#854 A real book about real music

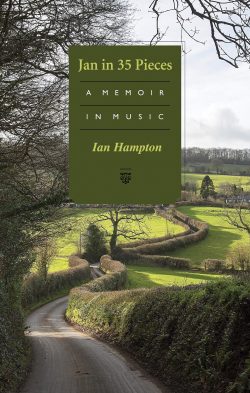

Jan in 35 Pieces: A Memoir in Music

by Ian Hampton

Erin, Ontario: Porcupine’s Quill, 2018

$24.95 / 9780889844131

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

All line drawings below by Ian Hampton

*

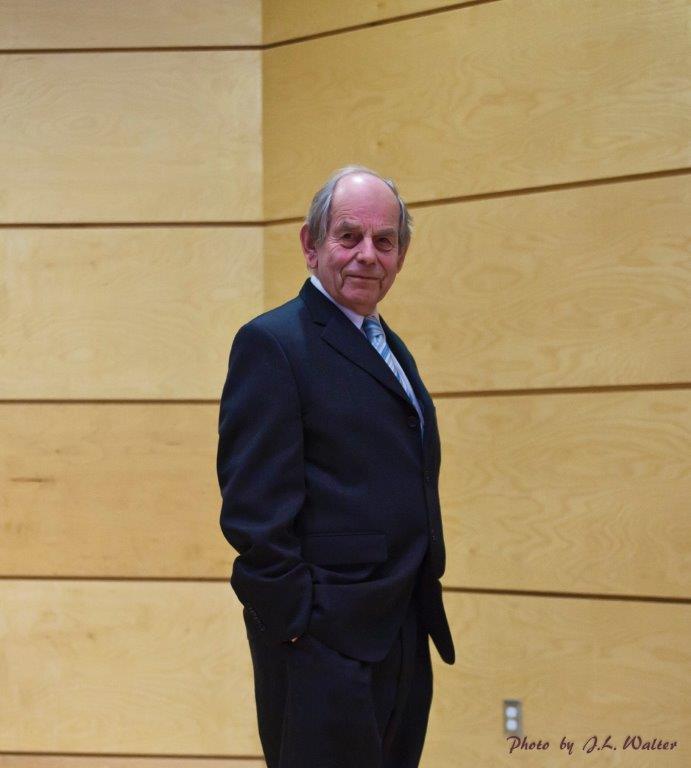

Cellist Ian Hampton is known in British Columbia and elsewhere as a distinguished musician and music educator, but his influence goes deeper and further back than he may suspect. Some forty years ago we made the daring decision to take our kids to the Sunday afternoon subscription concerts given by the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. Although they professed to prefer music groups with names like Pointed Sticks and Talking Heads (or was it Pointed Heads and Talking Sticks, and does it matter?), they — and we — became caught up in happenings on stage and sometimes off. This was nothing like listening to LPs (a.k.a. vinyls?) at home; this was a completely different experience. We may have dozed a little during the opening piece, inevitably one of the innumerable but mercifully brief Haydn symphonies. No one dozed for long; there was too much going on: real “live” music erupting from interactions among instruments, musicians, conductor, the score and the audience — an experience which cannot be replicated on Zoom.

Cellist Ian Hampton is known in British Columbia and elsewhere as a distinguished musician and music educator, but his influence goes deeper and further back than he may suspect. Some forty years ago we made the daring decision to take our kids to the Sunday afternoon subscription concerts given by the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. Although they professed to prefer music groups with names like Pointed Sticks and Talking Heads (or was it Pointed Heads and Talking Sticks, and does it matter?), they — and we — became caught up in happenings on stage and sometimes off. This was nothing like listening to LPs (a.k.a. vinyls?) at home; this was a completely different experience. We may have dozed a little during the opening piece, inevitably one of the innumerable but mercifully brief Haydn symphonies. No one dozed for long; there was too much going on: real “live” music erupting from interactions among instruments, musicians, conductor, the score and the audience — an experience which cannot be replicated on Zoom.

One Sunday Yehudi Menuhin played Bach. Another Sunday on the same stage the orchestra premiered R. Murray Schaffer’s North/White accompanied by sheets of foil and a snowmobile. Not only was music still being played, it was still being written.

We watched for the regulars to appear and empathised with their actions and reactions. Foremost among these were the first violin and concertmaster Norman Nelson and the principal cellist and author/protagonist of this book, Ian Hampton. They appear here as “Normsk” and “Jan,” pseudonyms possibly inspired by their encounters with Leopold Stokowski and his “fraudulent” Russian accent.

Hampton has structured his memoir as if it were a concert: thirty-five chapters each centred around a different piece of music and its meaning for himself and his career. An anecdote related to the piece transitions to a snippet of autobiography, more or less chronological, but chronology follows where the music leads. There is a prelude, an intermission, interludes, and a coda. The memoir is all about the music; if Jan is its protagonist, the antagonist is Music, and the setting is wherever in the world the music takes him. Beethoven is at home on D-Day at the village of Radnage in the Thames Valley, or in summer residency with the Purcell Strings Quartet at Naramata on Okanagan Lake; Mozart’s Magic Flute enchants the very young Jan at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre and the older Jan’s students at the Langley Community Music School.

Hampton writes in the third person, but unconvincingly. The reader does not for a moment forget that “Jan” is “Ian” or that “he” is really “I.” On the other hand, the device allows a certain distance not always possible in a Memoir. If Ian’s heart is broken we would not know; Jan keeps playing music. Wives and children feature only when required for context. “Marriage and touring don’t go together,” Jan remarks to his father, who replies “Ain’t that the truth, son.”

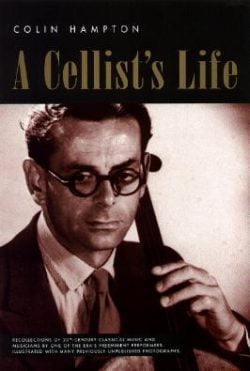

Jan’s parents get prominent roles because they too were musicians. Colin Hampton wrote his own memoir, A Cellist’s Life (2000). Hampton recalls being five, “listening to Brahms’s Quintet for the first time, sitting beside his mother. They have sneaked seats in the gods so that Jan can see the platform. To him the seats seem steeply raked. The familiar figure of his father playing the cello looks miniature. The Griller Quartet is playing a series of concerts for a festival in Bournemouth.” The “large lady playing the piano” is a great celebrity, Dame Myra Hess.

Jan’s parents get prominent roles because they too were musicians. Colin Hampton wrote his own memoir, A Cellist’s Life (2000). Hampton recalls being five, “listening to Brahms’s Quintet for the first time, sitting beside his mother. They have sneaked seats in the gods so that Jan can see the platform. To him the seats seem steeply raked. The familiar figure of his father playing the cello looks miniature. The Griller Quartet is playing a series of concerts for a festival in Bournemouth.” The “large lady playing the piano” is a great celebrity, Dame Myra Hess.

“Quartets are not competitions, they are conversations,” Colin tells him, and the child gradually acquires “a sense of the locked-in relationship of a string quartet that feeds on itself rather than relating to the real world as Jan has so far experienced it.”

Who did this child become? I have borrowed this information from the website of the Langley Community Music School, which claims Ian Hampton as Artistic Director Emeritus. Note how many times he has been filling several roles simultaneously.

Ian Hampton was born [in 1947] in London. Educated at Bedales School in Hampshire, he studied cello with Joan Dickson in Edinburgh, with William Pleeth at the Guildhall School of Music, London and with Paul Tortelier in Paris. He was a founding member of the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields and a member of the London Symphony Orchestra. He became the cellist of the Edinburgh String Quartet. Ian emigrated to Canada via Berkeley, California where he taught for a year with his father, the renowned cellist Colin Hampton. In 1966 he was appointed principal cellist of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra and also of the CBC Vancouver Chamber Orchestra. He was a founding member and cellist of the Baroque Strings of Vancouver and also the Purcell String Quartet. In 1968 he became founder and president of the Vancouver Cello Club. He taught at the University of British Columbia and was a member of the Masterpiece Piano Trio, conductor of the Nanaimo Symphony Orchestra and the Surrey Youth Orchestra. In 1979 he became principal of the Langley Community Music School and, in 1982, principal cellist of the Vancouver Opera orchestra, both positions which he continued to hold until 2000, along with his role as principal cello of the CBC Vancouver Orchestra. In 1999 Ian received the BC Arts Council award for his extraordinary contribution as a performer, teacher and administrator. In recognition of his contribution to Canadian new music, in 2009 he was named a Canadian Music Centre ambassador. In 2011 Ian was awarded an honorary doctorate from Simon Fraser University.

For “Normsk,” I excerpt from his obituary in the Victoria Times Colonist:

Richard Norman Nelson, distinguished violinist and conductor, … died peacefully on February 23, 2018 at the age of 86. Born in Dublin, Ireland, Norman had a long and full musical career that led him from Assistant Concertmaster of the Royal Philharmonic, London Symphony, and BBC Symphony orchestras and a founding member of the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields to Concertmaster of the Vancouver Symphony, founding member of the Purcell String Quartet, and Professor of Violin and Chamber Music at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. In his “retirement,” Norman founded the Sooke Philharmonic Orchestra in 1997 and directed its 60-plus devoted members until his true retirement in October 2017. He was a recipient of the Orchestras Canada Betty Webster Award, the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal and the Barbara Pentland Award of Excellence for his many years of dedicated service to Canadian music.

In his foreword, maestro Bramwell Tovey, Director Emeritus of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, refers to “that golden generation of British string players who came to the fore after the Second World War…. Although they would never have dreamt of using the term, it’s pretty clear that all of these players were from an elite group of London musicians [whose] contribution to Canadian musical life has been immeasurable.”

Perhaps because he is himself a musician, Tovey underestimates Hampton’s ability to communicate, warning that “discussions often involve tiny aspects of music — whether to play staccato or portato, whether to play pianissimo or pianississimo, whether to accelerate or maintain the tempo.” It’s all very well for the cellist who “has spent his life quibbling about such minutiae,” but “the layperson cannot begin to appreciate how much patience is required to be a member of a successful strong quartet.” I disagree. Reading this book the layperson does “begin to appreciate.” Such appreciation is enhanced if one has witnessed a string quartet in action, but I think one can “begin” even without that privilege.

Here, for instance, Hampton meditates on “the jewel of Brahms’s chamber music” — the Piano Quintet. “Jan opens the Scherzo with a foreboding low pitch, very softly. Judgment for the appropriate tempo is critical because the movement ends in imitative rhythms” — and just as you worry things are getting too high-brow, he tells you those rhythms were: “like machine-gun fire, straining at the musicians’ tendons and nerve ends,” and you know exactly what he is saying. One need not be sure what a “scherzo” is in order to sense something of what if going on or to react to the machine-gun fire. Such close but lively readings of music are an essential part of the narrative, often accompanied by deft cameo character sketches of the musicians.

In Sibelius’s 2nd Symphony, “Jan loves the warmth of the first movement with its consummating melody opening with five repeated notes, and the second movement’s suggestion of a slow walk through Finnish forests with its hint of bad weather.” On R. Murray Schafer’s 1st Quartet, Hampton writes,

The opening of Schafer’s First Quartet sounds like wasps in a jam jar, the players locked together and trying to free themselves. After the congestion of the opening, individual players examine the new landscape with thoughtful phrases – they link up loosely in a passage of moiré rhythm where one instrument enters a long, slow unison by all four players — along the way, each breaks into an improvised cadenza. As the unison gradually accelerates and gets louder, each succeeding cadenza becomes more frantic and culminates with the acoustic shock of the first cello snap.

We are not surprised to find in the following section the composer calling the cellist to consult on a work-in-progress and asking, “is it even possible to play this music?”

A Rossini sonata exhibits the “seeds of Rossini’s style, which is a quick wit and unerring sense of timing,” with “finger twisters that may unseat a musician at any moment.” On Hornby Island the Purcell String Quartet nails American composer Elliott Carter’s Second Quartet:

Sydney, the first violin, is virtuosic, taking off in flights of fancy unfettered it seems by Bryan, the second fiddle, the martinet, who with his repeated rhythms insists that the rules are observed. Phil, the violist is dolefully expressive, while Jan [on cello], the romantic, ignoring the second violin, is instructed to accelerate or decelerate on whim. Each player has his own motivic units and arrangement of intervals. Each player will earn his spurs with a cadenza and a chance to lead a movement. Carter expresses this scenario with a mathematical precision which would make demands of Einstein’s brain capacity.

In Barbara Pentland’s music room, coming to terms with her Third Quartet, they feel the composer’s “microscopic gaze.”

The book is full of little wonders: analysis of bird songs; reaction to Hoagy Carmichael’s “Stardust” aboard an ocean liner; comparison of train horns real and musically rendered from The Little Engine that Could to Arthur Honegger’s Pacific 231; the tugboat dance at Expo 86; moving the orchestra headquarters from Queen Elizabeth Theatre to the Orpheum; crossing the hinterlands of BC by ferry, being part of the first symphony to visit the Arctic, waiting on the tarmac at Nanaimo Airport because rabbits had chewed the wires to the runway lights. We learn how a young British cellist spent his National Service. We glimpse struggles with Beethoven and Bartok and overhear the informal, often crude, discussions during rehearsal. We go backstage with the Vancouver Symphony and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

Sometimes the dialogue is stilted; Hampton wants to convey the gist, but when he tries too hard we are conscious of words written rather than spoken. But that is no great matter. The book is a gem crammed with humour, history, humanity, and unexpected insights, not the least of which is a validation of the status of the West Coast in world music — beginning with Jan’s stepping off the boat at San Francisco to be “confronted by fearless, searching, unprejudiced and vibrant music activity.” That Vancouver has shared and expanded that level of activity is due in no small part to Jan/Ian and his colleagues. Soon after moving north, he bought a house, started a string quartet and a cello club, and phoned his father: “It feels like home.”

Encapsulating his role as a teacher and communicator he later wrote: “It could be Langley or Lithuania; talent can be awakened anywhere.” He is a musician “who will never retire.” At a reunion of the Purcell String Quartet, “Jan overhears a former student: ‘Those old boys can still play up a storm.'” And no wonder: all these years the “old boys” have engaged in one continuous “long-hair jam session” having as much serious fun as Danny Kaye and his accumulated jazz greats in the 1948 movie, A Song is Born. The memoir’s concert concludes with Jan listening to his own Surround Sound: a passing freighter’s “long, low horn” and the music of Henri Dutilleux: “His musical journey is not over yet; he has found an exciting new composer.”

Ian Hampton played for and with the greats of the international music world. And he played for us, a family lined up in a row in the Queen Elizabeth Theatre. We emerged from the years of the Sunday concert series as lovers of very old music and very new music and as players of piano, guitar, flute, harp, violin, and double bass. Some of the instruments are played more frequently than others, but none have been abandoned.

Jan in 35 Pieces was a finalist for the RBC Taylor Prize for Canadian nonfiction and the BC Book Prizes (Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize), and long-listed for a ForeWord Indies Book Award. Disappointingly, it is already out-of-print, perhaps a casualty of the perilous world in which independent presses operate. At time of writing Amazon still has three copies, and the book is widely available on-line. The copy in my local library has been unavailable because of the pandemic. I have been working from an e-copy — and it is definitely not the same as a real solid page-turnable book.

Yesterday the library re-opened and I went, by appointment, to collect my “on hold” copy. I have almost finished writing the review, but I want to keep the book for a few days. It feels so good. A real book about real music.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications, including the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola (Fictive Press, 2017). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website. For The Ormsby Review she has reviewed books by Carys Cragg, Yvonne Blomer, Robert Amos, Joe Rosenblatt, Eileen Curteis, Naomi Wakan, among others.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster