1311 The land of reading and writing

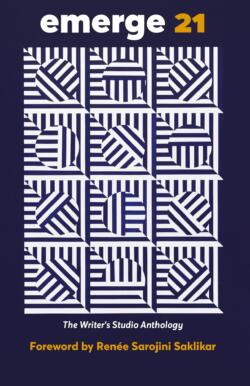

emerge 21: The Writer’s Studio Anthology

by Emma Cleary, Raoul Fernandes, Dayna Mahannah, Christina Myers, and KT Wagner (editors), with a foreword by Renée Sarojini Saklikar

Burnaby: Simon Fraser University, 2021

[price unknown] / 9781772870831

Reviewed by Michael Turner

*

For travellers who find reading and writing an essential service, I’m sure there is at least one anthology in your past whose gates you opened and explored its pages, finding yourself at home in some of its writings, losing yourself in others. Sometimes indifferent to voices that sounded like yours, other times attracted to those that did not. Sometimes, too, a neighbourhood of writings — if not the entire town — whose collective resonance rang greater than the sum of its parts. To the point where you might have wondered who it was that brought together and arranged these writings, and thus returned to its gates, to see who was responsible.

For travellers who find reading and writing an essential service, I’m sure there is at least one anthology in your past whose gates you opened and explored its pages, finding yourself at home in some of its writings, losing yourself in others. Sometimes indifferent to voices that sounded like yours, other times attracted to those that did not. Sometimes, too, a neighbourhood of writings — if not the entire town — whose collective resonance rang greater than the sum of its parts. To the point where you might have wondered who it was that brought together and arranged these writings, and thus returned to its gates, to see who was responsible.

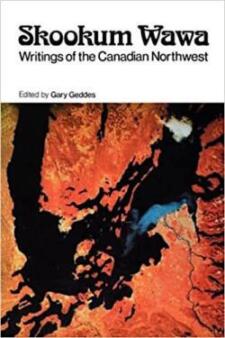

As a reader and a writer I have a list of anthologies I have stumbled upon, sought out, been gifted, assigned, contributed to, as well as edited that have had an impact on what I read more of and what I have written less on. As a high school student, it was poet-editor Gary Geddes’s Skookum Wawa: Writings of the Canadian Northwest (1975), a textbook focused not on nation, but on region (and the times being what they weren’t: not on Indigenous writers, but on that of settlers). Years later, at university, while many of us were assigned Norton’s door-stopping Anthology of English Literature, it was Alberto Manguel’s Other Fires: Short Fiction by Latin American Women (1986) that some of us read and discussed at bars and coffee houses, enthralled as much by its stories as some were critical of its editor’s arrangement of them, if not of the publisher’s decision to allow a man to edit a collection of women’s writing in the first place.

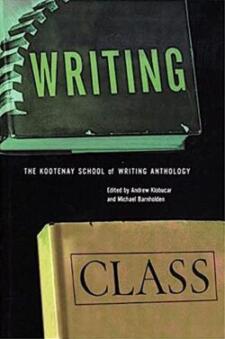

In the 1990s, “region” took a backseat to identity-based categories of gender (writing by women) class (“work writing”), race/racialization (diasporic, Indigenous) and sex (gay and lesbian), outpacing anthologies devoted to stylistic innovation (a postwar “tradition” inspired by Donald Allen’s New American Poetry, 1960) that included Canadian-based anthologies of concrete poetry (bpNichol’s The Cosmic Chef: an Evening of Concrete, 1970) and, somewhat belatedly, the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E-friendly poets included in Writing Class: the Kootenay School of Writing Anthology (1996), a publication so philosophically problematic that one of its classmates, Deanna Ferguson, refused inclusion based in part on another Marx’s (Groucho’s) refusal to belong to any club that would have her as a member.

Despite the historic difficulty retailers have in “moving” anthologies, they continue to be published, a reality that has as much to do with our 21st century shift toward relational inclusiveness as it does with the mandates of our culturally-progressive public granting agencies, the decolonization/emancipation of university curricula and the potential of social media to direct curious parties to order online that which is two clicks away. Leading the current crop of anthologies are those concerned with personal and planetary health. An ongoing yet under the radar category is the program-oriented anthology, like the one on the table beside me.

emerge 21: The Writer’s Studio Anthology (2021) is a production of Simon Fraser University’s Writer’s Studio, a year-long, certificate-granting program designed by Betsy Warland in 2001 and directed by her until 2012 (she remains on faculty to this day). Each year, TWS publishes an anthology of writing by program participants, and this year’s production might well be its largest. Totalling 451 pages, emerge 21 is divided into four sections — “Speculative and YA Fiction”, “Poetry”, “Fiction” and “Non-Fiction” — and includes the writings of 92 graduates, in addition to a Foreword by poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, a TWS graduate and now one of its instructors. Notable here is the “Speculative and YA Fiction” heading, a section comprised of subgenres that can be seen as a reflection of the mass market success of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games, Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves, not to mention the film-inspired revival of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

Of the 22 entries that make up the “Speculative and YA Fiction”, 18 are stated excerpts from longer works. The four that are not lead off the section and are indicative of what’s to come, but also of writers familiar with the subgenres in which they are working, from the dynastic clans of Juliet Goulet’s feudal gothic “Death Runs in the Family” and the equally melodramatic second-person death ritual consolations of Angie Antonopolous’s futuristic “Peace” to Amy Hogue’s present day recovery narrative “Falling Backwards” and the looping campfire story that is Noah Lefevre’s conceptual “The Clockmaker’s Curse”. Of the excerpted works, the first of which, M. W. Irving’s “The Bureau”, manages a linguistic and atmospheric restraint that allows its characters to develop not with dark room chemicals, but slowly, under sunlight. Roughly half the works in “Speculative and YA Fiction” favour this latter approach.

The “Poetry” section features the work of 16 writers, most of whom are represented by multiple entries. But let’s look at those who are not. The poems of Tricia Daum and Rachel Burns are landscapes, though each has chosen a different, if not contrasting, path. In Daum’s long-lined, four-page “Monica Meadows”, the landscape is both savoured and described. Indeed, the speaker identifies herself as “A witness/ of the Meadows, I write in my journal to share” (p. 114). And when not writing, she draws inspiration from “The mirrored lake/ [that] reflects, from across the valley, an ochre mountain group” and “spend[s] an hour watercolour painting/ the emerald gem bounded by a bedrock cliff” (p. 113). In Burns’s shorter, lyrically compact “a formula (for collecting clouds)” the landscape is a potentially haptic force, experienced less through sight than touch, its clouds there for the poet to “pluck” and “place,” ideally to where “the weight of the air could hold you” (pp. 136-137).

At 122 pages, the “Fiction” section is the longest. Unlike the “Speculative and YA Fiction” section, almost a third of the entries are stand-alone short stories. (What does this tell us about Speculative and YA Fiction? What does this tell us about the health of short fiction, despite the fact that there are fewer magazines and journals in which to publish it?). What’s more, whereas “Speculative and YA Fiction” opens with stand-alone works, “Fiction” opens with three longer excerpts, each of which (the first two in the third-person, the third beginning in the first-person) is concerned primarily with character. Thus primed, the occasion of the fourth entry, Kara van Donkersgoed’s very short stand-alone “A Body, Not Mine”, benefits as much from what it isn’t than for what it is: an interior work of lyric prose that would not appear out of place in the “Poetry” section. While the remainder of the section is largely focused on character and dialogue, what is most notable, apart from some very fine writing by some very well-read writers, is the range of voices and experiences that reflect the injuries and aspirations of our literature’s multicultural, intersectional moment. Yet nowhere is this more apparent than in emerge 21’s final section.

Of all the writing genres, none is mother to more sub-genres than the negatively titled genre we call Non-Fiction. Whether this is endemic to what this genre is not, or that the practitioners of its sub-genres are indifferent to classification, is something that is routinely discussed in Creative Writing Department curriculum meetings. Nevertheless, in terms of range of experience and stability of voice, emerge 21’s “Non-Fiction” section provides the information-seeking reader “real-life” (RL) reports on everything from a secular Turkish Jew’s pilgrimage to the annual Sufi celebration in Konya (Nuia Mana’s “Outspoken”) to a Saskatchewan grandchild’s multi-temporal, multi-spatial recollection of her grandmother’s landscape matching quilt (Fay Roth’s “56 Squares”).

Bookended by the “Non-Fiction” section’s opening and closing entries are many more works that could be classified under what has become, since the 1990s, the subgenre that threatens to consume all genres, and that is Memoir. Whether this trend is due to the confessional tendencies that characterize social media, a dissatisfaction with the artifice of Fiction or an impatience with Poetry’s ambiguities is, like the notion of genre itself, debatable. An indication of the totalizing ascendency of the memoir (known also as autoethnography and, coyly, autofiction) can be found in Julie Burtinshaw’s “Meet the Gang: The Stages of Grief”. Though Burtinshaw’s entry is reminiscent of the “self-help” subgenre, it is in fact an excerpt from her self-described memoir-in-progress (“It Takes a Long Time to Become Young Again”). The point here is that the pseudo-scientific “objectivity” that once guided self-help books is, like travel writing, cook books, how-to books, etc., now carried in the personal memoir.

I enjoyed reading the entries in emerge 21, from those very new to writing to those who have clearly been at it a while now. I delighted in the freshness of the new writers’ entries and I was often awed by the more experienced hands, some of whom are writing at a level on par with that which is celebrated today (you know who you are, right?). But as this is a book, and indeed an anthology, I admit to wishing that the book itself was more resonant, arranged less in accordance with genre than through, say, affective conditions, like those that inform our current moment. When I first received the book I noticed that nowhere on its cover was the name of its editor (or editors, as it turns out). Only on its “Production Credits” page, following the author bios, could I find “Section Editors” Emma Cleary (Fiction), Raoul Fernandes (Poetry), Dayna Mahannah (Fiction and Non-Fiction), Christina Myers (Non-Fiction) and KT Wagner (Speculative and Young Adult Fiction), each of whom presumably selected and sequenced the entries in accordance with the book’s section headings.

I realize it is a lot to ask of our hyper-accelerating, surface-signifying, atomizing time that we make qualitatively more of that than we are contracted to fulfill. But emerge 21 is no longer the program its writers signed up for; it is the book that sprouted from it. And as a book, should it not resemble less the strictures of the program that graduated its writers than the book its writers, with the pollination of its editors, produced? A favourite moment in my reading experience came after Kara van Donkersgoed’s poetic “A Body, Not Mine”, an entry that, as I mentioned earlier, followed the three fiction excerpts that opened its section. This kind of generic intermingling was something Geddes did so well in Skookum Wawa and, despite that anthology’s shortcomings, set this high schooler, this traveller, on a path of no return, to the land of reading and writing.

*

Michael Turner is a writer of variegated ancestry (Scottish/ German/ Irish, mat.; English/ Japanese/ Russian, pat.) born, raised and living on unceded Coast Salish territory. He works in narrative and lyric forms, both singularly, as a writer of fiction (American Whiskey Bar, The Pornographer’s Poem, 8×10), poetry (Hard Core Logo, Kingsway, 9×11), criticism and music, and collaboratively, with artists such as Stan Douglas (screenplays), Geoffrey Farmer (public art installations) and Fishbone, Dream Warriors, Kinnie Starr and Andrea Young (songs). His work has been described as intertextual, with an emphasis on “a detailed and purposeful examination of ordinary things” (Wikipedia). He holds a BA (Anthropology) from UVic and an MFA (Interdisciplinary Studies) from UBC Okanagan. Currently he is an Adjunct Professor in the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences and School of Interdisciplinary Studies and Graduate Studies, Ontario College of Art & Design University and a workshop leader at Mobil Art School, Vancouver. Editor’s note: Michael Turner has also reviewed books by Tara Borin, Taryn Hubbard, Jen Sookfong Lee, Isabella Wang, and Sachiko Murakami for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1311 The land of reading and writing”