a source of identity and belonging. I wonder if this diary became the seed for Among Silent Echoes, which Phyllis wrote many years later?

As wards of the court, Phyllis and her brother were eventually fostered out to questionably more functional relatives who used the extra government child payments for anything but child welfare. Phyllis was put to work by her relatives and loaded with child care duties and housework. “Can’t you see they’re using you?” comments a friend about the new “family.” Desperate for any kind of family, this odd household of neglectful imbibing adults and their younger children became Phyllis’s responsibility. Her uncle then moved Phyllis and her brother away from their mother’s city with his menagerie to a dreary series of shacks in the Cariboo, as Phyllis writes: “At that moment I felt a change, an indescribable feeling deep within my soul. It didn’t matter how I felt. It didn’t matter what I said. I had no control. Not even Mom could help” (p. 95).

When nine-year-old Phyllis and her brother were removed from the home by social workers, she recalled her mother saying, “I’m not going to live long anyway, so what the hell….Well, I guess that’s it then, kids … I don’t know when I’m going to see you again. Maybe never. Looks like you don’t need me anymore. I might as well move back to Ottawa” (p. 81). At the time, Phyllis was too young to recognise the despair and sacrifice that losing her children meant for her mother.

After this, Phyllis and her brother could only reach their mother by train, commuting to Burnaby and later to New Westminster for week-long visits twice a year: winter and summer. What the children did not know was that their mother would skip meals and save money in order to treat her kids with good food and gifts whenever they came for visits: “It bothers me now that we didn’t exchange phone calls or visits between visits. It seemed like my life was like the train we travelled in: I stepped out of one compartment of my life into another” (p. 143).

Among Silent Echoes provides disturbing clues about her mother’s hard life. Carol Anne was verbally if not physically abused by her angry and distant father — Phyllis’s grandfather – who was a war veteran. Her young brain was affected by childhood encephalitis. Carol Anne was raped by another teen at age 13, after which she carried a knife for protection. She became paranoid about men. As a pregnant young woman her parents pressured Carol Anne to abort Phyllis. She refused (p. 151). Following the onset of psychosis when she was 15, Carol Anne was committed by her parents at 16 to a psychiatric hospital. Periodically, she was treated with electroshock therapy whether or not she wanted it (p. 145). Later in life, as a mentally ill woman, she was targeted by landlords to be evicted or mistreated. She was expected to show up at a clinic bi-weekly to receive medication by injections. The medication controlled her delusions and hallucinations. When Carol Anne went off her medications, she could get violent or suicidal, and she was vulnerable to exploitation.

Phyllis Dyson treats her mother’s character with sympathy and compassion, despite the chaos and broken attachments her mother caused her children. With every unusual outburst, withdrawal, and with her mother’s many regressions in behaviour, what we have are the musings and longing of a daughter who asks, “Who was my real mother? Who was I? Who am I now? How can I determine my own life?”

This is not a violent book. Heart-rendering at times, it might emotionally trigger a few readers. It is a tender book of memories collated to make sense of Phyllis’s lonely and painful childhood through to early adult years. In tandem, she patches together the puzzle pieces of her mother’s identity at similar stages and ages, which is not easy because Carol Anne was an absentee mother with a condition that would cause shame and rejection in many families.

Ironically, Phyllis as a child called her mother the “fun parent.” By this, she meant the parent who was not burdened with the day-to-day responsibilities of childrearing, a job that consumed young Phyllis’s life. Whenever her mother had Phyllis and Ron visit, she could focus on creating fun for them. There were many outings to Deer Lake, to Playland, or to Stanley Park. As Phyllis shares years and vignettes of growing up with and without Carol Anne, it gradually dawns on the reader that this “fun” must have been very difficult or emotionally wrenching for everyone.

One wonders how Phyllis retained her stability? Perhaps this will be the subject of another book. Readers will experience her as a character who provides sensibility and coherent care to people around her. In a book otherwise populated by mostly exploitive or disinterested adults, she is able to conjure sanity. The relational themes in Among Silent Echoes feature intimacy and distance, survival strategies and cover-up secrets in families. Through pithy interactions and dialogue, and with astute character descriptions, Phyllis is adept at contrasting love with dysfunction and exposing the neglect of children through poor parenting and the abuse of their vulnerability by adults.

At the core of the book is the impact of child abuse on a family and how this trauma conveys through future generations only to surface as anxiety or depression or PTSD, and in a legacy of dysfunctional relationships, addictions, or suicide.

On a larger scale, what Dyson really addresses is the oppression and abandonment of mentally ill people. Although the children were abandoned too, on the surface their needs appeared to be taken care of. They were fed and sheltered but they were emotionally neglected or exploited. What was worse? An incapable mother who loved her, or an indifferent family who sheltered her? “Like my mother, I was torn. Part of me wanted to go back to her, and part of me didn’t” (p. 81). Many children never show underlying trauma; it may be masked by stoicism, by pleasing behaviours attached to the caretaker role, by violence, or by withdrawal into a private world of fantasy.

As a teenager, Phyllis found solace and creativity in music. She learned to play the flute with a married couple, teachers of a sort, who took her under their wing. Sadly, that too was threaded with sexual abuse. Yet her writing reveals the sense of innocence and loyalty that children maintain, despite horrific betrayal by adults.

How and why did Phyllis’s mother die? In 1990, Phyllis, aged 20, was attending Capilano College and subsisting with her brother in West Vancouver on a shoestring budget. Her mother was shot to death by police at a SkyTrain station in New Westminster. Hearing of this tragedy, Phyllis’s ten-year-old daughter comments, “That’s really sad, mum….” (p. 17). Carol Ann was shot for brandishing a knife at police during a psychotic episode when she was off her medications. Until then, the social welfare systems had ignored the warning signs and young Phyllis’s pleas for help as she noticed her mother’s deterioration.

Carol Anne’s demise is not surprising in this sad yet surprisingly hopeful book. Phyllis Dyson writes elegantly about the understated heroism of victims like her mother and of their children and, in doing so, teaches readers to be understanding and compassionate toward mental illness. Among Silent Echoes will inspire hope in readers: hope that good people like Phyllis can survive and grow, particularly when belonging goes bad. It reveals the hidden ways a mentally ill parent like her mother will try to protect their children. “Mom never drank alcohol. I realize now that she knew it could react negatively with her medication” (p. 83).

Among Silent Echoes is also a very moving book about posthumous reconciliation and redemption between a mother and daughter. By 2015, Phyllis was a schoolteacher who also taught music. She was married with a young family and a full life on the Sunshine coast. Coincidentally, she was motivated to interview relatives and clinicians in the social systems. She wanted to know the forces that shaped her life. Among Silent Echoes chronicles the people who did support young Phyllis’s creativity, her musicality, and her intelligence… and who cared about her despite some questionable ethics. Thus we learn how important to a child’s stability are a few good people, empathic neighbours, a grandparent or two, and sensitive teachers.

Trauma therapists would not be surprised at the coincidence in age between mother Carol Anne’s death and daughter Phyllis’s book. Traumatic memory often rises to the surface with triggers such as memorials and anniversaries or, ironically, when life offers more safety or security. The memoir process, reflected in this book’s genre, often does commence later in life, as it did with Phyllis when she was 45. When she realises why her mother sacrificed her children, she reflects: “Looking back, I think our mother was like the women from developing countries I’d read about … who give up their children so they have a chance at a better life” (p. 87).

Today, Phyllis Dyson is a member of the BC Schizophrenia Society. This society has developed a personalised advance care plan for people challenged with mental illness. It is called the “Ulysses Agreement,” a mechanism that invites families to collaborate and plan safety measures with the patient while they are stable. In doing so, families and children gain a transparency and a safety net should their loved one become ill. During Carol Anne’s life, this was not available. We will never know if it could have saved her life and her family. “As a result, my mother got sicker,” Phyllis reflects, “so that at last the symptoms that had been slowly hijacking her thinking pulled her feet from under her and caused her to stumble on the cracks within a faulty system where all that there was to catch her were bullets” (p. 195).

*

Lee Reid is a retired clinician from Nelson Mental Health. She is also author of three books about the resilience of BC rural and coastal communities. Recently, she has written and self-published a fourth book about the multicultural workers and residents who populated an historic extended care hospital in Nelson: Stories of Mount Saint Francis Hospital: 1950-2005, which illustrates a legacy of compassionate nursing care. She has also written articles and reviews featuring intergenerational education, rural home support care services, and the health challenges faced by rural BC seniors. Her previous books are From a Coastal Kitchen (Hancock House, 1980); Growing Home: The Legacy of Kootenay Elders (Nelson, 2016), reviewed by Duff Sutherland, and Growing Together: Conversations with Seniors and Youth (Nelson, 2018), reviewed by Luanne Armstrong. Editor’s note: Lee Reid has also reviewed books by Joan Neehall, Janie Brown, June Hutton & Tony Wanless, Megan J. Davies & Rachel Barken, Ellen Burt, and Luanne Armstrong for The Ormsby Review. In 2018 she contributed a popular memoir of growing up in North Saanich, The Spider Hunters. Visit her website.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1339 When belonging goes bad”