A war on knowledge

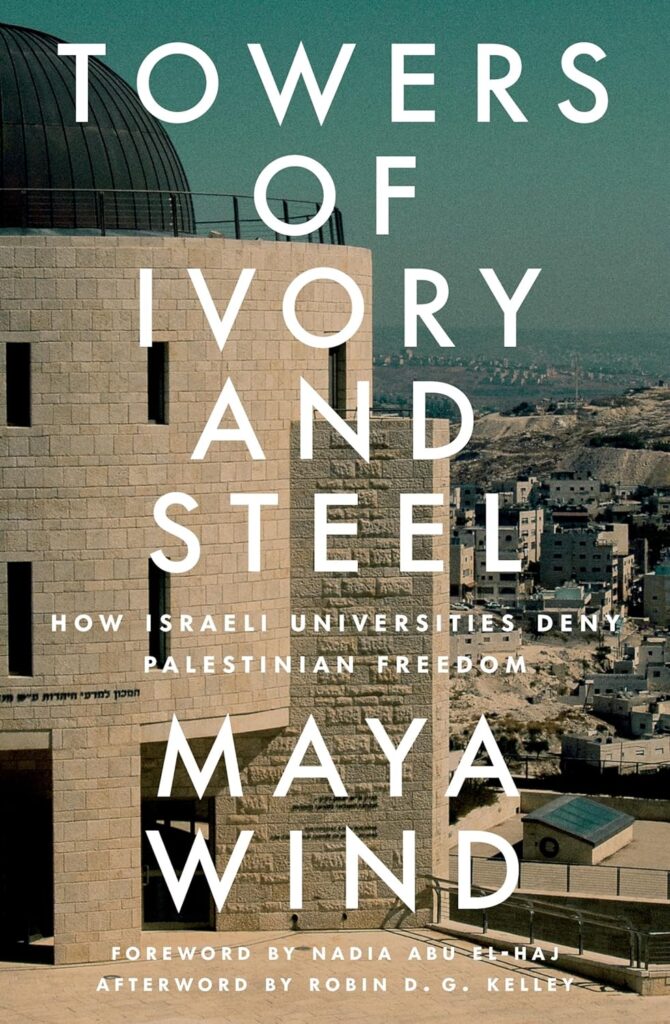

Towers of Ivory and Steel: How Israeli Universities Deny Palestinian Freedom

by Maya Wind

London: Verso, 2024

$39.95 / 9781804291740

Reviewed by Larry Hannant

*

One of the more contested aspects of the campaign urging people and states to boycott, divest from, and sanction Israel for its occupation of Palestine and its genocide of Palestinians is the call for academics worldwide to refuse to collaborate with Israeli universities and scholars.

Critics say that an academic boycott surely misses the mark by blaming people and institutions that have nothing to do with the decades-long Zionist conquest of Palestine.

Surely not, contends Maya Wind, who was a 2023-24 Killam Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia. In Towers of Ivory and Steel, Wind has written a compelling chronicle of how Israeli universities have been embedded into Zionist colonization of Palestine right from the founding of the state of Israel in 1948. This contradicts any notion that Israeli universities stand apart from a state that, especially with its unrelenting assault on Gaza, is earning a reputation as fundamentally genocidal.

Wind sets out the many ways that Israeli institutions of higher education are enlisted in Israel’s settler-colonial project. Some are strategically situated to anchor Israeli territorial expansion, often standing literally on the sites of razed Palestinian villages. Research to develop weapons of mass destruction and surveillance is commonplace in Israeli universities, which are closely coordinated with arms manufacturers and the Israeli military. All Israeli universities have tailored degree programs for the military and secret police. And the few Palestinian students who attend the universities are stifled and, through the presence of uniformed members of the Israeli military as students, roughly reminded of their people’s occupation.

Wind describes herself as a “scholar-activist,” a label that’s confirmed by her experience. A Jew who grew up in Jerusalem, she took early activist steps at age 18 when she refused to enlist in the Israeli army, for which she was jailed 40 days. Following an academic path, she completed her PhD at New York University before taking a postdoctoral fellowship at UBC.

Her scholarship investigates how settler societies and global systems of militarism and policing are sustained, with a particular focus on Israel’s occupation of Palestine and its development of weaponry and intrusive surveillance technology that it uses against Palestinians then markets abroad.

Although she didn’t originate the term, Wind describes Israeli universities as “land-grab institutions,” a take-off from the phrase “land-grant” universities common in the U.S. By applying the concept to Israeli universities, she reveals another way in which Israel is a colonial settler state in the mold of Canada, the U.S., New Zealand, and Australia, among others.

The academic integration with the land-grab agenda of Zionism, Israel’s founding ideology, began with its first universities. British conquest of Palestine during the First World War set the conditions to implement the project of establishing an exclusively-Jewish state in a land whose majority population had been Palestinian for centuries.

The first Zionist-created university in Palestine was Hebrew University, launched in 1918, immediately after the British takeover. Hebrew University was set at the strategically-chosen apex of Mt. Scopus to stake a symbolic and material claim to the entire city of Jerusalem. Later universities were similarly strategically placed. For example, the University of Haifa – built on Mount Carmel in the Galilee, the area of heaviest Palestinian population within the Israeli state as incorporated in 1948 – anchored research and planning for mitspim (lookouts), which are the nuclei of Jewish settlements built on advantageously selected hilltops throughout the Galilee.

Hebrew University was fully integrated into the battle to carve out Israel. In 1946, the Haganah, a Zionist militia, established a Science Corps, which opened bases on three university campuses, where it became central to the development and manufacture of weapons. Within two years, a Hebrew University microbiology initiative created a typhoid-dysentery bacteria for use by the Haganah.

The expertise was quickly turned to the expulsion of the Palestinians. To prevent expelled Palestinians from returning to their home villages, Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion ordered the military to poison Palestinian wells with typhoid. Thus, Israel’s premier university set the stage for a decades-long pattern of crimes against humanity and, arguably, genocide.

Another controversial issue taken up in Towers of Ivory and Steel is the state of academic freedom at Israeli universities. Understood to be the right to conduct research and publish against the grain of conventional thinking, academic freedom is regarded as one of the foundations of any principled post-secondary education system. But prominent cases illustrate that free inquiry is lacking at Israeli universities.

For example, Jewish Israeli academics who dare to challenge standard views on Israel’s history and contemporary status have been given blunt lessons in the limitations on their academic freedom. Foremost among them have been the “new historians” who, beginning in the 1980s, unearthed Israeli state documents to lay bare details of the mass expulsion and massacres of Palestinians during the 1947-48 war that created Israel. For daring to challenge the dominant narrative of Israel’s history, they were condemned as antisemites, their work assailed, and their academic appointments threatened.

Perhaps the most prominent case of academic intimidation was the persecution of a University of Haifa graduate student, Theodore Katz, whose thesis used state records and 135 lengthy personal interviews to lay bare the Israeli military’s massacre of over 200 unarmed Palestinians in the village of Tantura in May, 1948. The Tantura slaughter was part of a much broader extermination and displacement campaign that saw mass killing in dozens of villages and the expulsion of half the Palestinian population, 750,000 people.

Katz’s thesis was awarded high marks and approved by the university. But when it became public, controversy erupted. Sued for libel by some former Israeli soldiers, Katz was coerced into rescinding the findings of his work.

When the respected University of Haifa historian Ilan Pappé assessed Katz’s thesis and found it to be valid, the wolves then turned on him, with calls for his dismissal and threats against his life. Perhaps only the fact that the case became an international cause célèbre prevented Pappé from being sacked. But in the face of threats and attacks by fellow academics and the media, Pappé left the university and Israel entirely, taking a teaching post in England.

Completed before October 2023, Towers of Ivory and Steel reveals a long pattern of Israeli attacks on Palestinian universities that specialists in genocide have, since October 2023, taken to describe as “scholasticide.” In the seventeen years after 2006, when Israel formally withdrew its settlements in Gaza and imposed an illegal blockade on it, Israel attacked the two million Palestinians locked into that ghetto in five major operations. Virtually every one saw calamitous damage to Palestinian universities and killing of academics and students.

But in 2023 what had been a disgraceful multi-year campaign descended into a barbarous destruction of every university. All of Gaza’s twelve universities have been bombed and mostly destroyed. The total decimation of one briefly caught the public eye in January 2024, when the Israeli military released a video of it levelling the complex with controlled demolitions. Wrecking the university, however, came only after the Israeli army had used it as a barracks for months and pilfered all the artifacts and documents stored there.

Other evidence of scholasticide includes the killing of about 140 university professors and the razing of close to 500 primary schools. Gaza’s 625,000 school pupils have had no official classes for over one year. Thousands of them are dead, as the Israeli Maccabi soccer fans celebrated in their rampage through the streets of Amsterdam in early November, shouting “There are no schools in Gaza because there are no children left.”

Today, Gaza is ravaged as a home for 2.3 million Palestinians. The culprits in Tel Aviv have been indicted by the International Criminal Court. But also culpable is the Israeli academic infrastructure, yet the names of those criminals are nowhere on court documents. Towers of Ivory and Steel holds up a compelling indictment of them to the world.

*

Larry Hannant is the author of All My Politics Are Poetry (Victoria: Yalla Press, 2019, reviewed here by Natalie Lang). His most recent book is an edited collection titled Bucking Conservatism: Alternative Stories of Alberta in the 1960s and 1970s (Athabasca University Press, 2021). Hannant taught aspects of human rights history for years at BC universities and colleges and is engaged in writing an anti-imperialist history of human rights. He lives in Victoria. [Editor’s note: Larry Hannant has recently reviewed books by Christopher Thomson, Grand Chief Ronald M. Derrickson, David Spaner, Pitman Potter, Suchetana Chattopadhyay, and Eve Lazarus for The British Columbia Review, and has contributed three essays, ChatGPT and me, I’m not your man: Norman Bethune & women, and Letter from Victoria.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “A war on knowledge”

Thanks to author, Maya Wind, and reviewer, Larry Hannant, for adding to the body of knowledge exposing another of Israel’s ongoing crimes against Palestinians. These crimes include the early destruction of Palestinian libraries, to the recent murder of academics and destruction of schools. “Towers of Ivory and Steel documents a little known side of Israel’s subjugation of Palestinian life and culture.