1328 Money talks on the Belt and Road

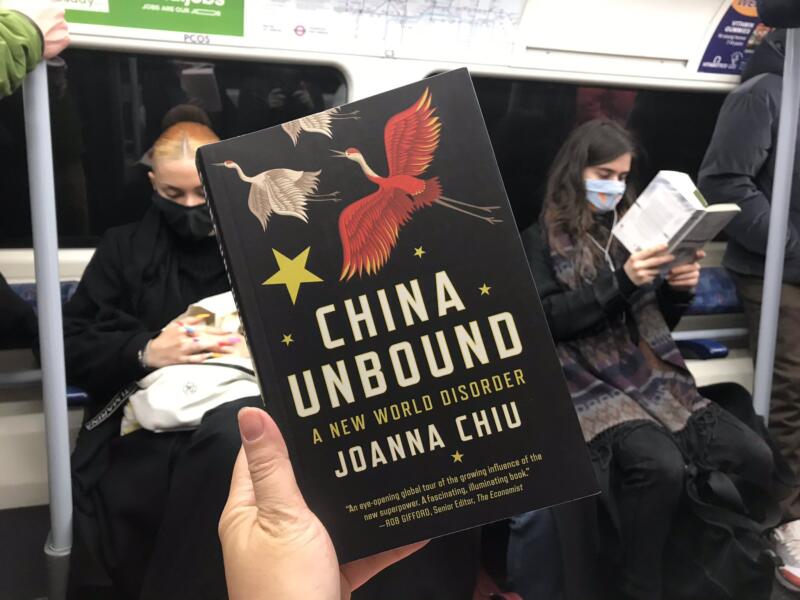

China Unbound: A New World Disorder

by Joanna Chiu

Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 2021

$24.99 / 9781487007676

Reviewed by May Q Wong

*

What do we really know about China? For centuries, it was a kingdom unto itself, sealed off by choice to the outside world, shrouded in mystery. For over a century, invaders cracked it open and carved out bits and pieces until a revolution enabled it to regain control of its sovereignty, and its borders were closed once again. When its doors opened again, China did so on its own terms. The mystery of China remains because the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) keeps tight control of information. How did China become the powerhouse it is now? Why should the world pay more attention?

What do we really know about China? For centuries, it was a kingdom unto itself, sealed off by choice to the outside world, shrouded in mystery. For over a century, invaders cracked it open and carved out bits and pieces until a revolution enabled it to regain control of its sovereignty, and its borders were closed once again. When its doors opened again, China did so on its own terms. The mystery of China remains because the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) keeps tight control of information. How did China become the powerhouse it is now? Why should the world pay more attention?

Joanna Chiu’s book, China Unbound: A New World Disorder, is an eye-opening exposé of the tactics China uses to increase its power and international influence. Chiu draws on over a decade of in-depth China-watching and reporting as a journalist to explain the reasons behind Beijing’s ambitions and to warn democracies around the world of the significant human rights, security, and economic implications if China reaches its goal of becoming the supreme global superpower.

China Unbound benefits from interviews with researchers at international economic, political and military think tanks, as well as academics in Asian studies, politicians, journalists, activists, and individuals who have been targeted by the Chinese state. Chiu spoke to people supportive and enthusiastic about China’s investment initiatives, as well as those who were more cautious and wary about the ultimate cost of those investments. She uses examples of events in Hong Kong, Canada, Australia, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Russia, and the United States to comment on China’s tactics.

She points to the role of Confucianism in the CPP regime: “Since assuming power of the CCP in 2012, Chinese President Xi Jinping has declared his admiration for the Chinese classics [like Confucianism] and is particularly fond of quoting ancient Legalist scholars to justify why it is in his citizens’ best interests to submit to a strong leader (p. 27).” Confucianism established a hierarchical social order of obedience in which “children must obey their parents, younger adults must heed their elders, and every citizen must be loyal to the emperor [now the State] (p. 26).” The tradition of Legalism postulated that since humans have a greater tendency to do wrong than right, strict rules, laws, and edicts were required to govern, which “empowered the emperor to rule effectively over a vast empire containing people of different ethnicities and cultures…. It was a kind of absolute power through bureaucracy (p. 27).” These traditional precepts seem equally true for the current Chinese regime.

She points to the role of Confucianism in the CPP regime: “Since assuming power of the CCP in 2012, Chinese President Xi Jinping has declared his admiration for the Chinese classics [like Confucianism] and is particularly fond of quoting ancient Legalist scholars to justify why it is in his citizens’ best interests to submit to a strong leader (p. 27).” Confucianism established a hierarchical social order of obedience in which “children must obey their parents, younger adults must heed their elders, and every citizen must be loyal to the emperor [now the State] (p. 26).” The tradition of Legalism postulated that since humans have a greater tendency to do wrong than right, strict rules, laws, and edicts were required to govern, which “empowered the emperor to rule effectively over a vast empire containing people of different ethnicities and cultures…. It was a kind of absolute power through bureaucracy (p. 27).” These traditional precepts seem equally true for the current Chinese regime.

Chiu explains how she approached her research on the book:

To understand Beijing’s quest for global power, I first had to understand the lengths to which the CCP tries to maintain control over its 1.4 billion citizens. The modern Chinese state was founded on revolution, so its leaders know all too well the power of the masses. In order to maintain control of such a huge population, instead of rule of law in China, there is rule by law, and it’s aided by high-tech surveillance. Laws and regulations govern virtually every aspect of a person’s life…. (p. 23).

This means that the State controls where you live, how many children (if any) you can have, where you are educated, what language you speak and cultural practices you keep, what your belief systems are, where you work, what information you have access to, and what you share on social media. Everywhere in China, and now in cyber-space, ubiquitous surveillance is made possible by the hacking of personal laptops and phones, and the tracking of IP addresses and on-line social network accounts.

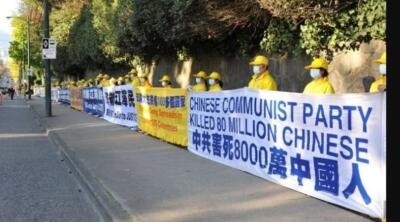

Since 2001, Vancouverites have seen Falun Gong practitioners outside the Chinese consulate, protesting against religious persecution in China. More recently, information about the mass detention of members of the Uyghur minority group – a mostly Muslim group who speak a Turkic language (p. 229) — have increased. Uyghurs live in Xinjiang, a resource-rich area in China’s farthest northwestern corner, next to Central Asia. Since the late 1800s, Han Chinese have been encouraged to relocate to Xinjiang, and more recently, the Chinese government has given them incentives to the detriment of the native Uyghur population. The overt discrimination has led to rising ethnic tensions, riots, and increasing talk of an independent Uyghur state, with the freedom for inhabitants to practice their Muslim faith. Exiles who have escaped, many to Turkey, have heard reports of whole villages being rounded up and disappeared into detention, or as Beijing calls them, “training” or “re-education” camps, purportedly to “…improve economic standards and aid in the fight against Islamist ‘extremism’” (p. 236). In some cases exiles’ families have also been taken into detention.

But even the exiles have not been free from harassment and intimidation. Ablet Jahanbag Yesi was able to get a visa to Turkey, but Chinese officials kept calling his new cell phone number to threaten him and his family. He can never return without fear of being detained and will probably never see his parents or siblings again. His message to the world through Chiu was: “Help save our children. Help them get a good education” (p. 254).

Chiu points out that not all Han Chinese officials toe the line on persecuting Uyghurs, “…and thousands were disciplined for allegedly dragging their feet, according to the Time’s leaked documents (p. 237).” In 2020, strong statements by the Canadian Subcommittee on International Human Rights condemned China’s actions against the Uyghurs as “genocide,” and legislation enacted by the United States that would punish Chinese officials responsible for human rights abuses in Xinjiang acted as mainly symbolic gestures. Without more concrete actions, Chiu warns, “Beijing’s ruthless treatment of minority groups should deeply worry leaders and citizens of democratic countries that support universal human rights. With China on the rise, what kind of global leader would it make if it became the world’s most powerful economy” (p. 237)?

Some of Chiu’s stories read like they came from spy novels, especially the tactics of the United Front Work Department, an agency that works closely with the Ministry of State Security, China’s secret police. Its goal is to encourage influential international individuals and organizations to promote Beijing’s policies, interests, and propaganda, and, Chiu notes, “it has also frequently been a means of facilitating espionage” (p. 75). United Front strategies include offering incentives including financial payments, free luxury tours to China, gifts, and appointments to a prestigious CCP advisory body, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. The famous Hong Kong actor, Jackie Chan is a member of this group.

The example of Australia’s then labour senator, Sam Dastyari is a case in point. He resigned in disgrace in 2017 after it was found that he had asked for and accepted payments to cover his government travel budget overruns from a Chinese organization linked to United Front; he had also accepted a free tour of China and made public statements contradicting the Australian government’s position by supporting China’s claim over disputed territory in the South China Sea. The scandal resulted in Australia passing new legislation to overhaul political donation laws and to protect against foreign investment, espionage, and counterintelligence.

If incentives don’t work, United Front conducts harassment and intimidation, such as tracking down Uyghur exiles. Closer to home, Chiu spoke with Port Coquitlam BC mayor Brad West, who has had a number of his constituents receive “…threatening phone calls and even in-person visits from Chinese government officials… to express anger over “little things, like a post on social media or an attendance at a certain event” (pp. 102-103). None of the individuals were well-known and all were first- or second-generation Chinese immigrants working in a variety of professions, and Chiu learned that many more people have experienced this kind of harassment and have been too afraid to report it. Yet Canada, unlike Australia, has yet to “pass legislation to make cross-border digital harassment illegal” (p. 104).

China considers all people of Chinese ancestry, no matter their nationality or citizenship, to be subjects of China. In 2019, Hong Kong citizens protested vehemently against a proposed extradition law that would allow anyone in Hong Kong deemed as criminals by China, from murderers to political dissidents, to be taken to mainland China for trial and imprisonment. The legislation passed in 2020 even after Hong Kong activists warned democratic governments around the world and Canada, the United States, and Germany “…issued statements of concern [and] later accepted refugees fleeing [Hong Kong]” (p. 89).

Hundreds of Hong Kong activists were taken to China for imprisonment as soon as the legislation was passed. But so were non-Chinese citizens. For example, John Clancey, an American lawyer practising in Hong Kong and who headed an organization associated with the pro-democracy movement, was the first U.S. citizen to be arrested. The example most familiar to Canadian readers is the kidnapping and incarceration in China of Canadians Michael Kovrig, a former diplomat, and Michael Spavor, who worked for a cultural organization, in retaliation against the arrest and house detention of Huawei’s executive Meng Wanzhou in 2018. Chiu continues that what is most concerning globally, is the fact that “Actions against China taken by individuals of any nationality outside the mainland may be considered violation of this law…. The global reach is clear, and many international legal experts quickly sounded the alarm to advise people of any nationality who ever said anything critical of Chinese or Hong Kong authorities to avoid travelling to greater China” (pp. 89-90), or on any transportation vehicle registered in Hong Kong or China.

History, again, gives us a clue to this aggressive quest for economic domination. China’s long turbulent history has included waves of foreign invasions. Perhaps most significant, in the current conflict with the West, is the “century of humiliation,” from 1839-1949, beginning when Britain and France defeated the Qing dynasty in the Opium Wars. As part of restitution payments, British troops emptied the Summer Palace of its priceless artifacts, and forced China to accept opium to be sold within its borders. Seeing how weak the country had become, other European countries, mainly Russia, Japan, and the United States, forced the empire to sign a series of treaties, referred to by the Chinese as the “Unequal Treaties.” These agreements — including the lease of Hong Kong to Britain and the creation of concession territories in ports such as Shanghai where foreigners were not subject to China’s laws — encroached on Chinese sovereignty. Perhaps China sees its current growth in power as a way of righting those historic wrongs.

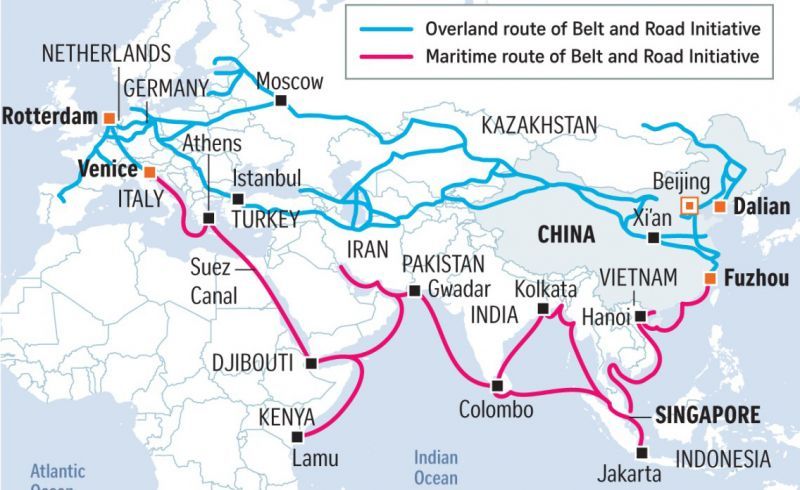

Revealing is Chiu’s expose of The Belt and Road Initiative, also called the New Silk Road, President Xi’s grand scheme to physically connect China to the rest of the world through the building, refurbishing, or buying of roads, railways, shipping ports, airports, pipelines and other infrastructure. “The project now spans more than 125 countries that have signed cooperation documents, according to Chinese state media, representing most of the world’s population and world economy” (p. 165).

In 2019, China’s spending on foreign direct investment was US$117 billion, making the country one of the world’s top bankrollers. Major recipients have included Hong Kong, the US, Singapore, and Australia, but the list also includes Canada, Britain (post Brexit), Italy, and Greece. China has even created an alternative to the World Bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (p. 164). Chiu quotes Bruno Maçáes, the author of Belt and Road: A Chinese World Order, that the project is a “change towards a more active foreign policy strategy, one aimed at shaping China’s external environment rather than merely adapting to it… The Belt and Road is the Chinese plan to build a new world order replacing the US-led international system” (p. 165).

But while investment deals offered to countries in financial straits might sound like manna from heaven, Chiu shows examples where the ultimate cost was higher than first anticipated. For example, when Greece’s economy was devastated by the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, the European Union imposed strict austerity measures in return for bailout packages to keep the Euro currency from collapsing. In 2009, COSCO, the Chinese state-owned shipping company, offered Greece €100 million a year for thirty-five years for the use of docking space and land around the strategic Port of Piraeus. Greece accepted willingly. Since then, Greece has sided with Beijing in United Nations votes on issues such as human rights and activities in the South China Sea, and has agreed to support the “One-China” policy with regard to Taiwan.

More recently, in 2016, COSCO bought a 51 percent stake in the entire port, with plans to make Piraeus the main Mediterranean gateway for the Belt and Road between Asia and Europe. Currently, most sea traffic between Asia and Europe goes through ports in Western Europe. While this project is seen as a Belt and Road success story, Greece has lost control of a historic commercial landmark, one of the region’s busiest container ports and Europe’s largest passenger port. Chiu quotes Nicolas Vernicos, a Greek shipping magnate who supports the Belt and Road project and is vice-chairman of the Silk Road Chamber of Commerce, with ties to United Front. “The Chinese found out that by financing the infrastructure of the countries you conquer them” (p. 208).

Sri Lanka is a good example of the so-called “Chinese debt trap diplomacy” tactic. The island nation, having incurred debts of US$1 billion to fund an overly ambitious port project, found itself unable to pay instalments. Wade Shepard, in Forbes Magazine in 2020, notes that the funds had been diverted to other uses. Instead of renegotiating the terms of the agreement, China took over the port, located in a strategic geographic location in relation to its most powerful Asian rival of India, for a ninety-nine-year lease. Shepard noted that China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank deals with countries with poor debt ratings, have a high incidence of corruption, and that the bank’s lack of oversight has resulted in many failed projects.

In Canada, while political leaders condemned human rights abuses and sent financial support to activist groups, trade missions — hoping Canadian businesses could penetrate its huge market — seldom raised the issue of human rights or rule of law. Since 2003, China has become Canada’s 3rd largest trading partner, and China did not hesitate to boycott canola, meat, and lumber products when Canada detained Meng Wanzhou on behalf of the United States. Despite this, although Canada is a member of the US-led “Five Eyes” intelligence network with United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, it has yet to join the group in rejecting Huawei’s 5G technology.

Australia is an interesting case study. Chiu notes that China is Australia’s largest trading partner, “to the point where some Australian industries [e.g. iron ore] have become entirely reliant on the Chinese market” (p. 144). In 2020, Australia signed a free trade deal with 14 other countries, including China, as part of the Asia-Pacific Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. When the deal was completed, China criticized Australia for calling for an independent inquiry into the origins of the Covid-19 virus, for rejecting Huawei, and for speaking out against human rights abuses in Hong Kong and Xinjiang. China then imposed tariffs on imports of Australian coal, beef, wine, and lobsters. The Australian government responded by applying the powers of its Foreign Investment Review Board to scrutinize all foreign investment proposals, including a number of Belt and Road projects. Chiu suggests that Australia could be a model for how to resist Beijing’s intimidation tactics but, she says, it is important for its allies, like those in the “Five Eyes” group, to provide concrete supports.

What of China’s relationship with Russia and the United States? In examining China’s relations with Russia, Chiu notes that Putin and Xi seem to enjoy a genuine personal connection and the two leaders have much in common, including the fact that they both vehemently oppose the United States. Historically, Russia has been an invader, but during the Chinese Communist Revolution, Russia acted as the big brother, and Russia is now more economically dependant on China, with Chinese extracting Russia’s natural resources. Time will tell whether Russia and China continue to present a united front as the United States rallies its international allies to counter Chinese and Russian interference and influence.

The United States has long been a Chinese adversary. “When President Trump and other American figureheads fail to uphold supposedly foundational American ideals like rule of law and democracy, this naturally invites outside accusations of hypocrisy,” Chiu notes. “China’s philosophy about global order is also opposed to allowing values like human rights to dominate international governance systems. Together, these factors, American and Chinese, weaken rules-based global institutions like the United Nations” (p. 316). The rhetoric and disinformation from both nations were ramped up during Donald Trump’s bid for re-election, accusations concerning the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic, and competing claims in the South China Sea that even threatened military confrontation. Chiu argues that what is required with the Biden administration — in partnership with other Western democracies — is a demonstration that “liberal values-based governance can indeed deliver greater public benefits than exists in authoritarian regimes.… Ultimately, America will be convincing as a global defender of democracy and human rights only if Washington practises what it preaches” (pp. 320-321).

But just relying on America and a change in leadership is not enough. There is a need in every country, says Chiu, to better understand China’s complex political realities: “Better policy rests on trying to understand issues deeply from all angles while considering the best way to hold Beijing accountable for human rights abuses and maintaining as much nuance and context as possible” (p. 326). More university Chinese studies and language programs would help bridge the gap in knowledge. Chiu urges policy-makers to realize that continued dialogue with Beijing is crucial, because there are still those within the CCP who do not necessarily agree with Xi on such issues as human rights violations. “But the window of opportunity may not last, as Xi consolidates his political power by purging his political opponents” (p. 316).

Finally, Chiu raises the issue of anti-Asian hate. Canada and the United States have seen periods of institutionalized racial discrimination, and the Covid-19 pandemic has once again brought xenophobia to the fore. China has used the issue of racism to deflect criticism from the CCP. But it is a mistake to think that people of Chinese descent, or even the Chinese people and the Chinese State, are one and the same, says Chiu.

Joanna Chiu is currently a senior correspondent for the Toronto Star. She has worked as a foreign correspondent based in Beijing and Hong Kong for Agence France-Presse, as China and Mongolia correspondent for Deutsche Presse-Agentur, and in Hong Kong she reported for the South China Morning Post, The Economist, and the Associated Press. She is also a member of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute and founder and chair of NüVoices editorial collective.

*

May Q Wong researches and chronicles the extraordinary in ordinary people. A graduate of McGill University, she holds a Masters in Public Administration from the University of Victoria and retired from the BC Public Service in 2004. Her first book, A Cowherd in Paradise: From China to Canada (Brindle & Glass, 2012), concerns a Chinese couple separated for half of their 50 year marriage, and the impact of Canada’s discriminatory laws on their family. City in Colour: Rediscovered Stories of Victoria’s Multicultural Past (TouchWood, 2018) (reviewed by Tom Koppel) concerns the diverse range of immigrants and their contributions to Victoria. In addition to reading, writing, and speaking to groups about her books, May creates useful and beautiful things with knitting and sewing needles – the latest being hand-beaded face masks. Editor’s note: May Wong has also reviewed books by Ben Maure, Bernard A.O. Binns & Ron Smith, Patrick Saint-Paul, Ian Greene & Peter McCormick, Beverley McLachlin, Graeme Taylor, Dukesang Wong, Henry Yu, Mei-Li Lee, Catherine Clement, and John Price & Ningping Yu.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1328 Money talks on the Belt and Road”