1157 Poetry for the wider world

I will be more myself in the next world

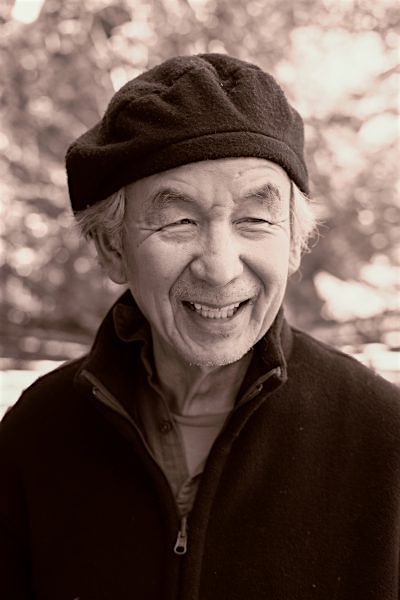

by Matsuki Masutani

Salt Spring Island: Mother Tongue Publishing, 2021

$19.95 / 9781896949871

Reviewed by Ken Madsen

*

Full disclosure: I know Matsuki Matsutani. I met him almost a decade ago, after my wife Wendy and I moved south from the Yukon to the same small gulf island where Matsuki lives. On an island like Denman, people’s orbits intersect at unpredictable times and places. I first met him on the other side of a table tennis net, then at a local lake, then periodically in downtown Denman Island. Eventually he invited me to play a game of “Go.” He politely clobbered me game after game and when I showed no sign of grasping even the basic strategies of the game we switched to chess.

Full disclosure: I know Matsuki Matsutani. I met him almost a decade ago, after my wife Wendy and I moved south from the Yukon to the same small gulf island where Matsuki lives. On an island like Denman, people’s orbits intersect at unpredictable times and places. I first met him on the other side of a table tennis net, then at a local lake, then periodically in downtown Denman Island. Eventually he invited me to play a game of “Go.” He politely clobbered me game after game and when I showed no sign of grasping even the basic strategies of the game we switched to chess.

My next disclosure is that although I’m an avid reader of non-fiction and many genres of fiction, I practice social distancing when it comes to poetry. I blame it on stupefying English classes in high school. I still shudder when I remember tedious, hour-long classes listening to barely literate classmates reading verse out loud while the rest of us stared out the windows in despair.

A couple of years ago Wendy bought a slim volume entitled Love of the Salish Sea Islands, a collection of essays, memoirs and poems by island writers [reviewed here by Theresa Kishkan — ed.]. I leafed through the book until I came to a poem by Matsuki:

Long ago in a classroom

I heard about

a utopia called

“The Village of the Peach Blossoms.”

Many of my friends

Even the girls,

soon dismissed this as fantasy.

But I never forgot

the image.

Now

I realize

I am in it.

I am inside that image,

standing in a garden of apple blossoms.

To get here

I left my country,

my city life,

even my career.

I must be nuts.

I have stood in Matsuki’s garden of apple blossoms and eaten apples that have magically sprung from those blossoms. Maybe that explains why I was instantly hooked by his poetry.

You’ll have to forgive this analogy, but I am the author of Paddling in the Yukon – a Guide to the Rivers, and I spent many northern summers “scouting” rapids, trying to find a way to safely paddle my kayak or canoe through the whitewater. The surface of a river reveals only part of its story. Hidden obstructions below the surface create confusing currents, waves and eddies. When you scout a rapid it is called “reading” the river, and absorbing Matsuki’s poems is like that. What flows on the surface hints at hidden depths.

I will be more myself in the next world is a remarkable volume of poetry. The writing is honest and engaging. It is also deceptively simple. I found that I was reading the poems at one level, but understanding them at another. The celebrated poet and novelist Joy Kogawa says, “The poet Greg Cogswell spoke of ‘star people.’ You chance upon them. They emanate a certain deep inner glow. Matsuki Masutani has that bright starlight. You will know it when you meet/read him.”

Matsuki’s poems range widely in their subject matter from everyday living situations to serious health concerns to the tragic death of a young friend. One of the charming qualities of many of Matsuki’s poems is that they are funny. I don’t often snort with laughter, but it happened time after time as I read. He has a calm style of writing, but every so often he throws in a zinger that smacks me right on my funny bone.

I woke up

from a nap

remembering the sensation

of driving fast

around a sharp

curve

but I could not

remember where

I was going.

It was as if

the road had vanished

right in front

of my speeding car.

it bothered me

and I recalled

my wife saying

that people who take

naps tend to lose

their minds.

Matsuki was born in Japan on January 1st, 1946, just 5 months after atomic bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but his family never talked about the war and its impact on Japan. His father was an academic who taught philosophy and religious studies. Unlike many parents who hope their kids become doctors or lawyers, Matsuki was encouraged to write and his father prized poetry as an important art form.

Matsuki wrote poetry in Japanese when he was in his early 20s and hoped that it would be a gentle way of changing the world. He was influenced by the cultural revolution and, like many academics in China, decided to see if manual labour would lead to the truth. He worked on a farm, but by the late sixties he decided that radical political protest would be more effective in bringing about societal change than by working with calloused hands or writing poetry. He and his activist friends joined the anti-Vietnam War protests and at one point he was jailed for 20 days for his actions.

In his poem “1970 Kawasaki, Japan,” Matsuki details the tragic death of a friend. This young man cared so deeply for the cause that he emulated Vietnamese Monks who had burned themselves to death in protest.

1970 Kawasaki, Japan

you passed away

at sunrise

with an apology to your parents,

echoing Vietnamese monks,

you prayed, meditated

and set yourself on fire to protest the raging

imperial war.

You were twenty-one.

Your father was a steel co.

executive, probably profiting

from the war.

In his grief he invited us,

your friends,

all student radicals,

to a fine Japanese restaurant

to commemorate you,

his only son.

He said, “Please

drink and talk

as if my son were

with us.”

After the feast

we made a circle for the last time.

The radical movement

was in chaotic decline.

I remember

one of us broke

the silence,

“Let’s not forget

he is part of us.”

Unexpectedly

we had to carve out

new lives for ourselves

for better or worse.

Most of us quit

university.

Some even

left the country.

Matsuki was one of those who left Japan. He got a job in Saigon, “met a girl with a nose ring and moved to Canada.” After living in Vancouver for many years he and his wife Jane moved to Denman Island. He stopped writing poetry and worked at odd jobs. He was a carpenter’s assistant, a gardener, a worker on an oyster lease, a translator. In 1999 he suddenly started writing poetry again, this time in English. The whole time he thought about his parents and wondered whether they could ever approve of his life choices.

I ran away

from my father

to find out

who I was

now, forty

years later

I look back

at my father

and wonder

who he was.

Matsuki had no intention of publishing his poetry, he simply felt the need to write. He wrote a series of poems after he was diagnosed with cancer in 2018. The poems were forwarded to a friend who also undergoing cancer treatments. She treasured the poems that helped her through a difficult time. When he heard about that, he decided that it was time for his poems to get out to the wider world. His daughter Hanako sent them out and his poetry was published in Geist, the Capilano Review, and in Love of the Salish Sea Islands. And now this volume, I will be more myself in the next world.

Publishing poetry is an act of courage. In a few spare words, there is nowhere to hide your thoughts and feelings. Despite knowing Matsuki Masutani, I learned new and deeply personal things through reading his poems. We are lucky that his poetry is now out in the wider world for all of us.

*

Ken Madsen is a former writer, photographer, and conservation activist. He lived in the Yukon Territory for more than three decades. He was instrumental in the successful campaign to protect the Tatshenshini-Alsek watershed, now part of a provincial park and a World Heritage Site. He worked for years on the ongoing battle to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and many other conservation issues in the north. He has written four books including Paddling in the Yukon, Wild Rivers-Wild Lands, and Under the Arctic Sun. He has also written numerous articles for magazines such as Canadian Geographic and BC Magazine. He currently lives happily on Denman Island with his partner Wendy Boothroyd. Editor’s note: Ken Madsen has previously reviewed Kings of the Yukon: A River Journey in Search of the Chinook, by Adam Weymouth, for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1157 Poetry for the wider world”