1114 Steveston, Powell Street, Minto

Chiru Sakura — Falling Cherry Blossoms: A Mother & Daughter’s Journey through Racism, Internment and Oppression

by Grace Eiko Thomson

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2021

$24.95 / 9781773860411Reviewed by Patricia E. Roy

*

In 1997, for the benefit of her children and grandchildren, 84-year-old Sawae Nishikihama began writing memoirs of her experience as a Japanese Canadian. After her death in 2002, her daughter Grace Eiko Thomson translated them from Japanese and wove extracts into her own memoir. The subtitle, “A Mother & Daughter’s Journey through Racism, Internment and Oppression” describes the theme. While a contribution to Japanese-Canadian history, the book is also a study of the “complicated relationship” of a “strong mother and a stubborn, though always obedient, daughter” (p. 10) and especially, of Grace’s search for her identity.

In 1997, for the benefit of her children and grandchildren, 84-year-old Sawae Nishikihama began writing memoirs of her experience as a Japanese Canadian. After her death in 2002, her daughter Grace Eiko Thomson translated them from Japanese and wove extracts into her own memoir. The subtitle, “A Mother & Daughter’s Journey through Racism, Internment and Oppression” describes the theme. While a contribution to Japanese-Canadian history, the book is also a study of the “complicated relationship” of a “strong mother and a stubborn, though always obedient, daughter” (p. 10) and especially, of Grace’s search for her identity.

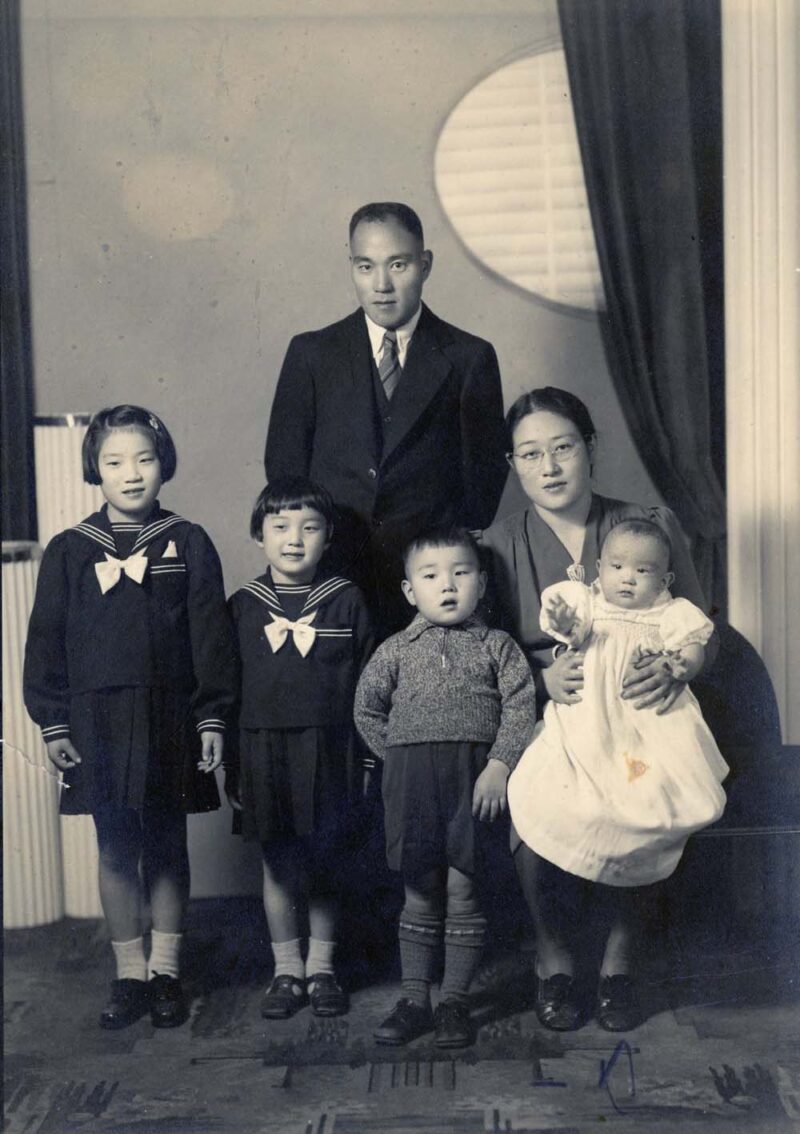

Sawae Nishikihama (nee Yamamoto) was born in 1913 in Mio Village in Wakayama, a village known for the high proportion of its residents who came to North America. Her father had fished at Steveston and two older half-brothers settled there. Two sons of another Mio family, the Nishikihamas also fished from Steveston. In 1921 Torasaburo, the youngest, joined them. In 1929, his family called him back to Japan to marry Sawae. The newlyweds travelled together to Steveston where they lived with one of Torasburo’s older brothers, his wife and five children. Some months later, the other brother, his wife, and infant joined them.

In November 1931, Sawae gave birth to a daughter and, two years later, to Eiko, the author of this book. When the Depression made earning a living difficult, the older Nishikihama brothers sent their wives and children to Japan. Torasaburo secured a position as a fish buyer and moved his family to Paueru Gai, the centre of Japanese settlement in Vancouver’s Powell Street area.

Sawae fondly remembered Paueru where the availability of Japanese goods and services meant her limited knowledge of English was not a handicap. The support system there, Thomson suggests, explains why the Issei (the immigrant generation) retained nostalgia for it. In 1939 the family sent their eldest child, Kikuko to visit her grandmother in Japan. The Sino-Japanese war thwarted their plans to visit Japan the next year and bring her home. Then, Canada declared war on Japan and, in February 1942, ordered all people of Japanese ancestry to leave the coast.

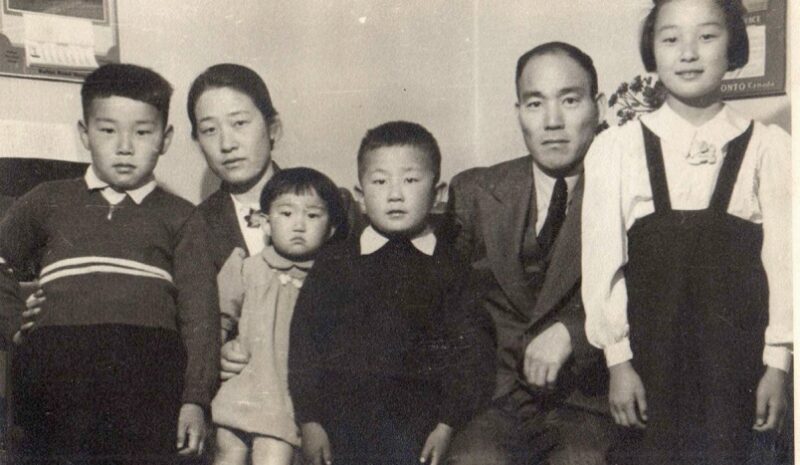

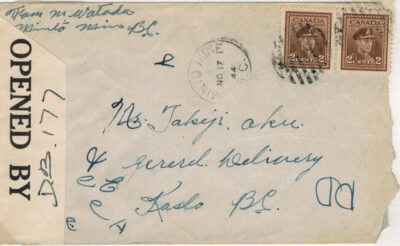

The Nishikihamas heard of movement to the prairies and to the interior internment centres, but following the advice of Sawae’s brother-in-law, the family, now including four children, among them a newborn, chose to go to a self-supporting settlement at Minto, an old mining town in the Bridge River Valley. After the government ordered Japanese Canadians to move east of the Rockies or to Japan, the Nishikihamas signed to go to Japan where they had relatives including their oldest daughter. After learning of the poor conditions there, they changed their minds and went to Manitoba where they eked out a living on a farm which provided substandard housing. They soon regretted their decision, but Sawae mused, “there is no remedy for a wrong decision once the decision is carried out” (p. 71). In time, her husband found better-paying jobs. The family moved to another rural community and, after the war, to Winnipeg where they saw their children educated, bought a house, and brought their daughter back from Japan. Sawae, who had supplemented the family income by dressmaking, worked full time in a garment factory. After retirement, Vancouver’s milder weather drew them back to the coast.

Because the publisher used a very slight indentation, not a different typeface, to set off Sawae’s writings, it is sometimes necessary to read a few lines to identify the narrator. The difference becomes clear. Despite exploitation by in-laws and disagreements with them over money and childcare, Sawae’s memoirs of her day-to-day life express resignation, reflecting the Japanese adage, shikata ga nai: (it can’t be helped).

Grace, however, remembers her mother as being frustrated and bitter. For Grace, writing her memoirs was “a therapeutic act, moving toward resolution of a past that I had always held in abeyance as insoluble” (p. 125), namely “the psychological scars and memories of injustice [which] remain with many” Japanese Canadians (p. 130). Those problems were complicated by experiences of misogyny in the workplace, possibly exacerbated by childhood incidents when men — a young Japanese at Minto and a town clerk in Manitoba — forcefully kissed her. In neither case did she report the incident to her mother or anyone else.

From an early age, Grace felt insecure, of not being sure of who she was, although she accepted “racialized life as the norm” (p. 108). Among her scattered memories of childhood in British Columbia is that of being a “misfit” at Minto because her Japanese Canadian classmates who came from better off families learned the latest “Hit Parade” songs from their families’ radios and phonographs, whereas she only knew Japanese songs taught by her mother. At least at Minto she was not distinguished by race as she was when, as an eleven-year-old at a country school in Manitoba, she and her younger brothers were treated as “different” and “made to feel inadequate” p. (76) especially by a teacher who could not pronounce “Eiko” correctly. The next school year, she registered as “Grace.”

As a newcomer to Winnipeg, she was not comfortable among other young Japanese Canadians who had assimilated into both their own and the larger community. When a high school English teacher read her composition on daily life to the class, she wondered was it because it was good, or because it was exotic? Feeling that discrimination made her a “misfit,” Grace was so anxious to please others that her mother feared friendliness could get her into trouble.

Some people were kind. Striking examples were the man who employed her as a secretary and his wife who took her to football games and symphony concerts. This “contributed greatly” to her becoming “a woman confident enough to begin pursuing her own direction into the future” (p. 123). And she appreciated the warm welcome given by the Scottish-Canadian Thomson family when she married their son.

As a young woman she had had a “revelation” about her Japanese Canadian identity. In the public library she accidentally found Forrest LaViolette’s sociological study, The Canadian Japanese and World War II (University of Toronto Press, 1948). It “connected the dots” and made her aware of the history she had lived through (p. 110). Well into adulthood she realized that it was the racists who lacked self-esteem. Seeking to analyse this, Grace took university courses that led to a B.F.A. from the University of Manitoba. Still searching for her own identity, she left her husband and two teen-aged sons in Winnipeg and went to the University of British Columbia to study Asian Art. These studies made her proud of her Asian heritage, but led her to leave her marriage and family in order to continue her journey “toward self-realization” (p. 141).

As a young woman she had had a “revelation” about her Japanese Canadian identity. In the public library she accidentally found Forrest LaViolette’s sociological study, The Canadian Japanese and World War II (University of Toronto Press, 1948). It “connected the dots” and made her aware of the history she had lived through (p. 110). Well into adulthood she realized that it was the racists who lacked self-esteem. Seeking to analyse this, Grace took university courses that led to a B.F.A. from the University of Manitoba. Still searching for her own identity, she left her husband and two teen-aged sons in Winnipeg and went to the University of British Columbia to study Asian Art. These studies made her proud of her Asian heritage, but led her to leave her marriage and family in order to continue her journey “toward self-realization” (p. 141).

After finishing her studies at UBC, for seven years she worked as an assistant director/curator at a University of Manitoba Art Gallery. Using funds from the Japanese Canadian Redress Agreement, she took leave and went to the University of Leeds for graduate studies. Under the direction of a feminist scholar, she hoped to continue discovering herself as a person of Asian descent and as one who faced misogyny in the workplace. The latter was confirmed when, in her absence, her position in Winnipeg was abolished for “economic reasons;” she blamed misogyny (p. 149). Concluding that “no way a woman like me could win” (p. 150), she abandoned an appeal and accepted a position at the Little Gallery in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, where she spent three happy years.

To care for her aging mother, however, she returned to Vancouver. An interview with the Vancouver Art Gallery was uncomfortable but the Burnaby Art Gallery hired her as a curator. She also became involved in the local Japanese Canadian community and through its 1992 Homecoming Conference met Japanese Canadian artists. She also curated several cross-cultural exhibits. Through this work she developed the confidence to share her experiences with others. After the city took over the Burnaby Art Gallery, she found working with “male bureaucratic control” difficult,” and so resigned.

About this time, planning for the Japanese Canadian National Museum in Burnaby was underway and she was invited to serve as a consultant. Her voluntary work led to a paid position as executive director/ curator. With the help of part-time staff and volunteers, she secured grants and planned exhibits telling the story of the internment and the fight for justice. Such stories, she asserts, “call into question our assumption that we are a country with an impeccable human rights record” (p. 161).

Because she felt that the president of the board of directors did not respect the knowledge or experience of the professional staff and volunteers, once the museum was open, she resigned. She reflects, “women who speak out on issues” are often called troublemakers while men who speak out are “recognized as community leaders” (165). Although she does not like the term “Nikkei,” which applies to any Japanese living overseas and not specifically to Japanese Canadians, after the Museum became part of the Nikkei Heritage Centre, she accepted a contract to complete two exhibitions that she had initiated.

Her association with the Japanese Canadian community continued and she was elected to the executive of the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC). Through it she participated in successful protests of the Canadian War Museum’s portrayal of the Japanese internment and of the proposed naming of a new federal government building in Vancouver after Howard Green who, as a Member of Parliament, had urged the internment and deportation of Japanese Canadians.

Grace Eiko Thomson continues to participate in cross-cultural activities including those with Indigenous peoples whose artistic endeavours she first appreciated when, through the University of Manitoba, she assisted in selecting Inuit prints to be sold in the south. Her friendship with Indigenous people continued. From Chief Robert Joseph, who spoke at a NAJC banquet, she learned that “reconciliation, a goal I had earlier doubted was possible, must begin firstly within oneself.” “We are indeed all one,” she concludes, “it is up to us, each one of us, to insure justice for all” (p. 191). At last, Grace Eiko Thomson had found her identity; this book is the result of that search.

*

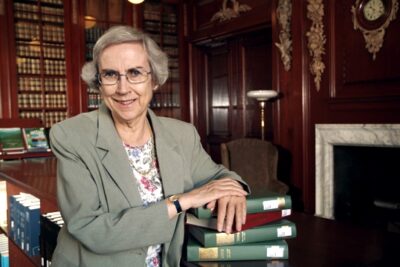

Patricia E. Roy, a native of British Columbia, is professor emeritus of History at the University of Victoria where she taught Canadian history for many years. Her own research has been mainly in the field of British Columbia history and she is best known for her trilogy of books on the responses to Chinese and Japanese immigrants: A White Man’s Province (1989), The Oriental Question (2003), and The Triumph of Citizenship (2007). All were published by UBC Press. Her longstanding interest in B.C.’s political history resulted in Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (UBC Press, 2012). Her latest book is The Collectors: A History of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives (Royal British Columbia Museum, 2018). Editor’s note: Patricia Roy has most recently reviewed books by George M. Abbott, Jesse Donaldson, Linda Kawamoto Reid, John Endo Greenaway, & Fumiko Greenaway, Kotaro Hayashi, Fumio “Frank” Kanno, Henry Tanaka, and Jim Tanaka, and Ian Ferguson for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1114 Steveston, Powell Street, Minto”