#931 Carr, captivity, creativity

Woo, The Monkey Who Inspired Emily Carr: A Biography

by Grant Hayter-Menzies, with a foreword by Anita Kunz

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2019

$9.99 / 9781771622141

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

*

What, ultimately, does a statue represent? A statue is allegory at its most literal. A statue can never be the very person it hopes to represent, a representation doubtless filtered through a window of interpretation. For the most part, statues intend to speak for the vox populi, which is precisely why so many ostensibly illustrious statues are presently losing their appeal. A statue of a person says: this person — almost invariably a man — is worth admiring. And so, what if a person is worth admiring, but does not have a statue? Is admiration for a person without a statue foolhardy, then?

What, ultimately, does a statue represent? A statue is allegory at its most literal. A statue can never be the very person it hopes to represent, a representation doubtless filtered through a window of interpretation. For the most part, statues intend to speak for the vox populi, which is precisely why so many ostensibly illustrious statues are presently losing their appeal. A statue of a person says: this person — almost invariably a man — is worth admiring. And so, what if a person is worth admiring, but does not have a statue? Is admiration for a person without a statue foolhardy, then?

Of course not. Grant Hayter-Menzies observes that the statue of Emily Carr on Victoria’s Inner Harbour, unveiled in 2010 opposite the BC Legislature, was long overdue. When it comes to ambivalently unethical animal ownership there are, seemingly, two perspectives: if the owner is a man like Salvador Dali, who famously owned an ocelot, it’s de rigueur, a matter of eccentricity; if the owner is a woman like Emily Carr or Frida Kahlo, colloquially speaking, she is crazy. As Hayter-Menzies writes, “Few male artists, to my knowledge, are given the same treatment because of the pets they love. When was the last time you read a “crazy cat lady” (or dog lady) send up of Charles Dickens, or Pablo Picasso, or Richard Wagner? It seemed to me only women were judged negatively by the kinds and numbers of pets they included in their private lives” (p. 38).

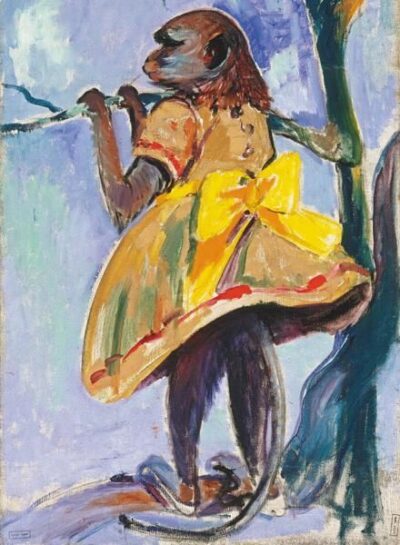

I could not have said it better myself. Indisputably, Emily Carr was an artist of lasting significance. How much of her output, however, is in debt to her pet monkey, Woo? Is great art worth a monkey’s compromised livelihood? Is exotic pet ownership less unethical if there is mutualistic affection? Can the ownership of an exotic pet be preferable to the undesirable alternatives? The answer to these questions, like all viable questions, is not necessarily straightforward, let alone satisfyingly answered; however, Hayter-Menzies’s account is nuanced, empathetic, and never unequivocally judgmental. Certainly, he understands empirically the emotional and artistic impact of pet ownership, with his own dog Freddy’s “soft brown eyes looking up at mine, when, head in hands, I straightened up to begin the struggle all over again” (p. 39). Stereotypical cats notwithstanding, the obviously asymmetrical power difference between an owner and animal lends itself to a glimpse of being, if not a deity, then a person received with seemingly disproportionate admiration, e.g. by your typical dog. At best, this asymmetry inspires the owner to live up to that disproportionate admiration. Instead of Be the change you want to see in the world, perhaps it ought to be: be the person your pet thinks you are.

Emily Carr, previously afraid of monkeys, deliberately put herself in their presence to conquer her fear. As a long-standing screamer toward spiders, I admire the tenacity of her self-prescribed exposure therapy more than I can say. In literally facing her fears, Carr wrote, “When my fear of monkeys went . . . my fear of darkness went also” (p. 48). Were monkeys and darkness inexplicably equivalent in Carr’s mind, or did confronting one fear have the domino effect of conveniently vanquishing another? I don’t know, but I was intrigued.

Meeting Woo at Lucy Cowie’s pet shop in Victoria was more serendipitous, however, than intentional exotic pet ownership. Hayter-Menzies suggests that, however unethical or problematic, Carr’s ownership of Woo was still preferable to other alternatives and that Carr perceived herself as not merely owning, but rescuing Woo. He alludes to Carr’s empathetic nature when he writes that, “Mrs. Cowie recommended the monkey to Carr, evidently seeing in her anxious features the chance of an easy sale” (p. 48). This rescue, of course, was still a transaction.

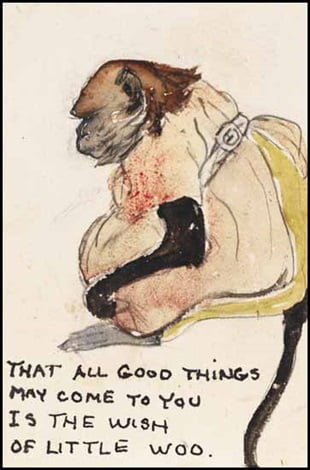

Hayter-Menzies’s depiction of Woo could be described as vaguely anthropomorphic, but that would be too easy and altogether inaccurate. The interior state of an animal cannot easily be comprehensible in quantitative terms; but that does not mean that an educated guess, rooted in empathy, is not a worthwhile endeavour. If Carr described Woo in a manner not unlike that of a person, it is because Woo herself is uncannily similar to a human and yet, irrefutably a monkey whose kinship with humans – Woo preferred them to monkeys, perhaps owing to having been tormented by bigger monkeys at Lucy Cowie’s pet store – is, in fact, also due to her unlikeness. For example, Hayter-Menzies writes, “Woo was allowed to discard all such silly human etiquette associated with receiving gifts. When she did not care for what she found in her shredded stocking, Woo simply threw it aside ‘with a grunt of scorn,’ much to the sympathetic delight of the children. Woo’s freedom to do whatever she felt like doing provided a vicarious thrill in a world of man-made restrictions on all-too-human behavioural urges” (p. 68). In many ways, Woo is like a person who has banished a corset off their id, wholly unconcerned with the etiquette of post-Victorian times, or really, any etiquette at all.

Woo is attention-hungry, such that Hayter-Menzies suggests that she intentionally poisons herself with paint to receive Carr’s affections. In other words, Woo is not an unintelligent animal destined to repeat her foibles and not to learn from them; rather, she has learned that when she is under duress, she will receive the attention she so craves – through a rational incident of self-poisoning.

Statements beginning with “Humans are the only species that,… ” from using tools to language, seem inevitably doomed for future scientific ridicule, but I will proceed anyway: humans are the only species with such flagrantly arrogant convictions of their especial capabilities. Such convictions make exotic pet ownership more understandable, if not ethically palatable. Although Woo was beloved and had no shortage of human company, as well as a remarkably affinity for Ginger Pop, one of Carr’s dogs, she still spent an undue amount of time being chained in walled rooms antithetical to her natural environment. Of course, Woo had been removed from her natural environment at an early age and Carr’s home was doubtless preferable to Cowie’s pet shop.

Hayter-Menzies concedes the difficulty of “try[ing] to get inside the mind of an animal and learn about what it has endured. An animal’s experience can be pondered, guessed at and put to the methodical determinations of science. We will never know; they will never tell us” (p. 49). He quotes Virginia Woolf: “But what is ‘oneself?’ ” . . . “Is it the thing people see? Or is it the thing one is?” (p. 41). In these two questions are more implicit questions: how much overlap is there between what is perceived and what is real?

Emily Carr’s tenure as a landlady is perhaps not as well-known as her mythic notoriety of pushing her menagerie of pet animals in a baby stroller, but it characterized a great deal of her life. While she often found her tenants contentious, she also perceived they were an obstruction to her artistic productivity, somewhat like a teacher of creative writing who no longer has time to write. A respectable day job — or a day job without respectability — often becomes a parasite to creative output, as Hayter-Menzies reports:

Carr’s problem as an artist was not so much that tenants got in her way, any more than artists or writers who work jobs waiting tables or pushing papers around desks are entirely justified in blaming their need to make a living for their lack of making art. Years later, when she . . . left behind landladying for good, Carr quixotically professed to miss it, which is like saying she pined for all the stress, worry and interruption that had faced her on a daily basis. What she missed was the battle waged daily to find the time she thought she needed for her art — the opponent against which, with an irony Carr no doubt appreciated, she had to rage in order to dream more deeply more courageously, into the thinking and making of art (p. 74).

I found myself uncomfortably relating to this, insofar as my formerly steady job as a line cook became recognizably precarious during the onset of Covid-19. And then I thought: I’ll be writing all the time now! This is a secular blessing in disguise. That didn’t happen — I found myself missing the ache of standing for eight hours straight; I read more brilliant people’s written words; I found myself wanting to hold a knife and cut stupendous amounts of food, something I could never reproduce at home; I longed for the consistent, effortless manufacturing of anecdotes and complaints about my job. In short, I needed to feel stymied to produce. Of course, Carr had a tendency to embellish her artistic inactivity; generally she was always more productive than she felt she was.

I was at the Chapultepec Zoo in Mexico City last December, embarrassingly giddy to see animals I would otherwise not be able to see. I knew I was supposed to feel ethical outrage, but I was just excited for the veritable panoply of animals. Then I came upon a solitary mandrill sitting head down, looking at his hands. The mandrill was adjacent to spider monkeys actively seeking money — they were positively clamouring for shiny coins to satisfy their inner magpies. The spider monkeys struck me as a crude, panhandling version of Wall Street traders in their skill at embracing avarice; they had done so communally. They were doing their best to relish the objectionable. But the mandrill — I felt certain that it knew sadness. What I saw was sadness. I didn’t think I was only projecting, either. I wished the mandrill would solicit something I could give it, like the spider monkeys, but the mandrill hardly moved.

Hayter-Menzies had a related experience:

When I took my cousin to a zoo, so many years later as an adult, I did so concealing at first how uncomfortable I was. . . . But when we came to the monkey cage, I no longer had dominion over my own emotions. It started with the squealing of the children, scattered everywhere, pressed against the bars. I recognized the same look in the eyes of the capuchins, who sat tensely on branches and rocks that I’d seen at the circus in the gaze of an elephant. It’s a look remarkably human, actually. It is frustration, it is anxiety, both of which were easy to understand in creatures attempting to eat their midday meal under the onslaught of human curiosity. . . . Sometimes, as I came to see, it isn’t merely the captivity that is so degrading and harmful. It’s how this captivity prompts humans to act . . . when they experience it — to treat the captive animal as some sort of living trophy (pp. 147-148).

Better a living trophy than a dispensable endangered species unfortunate enough to live in a place populous with humans dead-set on deforestation and destruction, one might opine; but surely we can do better.

Hayter-Menzies is consistently empathetic. When he is judgmental, he backtracks with nuance. When Woo is given to the Stanley Park Zoo, stripped of his beloved owner, Hayter-Menzies admits to initially not even having considered the anguish Carr experienced in being deprived of Woo. He was singularly focused on Woo’s mistreatment and premature death in reprehensible captivity — one year after his separation from Carr — but Carr doubtless suffered grievously as well.

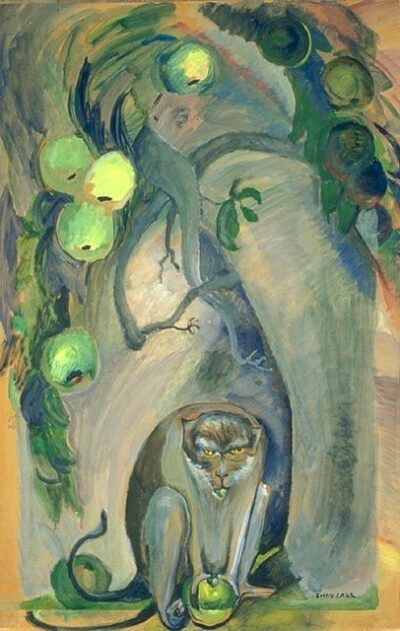

It is impossible to quantify Woo’s contribution to Emily Carr’s artistic output, but if we wanted to try, we could look at Carr’s final and arresting portrait of Woo, “perhaps unfinished (as may be indicated by the change of position of the tail)” (p. ix). He looks more menacing than friendly and holds a green apple, almost as if he is saying: See me for who I really am.

*

Jessica Poon is a writer, line cook, and pianist in Vancouver. She recently completed her bachelor’s degree in English literature from the University of British Columbia. Visit her website here. She has recently reviewed Wayson Choy’s Paper Shadows: A Chinatown Childhood: A Memoir of a Past Lost and Found, for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “#931 Carr, captivity, creativity”

I’m pleased and touched. Thank you for this beautiful review, and for seeing what I intended when I wrote the book.

Thank you, Grant. Jessica Poon brings out the best in the remarkable pairing of Woo and Emily. This is surely BC’s greatest pet story!