#787 The everlasting Bram Stoker

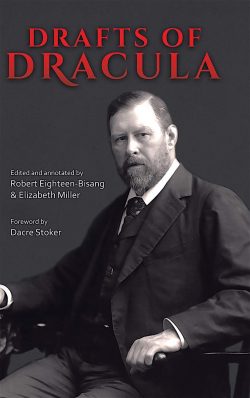

Drafts of Dracula

by Bram Stoker, edited and annotated by Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller, with a foreword by Dacre Stoker

Victoria: Tellwell Talent, 2019

[price varies] / 9780228814290

Order from your local indie bookstore or:

$30.95 / 9780228814306 hardbound @ Chapters/Indigo

$20.91 / 9780228814290 paperbound @ Chapters/Indigo

$9.95 / 9780228814313 ebook @ www.amazon.ca

Reviewed by Heather Simeney MacLeod

*

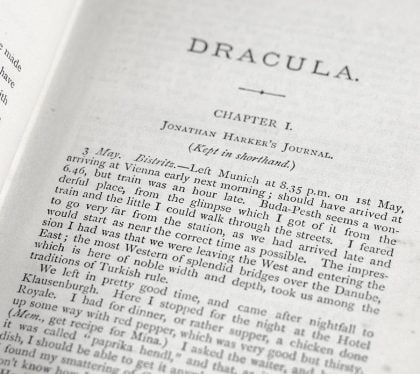

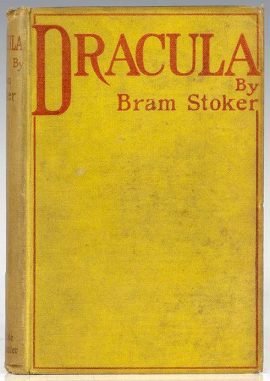

Bram Stoker’s seminal work Dracula was published in 1897. It has remained consistently in print and been translated into at least 29 languages. Stoker’s novel has inspired, and perhaps to some extent shaped popular culture across the globe. From Joel Schumacher’s The Lost Boys (1987), to Stephenie Meyer’s glittering vampires in her Twilight Series (2005-08), to Joss Whedon’s villains, heroes, and tortured victims in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (2007-11), and to Alan Ball’s coming-out-of-the-coffin living dead in HBO’s True Blood (2008-12) — they all signal Stoker’s Count Dracula.

The creation of Stoker’s Dracula, a pivotal work of horror in English, remained a mystery until 1972 when Raymond McNally and Radu Florescu, quite by chance, stumbled over Stoker’s Notes in Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum and Library. At the time, McNally and Florescu were looking for a manuscript connected to the historical figure Vlad the Impaler. Until their unexpected discovery, Stoker’s Notes were unknown. In 1975, McNally and Florescu announced their unexpected find and, in 1979, they published an annotated Dracula relying upon their reading of the Notes to provide commentary on the first several chapters of Stoker’s Dracula. It was the first peep behind Stoker’s curtain; finally, a chance to glimpse the wizard as he worked.

Certainly, scholarly work on Stoker’s supernatural narrative is as consistent as the novel’s enduring print run. However, it is the questions of a critical and a curious nature regarding Stoker’s composition that seem to have persisted and persevered: was Dracula based upon Vlad the Impaler; where did Stoker begin writing the novel; was any one castle the inspiration for Castle Dracula; was the novel influenced by the serial murders by Jack the Ripper; how much did Stoker know about Transylvania?

Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller’s Bram Stoker’s Notes for Dracula: A Facsimile Edition (McFarland, 2008) set about answering many of these questions and more. Eighteen-Bisang, of Victoria, is the foremost authority on Stoker and Dracula, while Elizabeth Miller is professor emerita of English at Memorial University of Newfoundland, Baroness of the House of Dracula, President of the Transylvanian Society of Dracula (Canadian Chapter), and Daughter of Aref (Romania).

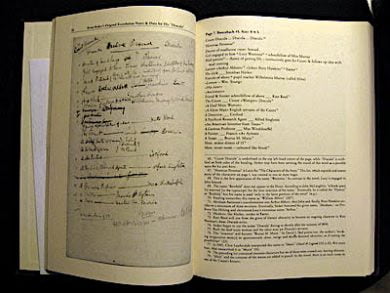

Reprinted in 2013, Bram Stoker’s Notes for Dracula was the essential reference work for any serious study of Dracula as well as being accessible to general readers. Notes for Dracula was, indeed, meticulous. It consisted of facsimile on one page while, on its opposite, Eighteen-Bisang and Miller painstakingly and thoroughly transcribed Stoker’s infamously bad handwriting. With the release of Drafts of Dracula, Eighteen-Bisang and Miller have revised and updated their previous Notes to Dracula.

Drafts of Dracula is divided into four sections: the handwritten notes about the plot, handwritten notes regarding Stoker’s research, typed research notes, and appendices. The appendices include Stoker’s timeline, his lost journal, a different direction Stoker considered taking with his novel, early adaptations from Sweden and Iceland, and an extensive index. Many of the myths that have circulated around Stoker’s Dracula, Eighteen-Bisang and Miller have addressed with unexpected outcomes, such as the notion that Stoker wrote Dracula quickly. It has often been thought and reported that Stoker conceived of and completed Dracula within a two-year time frame, but Eighteen-Bisang and Miller reveal that Stoker began to conceive of his novel as early as 1889. They write:

The first draft of Dracula opens in Transylvania and shifts to Munich, Dover, and London. It must have been written before the earliest date note of 8/3/90 (8 March 1890) on Rosenbach page #35 verso a (28), but how much earlier remains a mystery (p. 14).

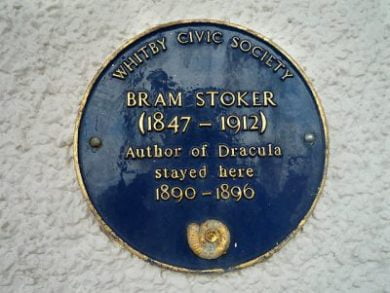

The idea that Stoker came to the notion of limited points-of-view with multiple perspectives reluctantly is inaccurate. Eighteen-Bisang and Miller clarify that Stoker was quite aware of the literary concerns of the time and was, as indicated in his earliest notes, interested in utilizing the same modernist novel techniques as his contemporaries. Though critics have known that Stoker relied upon Emily Gerard’s “Transylvanian Superstitions,” published in The Nineteenth Century (1885) for information about vampires, the Notes reveal the depth of work that Stoker undertook on his novel while holidaying in Whitby in 1890 with his family. The Count’s entrance by shipwreck may well have been conceived in Whitby, for Stoker writes: “Tonight talked with Coast Guard Wm. Petherick (. . .). Told me of various wrecks. A Russian schooner 120 tons from Black Sea ran in with all sails main-stay” (p. 116). Eighteen-Bisang and Miller address the many myths and legends that have surrounded Stoker and his novel in this detailed and thoroughly documented study.

Though most of the drafts continue to be introduced by a facsimile page, the revised version does not provide a facsimile of each page of Stoker’s notes, as their first version did. Quite surprisingly, the facsimile pages are not as important as first anticipated, for it’s the transcription and the work undertaken to unpack, decipher, and reveal Stoker’s Notes that proves most beneficial and thought-provoking. Eighteen-Bisang and Miller assert that “[t]he most important difference between Bram Stoker’s Notes on Dracula and the current volume may be the position and interpretation of the first three pages. We have decided that pages 38a, 38b and 38c are neither research notes nor a simple ‘memo.’ They constitute the earliest-know [sic] draft of Dracula” (p. xxvi).

The assertion that the Notes contain the earliest-known draft of Stoker’s Dracula is dramatic. Nonetheless, it’s The London Library appendix that provides the most startling revelation. London Library’s Director of Development, Philip Spedding, indicates that he “noticed that there was a certain amount of marginalia — crosses and lines in particular — that are very close to the references in the Notes” (quoted here, p. 275). Eighteen-Bisang and Miller indicate that following the discovery, “but before it was made public, the London Library helped us identify several titles that had eluded us when we wrote Bram Stoker’s Notes for Dracula and, mirabile dictu, was often able to specify what editions Stoker had used in his research” (p. 276). Of course, they provide a key to the annotations and an additional list of books Stoker consulted.

Drafts of Dracula continues the exceptional labour of scholarship that Eighteen-Bisang and Miller initially undertook with Notes of Dracula. The effort and indeed exertion of transcribing, annotating, and publishing the working notes of such a seminal piece of literature in English ought to be praised. Indeed, Eighteen-Bisang and Miller’s meticulous and precise scholarship reveals the construction and progression of Stoker’s Dracula. Importantly, and perhaps overlooked in the current climate of interpretation, Eighteen-Bisang and Miller don’t interpret Dracula: they illustrate how Stoker gave life to the living dead.

*

Heather Simeney MacLeod is a Métis writer and artist. She has published four collections of poetry, her plays have been performed in Canada and abroad. Two of her plays have won honorable mentions in contests in Canada and the United States. Her creative nonfiction piece, “To Discover the Various Uses of Things,” won first play in the Malahat Creative Nonfiction prize. Her visual art has been exhibited in Victoria and Yellowknife. She is currently a Lecturer at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#787 The everlasting Bram Stoker”