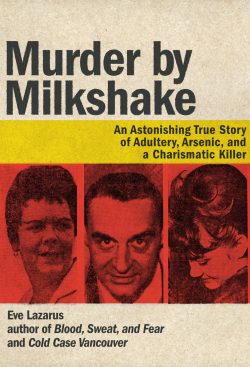

#415 Murder by Milkshake

Murder by Milkshake: An Astonishing True Story of Adultery, Arsenic, and a Charismatic Killer

by Eve Lazarus

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018

$21.95 / 9781551527468

Reviewed by Larry Hannant

First published November 6, 2018

*

True crime “may be the dominant genre of our time,” according to Globe and Mail media writer Simon Houpt. And little wonder. It’s got much going for it. The inherent mystery of a fictive whodunit is bolstered by a factual foundation that gives both writer and reader plenty of detail to sink their teeth into.

True crime “may be the dominant genre of our time,” according to Globe and Mail media writer Simon Houpt. And little wonder. It’s got much going for it. The inherent mystery of a fictive whodunit is bolstered by a factual foundation that gives both writer and reader plenty of detail to sink their teeth into.

Still, true crime puts a writer to the test. Since the events actually happened, an internet search will quickly yield the conclusion that the foul deed was done by the Plutocrat in the White House with a Tweet. Case closed.

So the true crime writer can’t entice the reader down dead-end paths, dangle false clues, or introduce clearly-guilty suspects who turn out to be innocent.

So how’s the beleaguered writer to hold the reader’s attention?

The question was answered in 1752 by the great French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher Voltaire: “My secret is to force the reader to wonder: Will Philip V ascend the throne?” As it turned out, Philip would, even if the prospect of a member of the French royal family taking power in Spain would provoke the War of the Spanish Succession that raged through Europe and spread carnage even into the Americas from 1700 to 1713. Consumed by suspense as they undoubtedly were, Voltaire’s readers already knew the answer to the dilemma he posed. Thus advised, successful true crime writers since the 18th century have crafted their words to make the inevitable seem uncertain.

Eve Lazarus takes on this task in Murder by Milkshake, an examination not just of a bizarre case of poisoning in mid-1960s Vancouver, but also of the gawky city in which it took place. The Vancouver Lazarus sketches was an unsophisticated adolescent whose beauty had not yet become iconic and for whom culture was still dangerous terrain. In 1962, for instance, the edgy U.S. comedian-social commentator Lenny Bruce performed once at Isy’s Supper Club. The redoubtable journalist Jack Wasserman attacked the show, and the city’s licensing boss threatened to close the club. Bruce was sent packing.

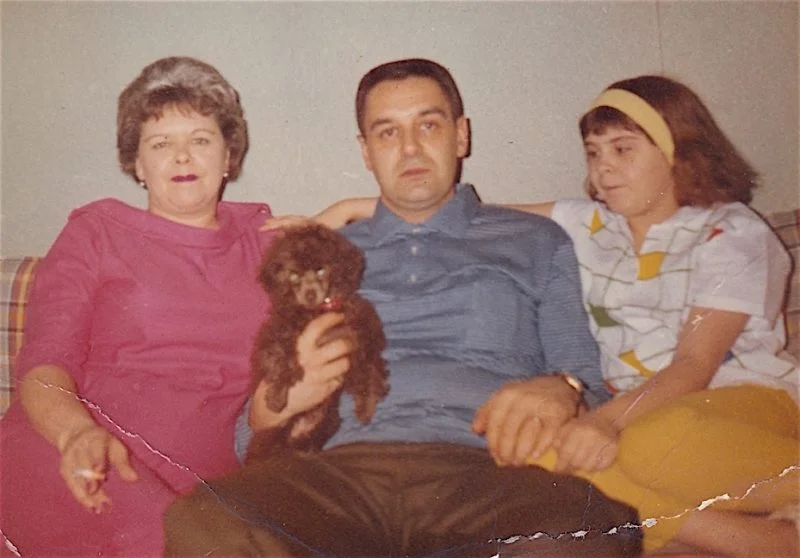

Lazarus deftly weaves her main characters into this still-conservative social milieu. Rene Castellani was an ambitious radio personality with a flair for self-promotion who had reached the cusp of success after a chequered career repairing washing machines and managing out-of-the-way hotels. He was riding high in what was the heyday of the radio boom of the early 1960s at CKNW, which a news reporter described as “the most promotion-minded station you could imagine.” He excelled at inventing on-air and street-level personas like Klatu from Outer Space and the Maharaja of Aleebaba who had credulous Vancouverites believing in alien invasions and Indian potentates intent on buying up British Columbia.

Esther Castellani, married to Rene since 1946, worked part time at a children’s store, assumed most of the tasks to raise their young daughter, Jeannine, loved nothing more than a White Spot meal of a burger, fries and a milkshake, and repented for days on failed diets of cottage cheese.

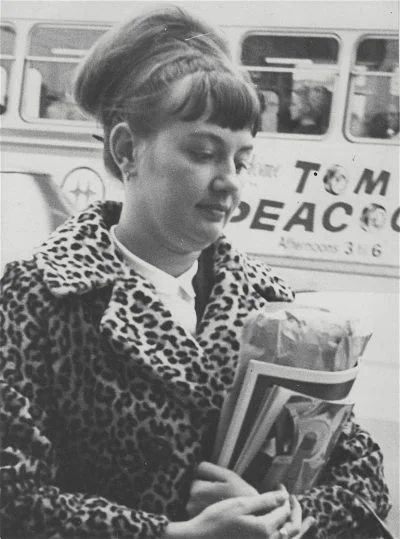

Lolly Miller was a widow fifteen years younger than Esther who worked as a receptionist at CKNW. Her birth name was Adelaide, but “Lolly the Dolly” was the name that stuck at the radio station.

By 1964, rumours of an adulterous affair between the ebullient Rene and Lolly were rife, such that CKNW management warned them about the controversy. In May 1965, Lolly was fired over the issue, despite being the sole parent for her six-year-old son. Rene was spared, in part because his wife was already seriously ill, suffering a combination of ailments that baffled doctors.

Before the wide-ranging 1969 reform of the divorce, abortion, and birth control laws that gave Pierre Trudeau an early reputation as a progressive, the only grounds for divorce in Canada was adultery, and the divorce itself had to be by mutual consent. That agreement was not likely to occur between Rene and Esther.

Bring on more milkshakes, laced, as it turned out, with arsenic. But no one suspected that on 11 July 1965, when Esther died after more than six agonizing weeks at Vancouver General Hospital. Three days later, one day after Esther’s funeral, Rene, Lolly and their two children drove off in the CKNW car for a holiday in Disneyland.

What killed the perfect crime was the dogged determination of Dr. Bernard Moscovitch, the internist who had cared for Esther. His persistence, augmented by two astute forensic specialists and diligent work by two Vancouver police detectives, produced the cause of death and, still under the kitchen sink at the Castellani home, the source of the arsenic, weed killer. Rene was arrested, charged and convicted of murder. Sentenced to death, his punishment was commuted to life in prison less than two weeks before he was due to hang.

An experienced crime writer, Lazarus lays out the case in a capable fashion, although two lengthy chapters of background mean that the story doesn’t begin to get some wind until page 40. And considering her list of five previous books of true crime and historical mysteries, her account of the trial of Rene comes across as lacking the element of suspense that Voltaire argued was essential. In a single paragraph of 75 words, for instance, she skims over the defence attorney’s plea for acquittal, the jury’s deliberations and guilty verdict, and the judge’s imposition of the death penalty. What might have been played for drama comes across as matter of fact.

Having passed over the trial, Lazarus follows up with an extended assessment of the impact of the trauma on Jeannine Castellani, the couple’s daughter. Understandably troubled by the loss of her mother and the realization of her father’s crime and his ruthless manipulation of her, Jeannine struggled for years to address the carnage that consumed her youth.

This focus on the living victim could be especially appealing to women readers, who, again according to the Globe and Mail’s Simon Houpt, make up 80 percent of the true crime audience. The focus on Jeannine also reveals a laudable effort to minimize the sense of exploitation that is felt by some survivors of actual crimes who are featured later in books and films.

As a social history, Murder by Milkshake gives us a portrait of a city still on the brink of finding itself, far from today’s shimmering metropolis that’s consistently among the top ten of the world’s most livable cities. That snapshot of a city populated by ambitious, struggling people gives the book special merit.

*

A history professor and an award-winning book author and website contributor, Larry Hannant presents history in a variety of formats. He’s the author or editor of three books, including The Politics of Passion: Norman Bethune’s Writing and Art (1998), which won the Robert S. Kenny Prize in Left/Labour Studies. His forthcoming book is an edited collection titled Bucking Conservatism: Alternative Stories of Alberta in the 1960s and 1970s (2019). The award-winning website Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History includes two sections from him. In addition to non-fiction, he’s published poetry, creative non-fiction, short stories, and articles in a number of magazines and newspapers. He’s an adjunct associate professor in the Department of History at the University of Victoria.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “#415 Murder by Milkshake”

Comments are closed.