1097 HRH: A nodding acquaintance

MEMOIR: HRH: A nodding acquaintance

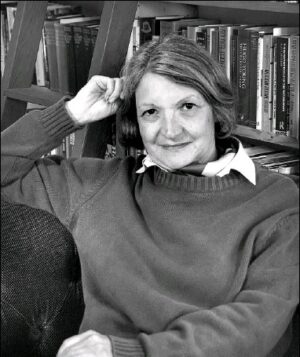

by Maria Tippett

*

On the occasion of the death of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (1921-2021), we present an extract from the diary of art historian Maria Tippett of Pender Island of the visit to Trinity Hall, Cambridge, by Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh in November 2000.

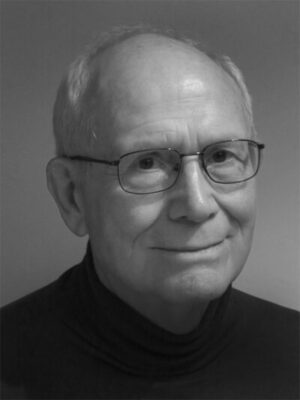

Victoria native Tippett was then a fellow of Churchill College, and her husband, Professor Peter Clarke, was master of Trinity Hall — Ed.

*

24 November 2000. Journal, Cambridge.

We were awakened yesterday morning around 6 AM by yelping dogs — sniffing for bombs — and the soft voices of police officers checking out the Lodge. Prior to the Queen’s arrival, it had begun to pour – and I mean a real Vancouver-style downpour. It was still raining as Peter and I duly waited at the college gate, for the arrival of Her Maj, as we’ve been calling Queen Elizabeth. Then, suddenly, the Queen, dressed all in red, appeared with the Duke walking four paces behind her. The Royal Standard — which Buckingham Palace had sent us last week — was unfurled on the college’s flagpole and introductions took place.

Peter had made it clear to everyone in the college that neither bowing nor curtseying were mandatory, “A simple nod of the head will do if one feels so inclined.” I did not nod, but Danielle Lyons made up for my indiscretion by curtseying so deeply that she could barely rise to her feet. The Queen had a firm but not a bone-crunching handshake.

After these introductions, everything — with the exception of the rain — proceeded according to schedule. During our procession from one building to another I shared the Duke’s umbrella exclaiming that it was not every day that I had a Duke hold an umbrella for me. Peter remained with the Queen and duly reached the Lodge. Then, as planned, she withdrew with her three ladies-in-waiting to one of our guest rooms to rest before lunch and to fortify herself with a stiff drink of gin and DuBonnet — ugh! Meanwhile, the Duke also retreated to another of our guest rooms and downed a bottle of beer.

Half an hour later, we all gathered in the Lodge then processed into the hall for a much-needed lunch. Peter gave a welcoming toast to the Queen, which seemed to break the ice because the noise level in the Hall rose substantially. The Duke, seated on my right, was more convivial than I had anticipated. I told him how I had been among the grade-school pupils at Doncaster Elementary School in Victoria, British Columbia, who had waved their flags as he and the Princess drove by us in their open-top convertible. “Ah yes, that was during our tour of Canada in 1951,” the Duke replied, “and after visiting Victoria, we drove up Vancouver Island to a place called Qualicum.” I did not correct his mispronunciation of Qualicum, simply congratulated him on his sharp memory of events half a century ago. He then asked me if Trinity Hall had any ghosts. I told him that there was indeed one in the Master’s Lodge, which he clearly found amusing.

When we had finished eating, Peter rose and gave a hilarious A-plus speech – peppered with many a “Ma’am,” which he remembered not to confuse with ham or jam.

By this time, it was after 2:30, and we proceeded through the rain to the renovated room under the Old Library, which the Queen was formally opening, in honour of the renowned Dickens scholar, Graham Storey, a Fellow of Trinity Hall, who was happily present. We also spent half an hour or so viewing the college’s collection of silver — one of best in England — and the blindfold that Terry Waite had worn during his five-year incarceration in the Middle East. Then, following another short speech from Peter — it was so brief it did not warrant a grade — the Queen pulled back the blue velvet curtain covering the commemorative plaque. We all clapped and Graham Storey blushed as he bowed his head.

With this short ceremony over, it was now time for the Duke and Queen to leave and for everyone to get back to work. Everyone, that is, with the exception of the Royal couple who, the Duke informed me at lunch, began their weekend on a Thursday — perhaps with their work now done. Though I had not been looking forward to the Royal Visit, I thought it was terrific. The Queen was not only professional as one would expect; she was a real trouper. She could have darted from one building to another to avoid the rain. But she insisted on spending time with the rain-drenched students who had been assembled outside since early morning. Because of this, she had to change her high-heeled shoes at least twice. Nor did the Queen flinch when Peter broke with protocol, as I noticed, by placing his arm around her shoulder as he guided her from one reception to another. In fact, she seemed to like it!

We accompanied the Queen and the Duke back to the Lodge so that they could retrieve their coats and have a pee before their two-hour journey to Sandringham. Then, as the Queen returned to the entrance hall of the Lodge, I saw her take something from her handbag. A closer look revealed that she was holding a massive brooch studded with diamonds and pearls. She seemed to be having some trouble pinning it on to her lapel so I asked if I could help. She nodded, then placed the magnificent piece of jewellery in my hand. The clasp, of the stick-pin variety, had a very long shaft. This made me wonder what would happen if the pin slipped from my chubby fingers and stabbed the Queen in the chest. But it did not. Even so, perhaps fearing that I had not been as efficient as her three ladies-in-waiting (who had now left for London after lunch) the Queen asked me to reassure her that I had indeed secured the brooch to her lapel. I checked the clasp twice, saying “Yes Ma’am” as I did so.

After doing this, the Head Porter appeared with a see-through wrap-around umbrella and led the Queen to a Land Rover, parked in the college court a short distance from the front door of the Lodge. I was left standing outside our entrance hall in the rain with the Duke who was trying desperately to unfasten the strap around his brolly. Unaccustomed to performing this simple task for himself, he failed. Unwilling to perform two menial tasks within a few minutes, I offered him no assistance.

Head and coat unprotected, the Duke nonetheless ventured into the rain, opened the door on the Queen’s side of the car and placed a rug across her lap. Then he paused for a moment, gave Peter and me an appreciative nod, ran around to the other side of the car and — after a large security man had folded himself into the back seat of the Range Rover — the Duke himself took the wheel. As he revved up the powerful motor then sped out of the college, the flower beds, so carefully tended by the gardeners, were sprayed with tiny pieces of gravel.

After the Duke and Queen departed, Peter went off to talk to a potential donor who had come from the United States to Cambridge for the royal visit. Meanwhile, I occupied myself by answering e-mails and shuffling a few papers in my study. When Peter returned from his meeting we cycled to Clare Hall for a swim. The exercise set us up for an evening’s dining in hall with the graduate students. Needless to say, we skipped the port and snuff after dinner and were both in bed by 9:15 p.m.

Well, we woke up at 2 a.m., buzzed. Unable to sleep, we had a post-mortem on the day’s events. We noted how everyone in the college had worked so very hard to help make the visit a success. Some of them were rewarded by seeing themselves on the BBC’s 6 o’clock news that evening. We also commented on how there had been almost no contact between the Duke and the Queen during the entire visit. Over lunch the Duke repeatedly referred to his wife as “the Queen” as though she was an untouchable object. I told Peter I was also surprised to observe that the Queen looked and acted much older than the Duke. Peter told me that she had lovely legs for a woman in her early seventies. But, really, they were just two elderly people getting on with their jobs. We agreed that we would not like to host this sort of event too often.

*

Maria Tippett spent the formative years of her academic career as sessional lecturer at Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia, and the Emily Carr College of Art and Design. Following her year as Robarts professor of Canadian studies at York University (1986–7), she lectured in South America, Europe, and Asia and curated exhibitions. In 1991, she returned to academe, becoming a member of the Faculty of History at Cambridge University and a senior research fellow and tutor at Churchill College, also at Cambridge. Since her formal retirement in 2004, she has written four books, including Sculpture in Canada: A History (Douglas & McIntyre, 2017), reviewed here by Catherine Nutting. Among many awards, in 1980 she won the Sir John A. Macdonald Prize for her path-breaking Emily Carr: A Biography (Oxford University Press, 1979), which also won the Governor General’s Award for non-fiction. Editor’s note: Maria Tippett has also reviewed books by Kaija Pepper, Mary Fox, Ruth Abernethy, and Roger Boulet for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1097 HRH: A nodding acquaintance”