What influenced Jack Shadbolt?

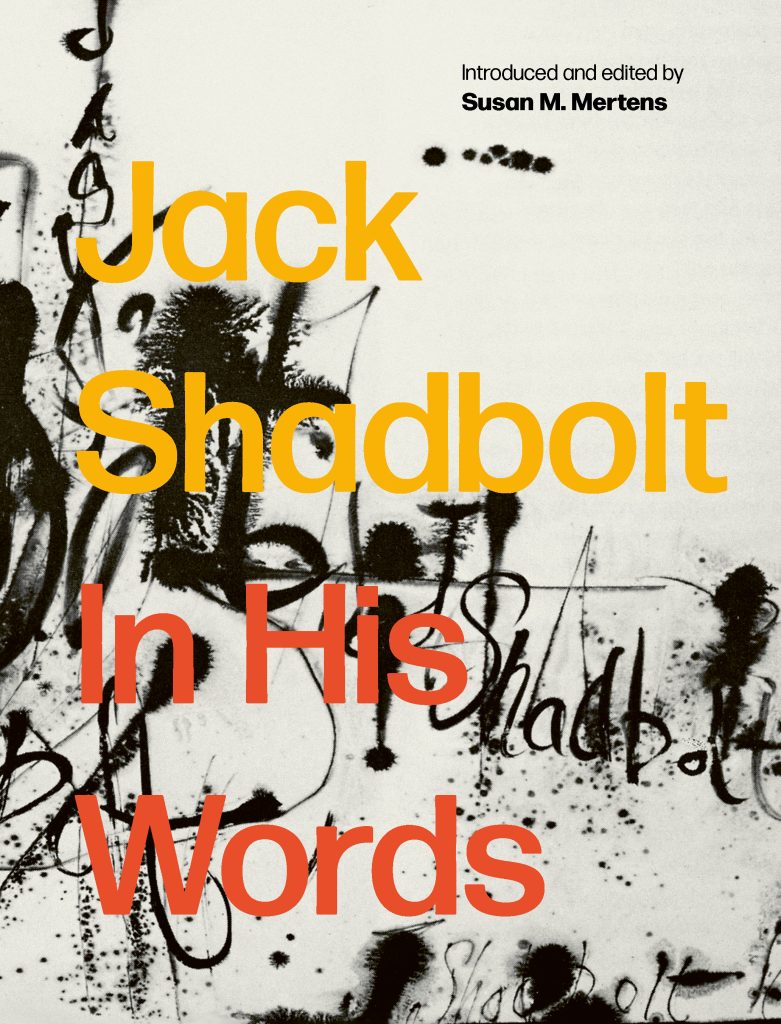

Jack Shadbolt: In His Words

by Susan M. Mertens (ed.)

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2024

$40 / 9781773272559

Reviewed by Trevor Marc Hughes

*

While working as a CBC Radio arts reporter, my least favourite part of the work was writing and voicing obituaries. I knew of reporters who would, when things were slow, write them in advance of important figures in BC actually dying. As a newcomer to the arts desk, I didn’t have that pre-written obit to rely on when Doris Shadbolt died in 2003. I knew little about her, other than a quarter-century of work with the Vancouver Art Gallery, establishing, with her husband, prolific artist Jack Shadbolt, the foundation for the visual arts in their names, and having been a great support for her husband as he furthered his creative work. I had much to learn in just a few hours.

When the opportunity came to review this title, I was reminded of that time, as a nervous arts reporter feeling great responsibility in giving listeners an impression of a woman who not only had a tremendous impact on the arts community here in Vancouver, but also supported her husband, a man whose impact on the arts in British Columbia was profound, and reached across Canada.

Susan Mertens, not unlike myself, also wrote on the subject of the arts, but for the Vancouver Sun. Her husband, Max Wyman, produced the recent title The Compassionate Imagination, which takes a good look at how the arts community of a society is crucial to democracy. Mertens has compiled a collection of Jack Shadbolt’s own writing at different times in his life and career.

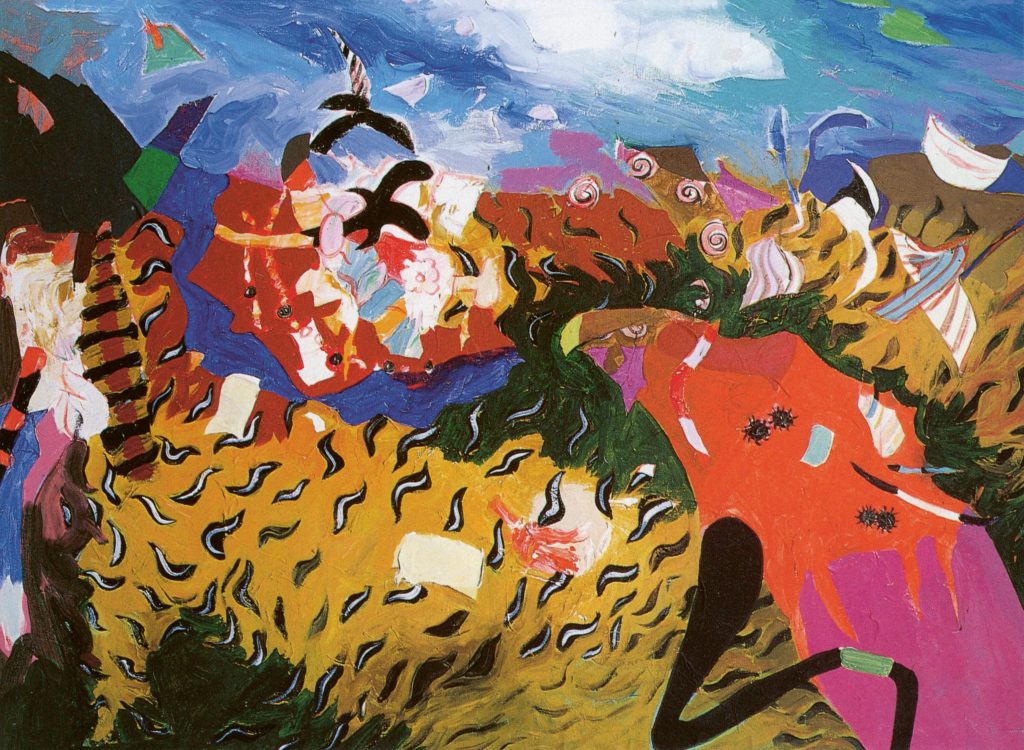

Although it is made clear in Susan Mertens’ introduction that Jack Shadbolt used Indigenous-inspired forms, I was more drawn to his influences from Europe: Dali and Picasso. Shadbolt was an immigrant to Canada from England. That he met Emily Carr as a young man seems appropriate, as the natural world would influence his work not unlike it did for her. What did Shadbolt bring from England, and how did it butt up against what he found in BC? “Nature scares the hell out of me…” Jack Shadbolt wrote. Mertens, quite appropriately, adds what Northrop Frye presented when it came to the creation of a Canadian identity: “…the conflict between the precepts of a puritan conscience and the recognition of the mindless amorality of nature.” Mertens, in her introduction, sets the stage for Jack Shadbolt’s inner conflicts, which explains for me how Shadbolt’s work features such impactful and non-harmonious imagery of nature, very much in contrast to the work of Emily Carr and Group of Seven member Lawren Harris.

I grew up in Victoria in the 1970s and 1980s. When Jack Shadbolt grew up there in the 1920s, the population seemed to be made up of “remittance people from England.” This was the result of an immigration boom. British settlers saw art as sacred, and a highbrow culture was generated, for which one young Jack Shadbolt felt unqualified. Luckily, he had a mentor in the form of Max Maynard to act as guide. But extraordinary to read that even Jack Shadbolt felt out of his element, in a time and place where even Emily Carr was seen as a maverick. “Art was largely in the hands of fashionable and well-established women,” recalled Shadbolt. This was not a place where even the cheerful poor could mix and mingle.

His later time as a student and art instructor in Vancouver would have Shadbolt run right into privilege, the snobbery of wealthy families curtailing him. But he would find connection through Charles Scott and his Vancouver School of Art instructor, and member of the Group of Seven, Fred Varley. His time in Vancouver coincided with the foundation of the Vancouver Art Gallery. He would have a correspondence with another member of the Group of Seven, Lawren Harris, and became friends with Jock MacDonald, also an instructor at the Vancouver School of Art. He had moved beyond that snobbery encountered in Victoria, and was on his own trajectory, based upon his own work and connections with accomplished artists.

But the most significant influence Shadbolt seems to have had was the place itself. “I love BC with a fervour,” he wrote enthusiastically. “It was a lifetime affair.” And even though the natural world could reduce him to quivers, his gratitude to be in this place was without bounds. “When Doris and I found this lot on the sunny slope of Capitol Hill [in Burnaby],” he once wrote with relief, “we both knew it was for good.” Even though Shadbolt felt he didn’t meet up to his own expectations, after stints in places like New York, London, and Paris, was the ultimate realization for him that the real prize was the place he called home? This ongoing struggle within himself was a revelation to me.

But also revealing was Shadbolt’s writing about his committed relationship to his wife, Doris.

“Suppertime is usually our discussion time between Doris and me,” Shadbolt wrote. “In the course of these casual discussions she often reaches a stage of great fluency, which, combined with her customary lucidity of mind, is both pleasant to behold and illuminating. She has a gift for putting things succinctly without hardly even realizing the quality of what she has said.” It was through reading this passage that I realized how important it was for the artist to have the foundation his wife provided to keep him on the rails, to allow him to produce work the way he did. His admittance that “we provoke ideas in one another” shows that artists need outside influences, muses, and do not exist in a vacuum. Shadbolt found love and admiration in her.

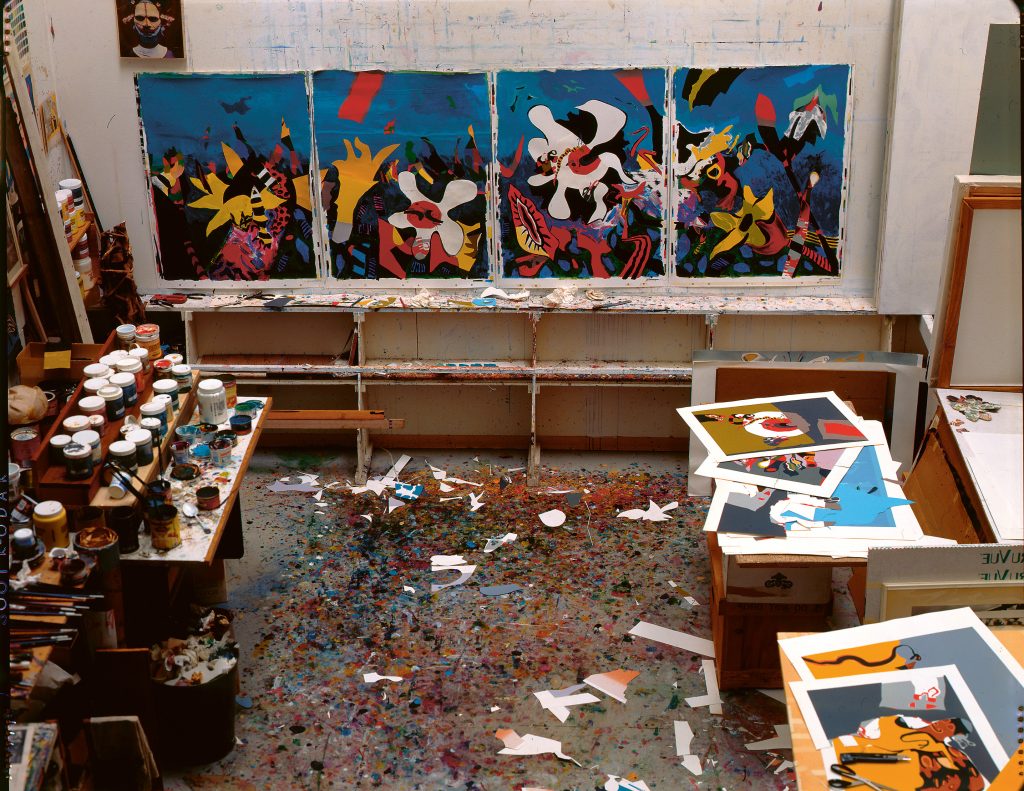

The book showcases the work that emerged as a result. From the sexual imagery of butterflies, to the confused and chaotic state of mind brought on by natural landscapes and creatures found in them, to the exploration of potential structure shown in consequential panels, Shadbolt appears to have been an artist who not only absorbed the natural world in the place called British Columbia but also attempted to describe the state of mind it created within him.

The significance of having read out Doris Shadbolt’s obituary more than twenty years ago on the airwaves has all the more significance to me now, not only to have noted the impact she had through her twenty-five years at the Vancouver Art Gallery, but how she acted as support for one of the greatest artists this place, the one that he loved to distraction, has produced.

As Jack Shadbolt ended one passage: “I lean on Doris.”

*

Trevor Marc Hughes is the author of Capturing the Summit: Hamilton Mack Laing and the Mount Logan Expedition of 1925. His newest book is The Final Spire: ‘Mystery Mountain’ Mania in the 1930s. A former arts reporter at CBC Radio, he is currently the non-fiction editor for The British Columbia Review and recently reviewed books by Richard Butler, Wade Davis, David Bird (ed.), Ian Kennedy, John Vaillant, and Peter Rowlands. He recently wrote an editorial on the subject of historic British Columbia publisher New Star Books winding down.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster