#985 Open scenery, hidden history

Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

by Eve Lazarus

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2020

$32.95 / 9781551528298

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

*

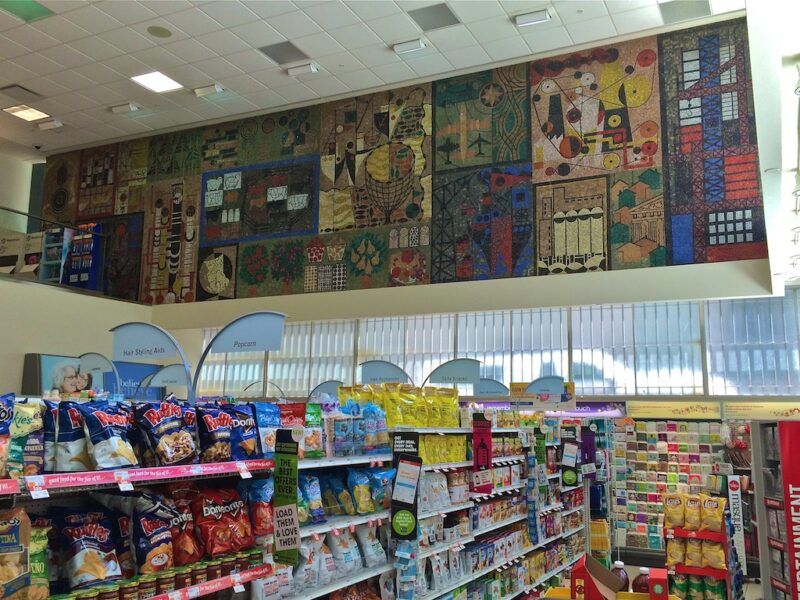

As a lifelong Vancouverite, arguably the Canadian equivalent of a native New Yorker, I’m habituated to the abundant charms of Vancouver, which doubtless prevents me from noticing a veritable panoply of observable phenomena in, and about, my hometown. Apart from bookshop and food recommendations, I’m an unforgivably abysmal authority on my city. Thank God for Eve Lazarus, an Australian expatriate who has lived in the North Shore for over two decades, and her generous outpouring of historical knowledge and fun facts, which are admirably bountiful in Vancouver Exposed. Believe me when I say Vancouver Exposed is wide-ranging. Belly flops, polar bear swims, nudists, spite houses, the skinniest building in the world, the unceremonious destruction of beautiful buildings, an unexpected ceramic mosaic by a Shoppers Drug Mart, and unsavoury history Vancouver might rather have us forget — it’s all here.

As a lifelong Vancouverite, arguably the Canadian equivalent of a native New Yorker, I’m habituated to the abundant charms of Vancouver, which doubtless prevents me from noticing a veritable panoply of observable phenomena in, and about, my hometown. Apart from bookshop and food recommendations, I’m an unforgivably abysmal authority on my city. Thank God for Eve Lazarus, an Australian expatriate who has lived in the North Shore for over two decades, and her generous outpouring of historical knowledge and fun facts, which are admirably bountiful in Vancouver Exposed. Believe me when I say Vancouver Exposed is wide-ranging. Belly flops, polar bear swims, nudists, spite houses, the skinniest building in the world, the unceremonious destruction of beautiful buildings, an unexpected ceramic mosaic by a Shoppers Drug Mart, and unsavoury history Vancouver might rather have us forget — it’s all here.

Vancouver is a young city, an observation not lost on Douglas Coupland in City of Glass, a highly complementary co-read written in cavalier, authoritatively opinionated prose often bordering on prescient. He writes that:

First Nations history in Vancouver goes back four or five thousand years, maybe longer. European settlement only goes back a bit more than a century, and some people don’t like this lack of recent European history. Most often it’s eastern Canadians (but not Americans, for some reason) who arrive in town only to undergo a psychic disaster akin to a deep-sea creature being raised to the surface . . . This place is too new!

If you’re a Vancouverite, you find the city’s lack of historical luggage liberating — it dazzles with a sense of limitless possibility (p. 58).

If we pay attention to the subtitle of Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History, it seems clear that Lazarus is well-aware of this widespread notion espoused by Coupland that Vancouver, comparatively speaking, lacks history; however, comparatively lacking (European) history is hardly the same thing as actually lacking history, an important distinction. Rather, Vancouver’s history has not, perhaps, been fully excavated.

Certainly, the “hidden” history indicates that Lazarus is inviting us to discover the little known, the quirky, and the legitimately ugly, and she does so with zeal. I found myself delighted and also occasionally appalled at my own apparent lack of knowledge for Vancouver history. Joe Fortes isn’t just a seafood restaurant, but was a real person from Trinidad, and also Vancouver’s first lifeguard? I was floored, then embarrassed. It was a bit like the chastening realization that avocados don’t originate from the grocery store in the same way that Athena sprouted from Zeus’s head.

I can only assume fellow Vancouverites are probably less asininely ignorant than I am, but regardless of your level of esoteric Vancouver knowledge, there is mind-bogglingly plenty to peruse from. In any case, reading in chronological order is liberatingly optional. In that sense, Vancouver Exposed is like being able to wander willy-nilly in a museum without inviting judgement for not given contemporary art a long enough once-over. Should one feel the need to adhere to chronological reading, however, the six sections are conveniently divided in neighbourhoods.

In Coupland’s City of Glass, he writes that:

For the price of a one-bedroom Kleenex box in Vancouver, you can buy a five-bedroom stone house with an acre of land anywhere else in Canada. If the conversation is ever lulling with a Vancouverite, bring up the subject of real estate and sit back to watch the conversation go on autopilot. And for anybody who’s ever tried renting anything halfway decent in Vancouver, the only way to pay the rent is to start a marijuana grow-op (p. 103).

Coupland wrote those words in 2000. In many ways, it’s downright impossible to talk about Vancouver without at least briefly fixating on the real estate prices. In her most recent novel, Consent, Annabel Lyon uses Vancouver as an adjective: “Fen, Saskia’s realtor, sold the family home a million over asking. That was Vancouver for you” (p. 186). Simply put, Vancouver is fraught with unaffordability and Vancouverites are helpless to resist its conversational magnetism.

In Vancouver Exposed, Lazarus writes that “In 1909, hundreds of Vancouver’s richest citizens lined up on both sides of Granville Street and for more than four blocks along West Hastings Street to buy lots in Shaughnessy Heights — which just goes to show that real estate speculation has always been a Vancouver sport. As a condition of sale, all homes had to cost a minimum of $6,000 — six times the price of an average house at the time” (p. 22). In other words, Shaughnessy has always been Shaughnessy, i.e. Vancouver.

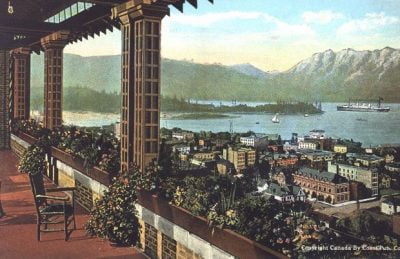

Accompanying Lazarus’s prose is a wonderful photograph that resembles a film still; people are donning hats; there is one umbrella, naturally; a bicycle, and a queue that looks like it could be for the Louvre. I’ve always thought Vancouver’s mainstream desirability was a modern trend; however, Lazarus decimates that impression. As I sometimes quip in despair, the best way to own real estate in Vancouver is to inherit it.

In Pitch Perfect 2, an outrageously popular musical comedy film, Flo, a Guatemalan afraid of being deported, finds Denmark — purportedly the happiest place in the world — to be dismally rainy and says, “Why would anyone ever leave America?” with complete sincerity. With just as much sincerity, Fat Amy, an Australian, replies pithily: “Culture, design, history.”

In many ways, the apparent youth of Vancouver can cynically invite similar criticisms, like Coupland’s:

Vancouver has a few really good buildings and a few kind of okay buildings, but mostly it’s a city of (and it really depresses me to say this) indifferent and bad buildings. The bad buildings are no accident…. Vancouver is a city of scenery. It coasts on its scenery quite shamelessly, and many builders take advantage of our love of mountain views to build charmless concrete dumps — and when you call them on it, they say, “Oh, but I didn’t want to draw attention away from the beautiful view.” Yeah, right. Many Vancouverites carry around mental detonators and, as they walk around the city, eliminate eyesore after eyesore (p. 98).

As far as I was concerned, Vancouver has Central Library, almost indisputably our most architecturally potent building; I’d even testify that it’s world-class and therein ends my pathetic defence. I largely agree with Coupland’s semi-affectionate indictment. But hang on a minute — what about the second Hotel Vancouver, which opened in 1916? It’s beautiful, in a quaint way, aptly described by Lazarus as having “looked a bit like a giant wedding cake carved out of stone” (p. 26). It’s an accurate simile. Although Lazarus does not crucify Vancouver as harshly as she could, she does write that “The old hotel was so well built that it took ten months and nearly $1 million to demolish, and instead of providing much-needed rental housing, the site became a parking lot for the next two decades” (p. 28). While not maximally explicit, Lazarus’s judgement is clear and necessary. It’s not hard to guess that destruction was never in the blueprint for the second Hotel Vancouver.

In any case, Vancouver has failed its homeless and financially impoverished population long before Gregor Robertson made his remarkably optimistic and ultimately doomed promise to end homelessness in 2015 — an image that perhaps is not altogether harmonious with Vancouver’s conception of itself as a paradisiacally green, thoroughly modern utopia. Lazarus straddles these two seemingly dichotomous notions of Vancouver expertly.

Who would have guessed that “ . . . the section of Hastings Street that runs through the middle of the Downtown Eastside was known as the Hastings Great White Way after Broadway, New York City’s theatre district” (p. 79)? Lazarus writes that, “In 1913 . . . Vancouver’s theatre district included eight movie theatres, as well as live venues like the Pantages and the Empress. Over the years, the city has managed to destroy all evidence of these theatres” (p. 79). Time and time again, Lazarus’s curatorial writing reveals the recurrent theme of destruction. Culture, design, history, however vaunted, these things have got nothing on parking lots. As Lazarus writes, “it amazes me that we still have Stanley Park” (p. 172). Apparently, even Vancouver has its limits for destruction. Or does it? Lazarus writes that “developers have been trying to chip away at it for years” (p. 172). One sighs. Is nothing sacred?

Lazarus writes warmly about Judy Graves, who “had spent thirty-three years employed by the City of Vancouver, representing the marginalized and homeless residents of the Downtown Eastside” (p. 88). Along with Jim Pattison, Graves had been given the “highest honour the City of Vancouver had to give: the Freedom of the City Award” (p. 88). One might imagine a unicorn or a parachute, but the Freedom of the City Award is “a lifetime of free parking at city meters” (p. 88), a definitively car-centric reward that is intrinsically incongruous from a city as ostensibly green as Vancouver. What heightens this awkward incongruity? Pattison is one of the wealthiest people in Canada and Graves doesn’t drive. It’s a bit like awarding a key to Gramercy Park to a nature-hating socialist (not the most common combination, incidentally). Although Graves did attempt to ask for a bus pass, she was denied. It’s one of those nuggets that I’m currently classifying as objectionable things I’ve recently learned about Vancouver, thanks to Lazarus.

On a more light-hearted note, two gems I came across include an unorthodox tribute to Kingsgate Mall, which Lazarus describes as “It’s weird or wonderful, strange or quaint, creepy or quirky, but it rarely goes unnoticed. The cupola has turned the mall into a landmark, but I can’t imagine calling it a destination by any stretch of the imagination” (p. 223). She’s right, by the way, but give Kingsgate Mall a visit anyway.

My favourite addition yet in the book is Chef Chuck Currie’s Polka-Dot House, which belongs in a neighbourhood “packed full of gorgeous old heritage houses” (p. 234), i.e. a neighbourhood ripe for luxurious complaints of the NIMBY variety. In a remarkable continuity of good neighbourly judgement, Chuck Currie has “never had a single complaint” (p. 234) — frankly, what soul-barren person would think of complaining about such painterly jubilance? Although Currie’s house might look like a lively version of chickenpox, most importantly, it just has good vibes (there was no non-colloquial way for me to express that sentiment). According to Lazarus, Currie is “always coming home to find anonymous gifts on his doorstep — bowls, juice pitchers, coffee mugs — all with polka dots, of course” (p. 244). I don’t consider myself easily touched by anything besides maybe dogs, but I found myself moved by the basic decency and convivial community a polka-dot house could elicit.

The very basic decency epitomized by an exultantly polka-dotted house is conspicuously absent when it comes to the dispiritingly egregious parts of Vancouver’s multilayered history. More implicitly than explicitly, Eve Lazarus provokes this worthwhile question: how can we become the city we are pretending to be?

*

Jessica Poon is a writer, line cook, and pianist in Vancouver. She recently completed her bachelor’s degree in English literature at the University of British Columbia. Visit her website here. Editor’s note: Jessica Poon has also reviewed books by Annabel Lyon, Monika Hibbs, Grant Hayter-Menzies, and Wayson Choy for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#985 Open scenery, hidden history”

Great articles again Eve! For all the years I lived in Vancouver (30 years approx.) and studied B.C. and Vancouver history in senior high school, there is much I didn’t know — and probably just as much I have forgotten.