#969 Piquing interest in Purdy

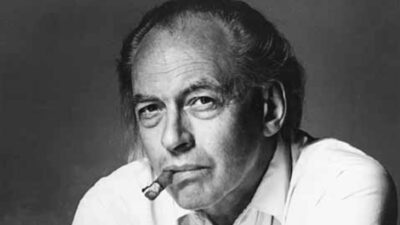

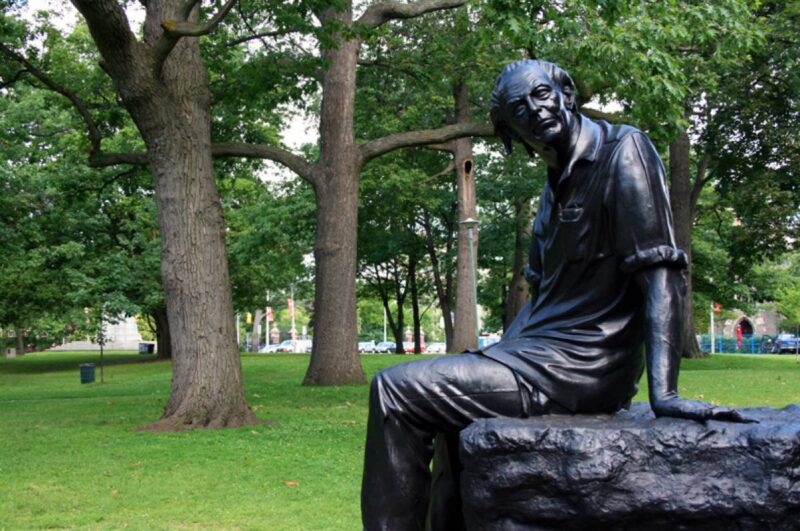

An Echo in the Mountains: Al Purdy after a Century

by Nicholas Bradley (editor)

Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020

$34.95 / 9780228003373

Reviewed by Sheldon Goldfarb

*

“Purdy,” I say. “Al Purdy. Have you heard of him?”

“Purdy,” I say. “Al Purdy. Have you heard of him?”

“You mean like the chocolates?”

She is probably joking.

I am asking people I know outside the academic poetry field what they think of Al Purdy, the quintessential Canadian poet, as he used to be called, but is he even remembered now?

By academics, certainly, the people who have contributed to Nicholas Bradley’s book. Some even seem back in the mode of celebrating the Voice of the Land, as he also used to be called, a Canadian aborigine, as the even more forgotten Louis Dudek once called him: a highly ironic, if metaphorical description, given that Purdy is now one of those dead white males imposing his colonial views on the Indigenous – at least that’s the view in some quarters.

But enough of chocolates. Let’s begin with salad. Nicholas Bradley’s book must be the only book of its kind that begins with salad. A dinner of scholars. Bradley talks of Purdy. It’s a century since his birth; time to celebrate him, or at least analyze his legacy. My dear boy, sniffs a visiting international type, you have to wait till a century after his death, not his birth.

That would take us to the year 2100. Perhaps I should hold off this review until then. Perhaps Professor Bradley of the University of Victoria should have waited. But the book is here, a new evaluation of Purdy, the poet of Ontario who also spent time in British Columbia and wrote of the Haida and visited Malcolm Lowry in Dollarton. How much was he of British Columbia and how much of Ontario? Not to mention the Arctic. But for that we would need a biography, and there is no biography, as several of the contributors mention.

We get wisps of information about him. His father died when he was only two, his grandfather when he was 12. One of the best essays in the book is about his poem about his grandfather, seeing in it a move towards connecting to lost loved ones, a universal theme – though universality is in bad odour nowadays; it means an imposition of values on others, or Others, a threat to diversity. Some of the essays talk like that and see in Purdy only a chance to make a point about colonialism. But the meat of the book is in the essay on the grandfather poem and in another on the striking poem, “House Guest,” with more universalizing about the nature of friendship and quarrelling: is the one inextricably bound up with the other?

Then if you want potatoes you can do worse than look at the editor’s introduction. If a book can be said to go fruitfully beyond its subject, the introduction is where this book does that, conjuring up the whole history of Canadian literature, at least since the glory days of literary nationalism in Canada’s centennial decade, and letting us see just how much things have changed since Expo 67, the Canada Council, and the rise of Canadian identity.

Is there a Canadian identity? And could one poet embody it? A poet who wrote beer brawling poems like “At the Quinte Hotel”? But he wrote other sorts of poems too, elegies for grandfathers and the disappearance of the Indigenous – but you mustn’t do that, the critics say now, the Indigenous haven’t disappeared; you mustn’t lament, you must … what? Dance on the grave of Sir John A. Macdonald, perhaps, as in one poem quoted here to contrast with Purdy’s white privileged approach.

But we don’t know the protocols yet. Professor Bradley says there are still questions to answer about who can make art out of Indigenous culture; who should be allowed to do that? Such questions.

In the meantime we can read a book like this, sampling its various dishes, learning that Purdy never wrote a love poem and hated the very word “love.” Can this be the quintessential Canadian poet? Is there no love in Canada? But how can either a country or a poet be reduced to something like that?

It stirs my archivist’s soul that Purdy has even made his way into Archivaria, the journal of the Canadian archival profession, though mostly because his papers are in such a mess, stuffed into old liquor boxes (of course). And there is textual editing too, though really do we care where the commas go? The best overall part of the book is the sense that emerges of how Purdy, Canadian literature, and Canada as a whole have changed since the days of Expo, the days of celebration and expansiveness. Now we are in the days of self-criticism, excoriation, finding Canadian nationalism not only wrong-headed, but wrong. How could we have been so naive?

It is a reversal worthy of Purdy himself, who along with his blustery exterior also had a quiet, reflective, self-questioning side, reversing himself even within a poem. I was wrong about those eggs, he says to end “House Guest,” conceding the point to his guest, though only after the guest has left. It is a sign of intimacy after quarrelling, says Eli MacLaren in his essay on the poem, and perhaps that is the best we can hope for.

So in the end after the arguments about canonization and de-canonization, the denunciation and the celebration, what do we have left? Some of the guests at the banquet want to deposit Mr. Purdy on the dust heap of settler colonialism. Others, though, suggest that there are some interesting insights to be gained from Mr. Purdy’s poetry. I was going to say some pretty poetry too, but Purdy’s development, as we learn from several of the essays, was away from prettiness, from the Romanticism of his early writings (which he dismissed as “drivel”) towards what some dismiss as characteristically Canadian flat free verse, but which others see as full of persona, of a complex personality grappling with nation and self, but mostly self, and uttering profundities about the power (or lack thereof) of poetry and about intimacy, the yearning for transcendence, and the recognition of our limitations.

Purdy once said he hoped he hadn’t wasted his time; he hoped he’d made a contribution. Only time will tell, as the visiting professor said, but perhaps there will be more than chocolates.

*

Sheldon Goldfarb is the author of The Hundred-Year Trek: A History of Student Life at UBC (Heritage House, 2017), reviewed here by Herbert Rosengarten. He has been the archivist for the UBC student society (the AMS) for more than twenty years and has also written a murder mystery and two academic books on the Victorian author William Makepeace Thackeray. His murder mystery, Remember, Remember (Bristol: UKA Press), was nominated for an Arthur Ellis crime writing award in 2005. His latest book, Sherlockian Musings: Thoughts on the Sherlock Holmes Stories (London: MX Publishing, 2019), was reviewed here by Patrick McDonagh. Originally from Montreal, Sheldon has a history degree from McGill University, a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba, and two degrees from the University of British Columbia: a PhD in English and a master’s degree in archival studies. Editor’s note: Sheldon Goldfarb has reviewed a dozen books for The Ormsby Review, most recently by Sherrill Grace, Philip Resnick, Miriam Nichols, Keith Maillard, Edwin Wong, and Rod Macleod. In 2019, he reviewed Beyond Forgetting: Celebrating 100 Years of Al Purdy, edited by Howard White and Emma Skagen.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#969 Piquing interest in Purdy”