‘Cultural appreciation versus cultural appropriation’

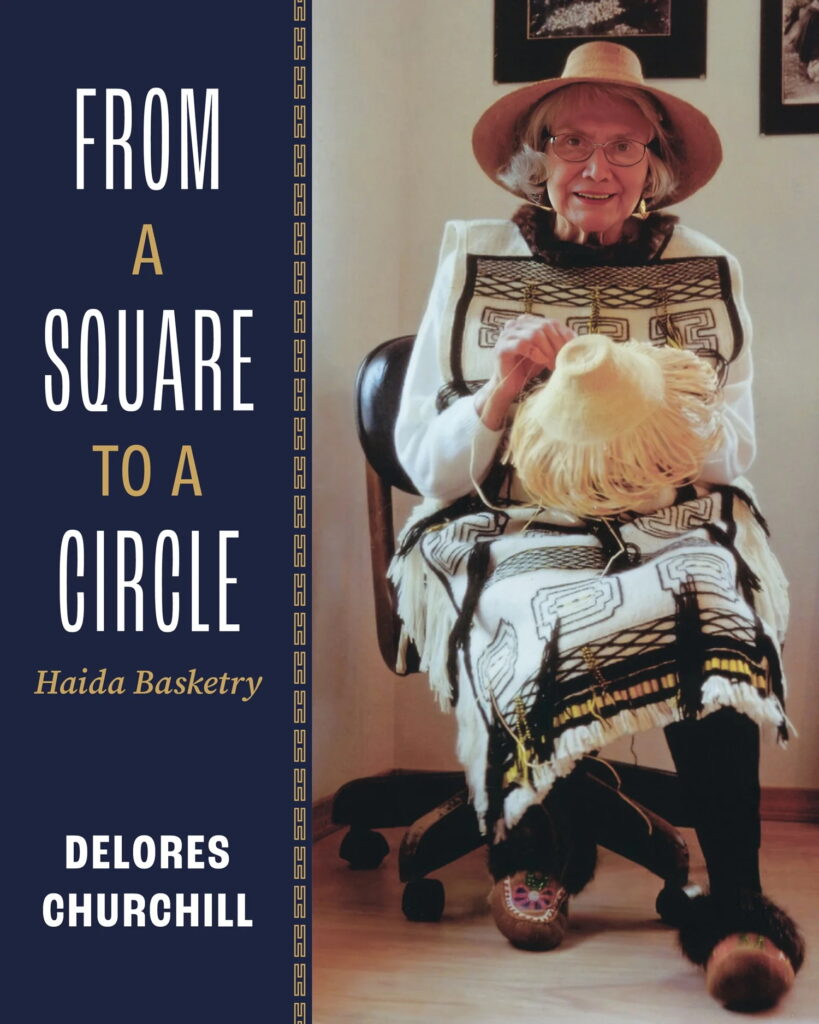

From A Square to A Circle: Haida Basketry

by Ilskyalas, Delores Churchill

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2024

$34.95 / 9781990776854

Reviewed by Sharon Fortney,

Senior Curator of Indigenous Collections, Engagement and Repatriation, Museum of Vancouver

*

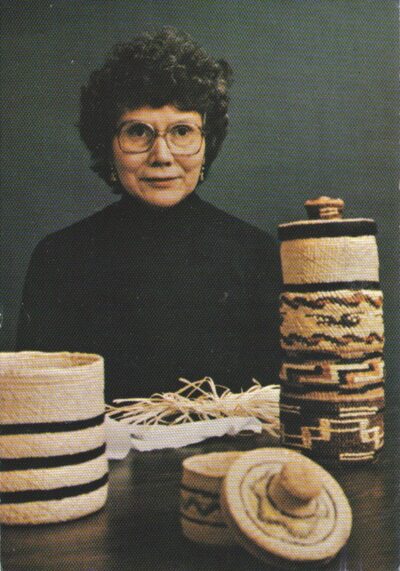

In some ways the title of this book, “From A Square to A Circle: Haida Basketry,” is misleading as this book is about so much more than Haida basketry. It is rich with traditional knowledge and cultural protocol and is truly a gift to the reader. The book begins with a proper introduction to Delores Churchill, identifying her clan and family memberships and the many people who shared their teachings with her on her journey to become a master weaver. The foreword also acknowledges those who are carrying on these teachings in her own family – among them her sibling’s children and Delores’s grandchildren.

In the opening chapters “My Teachers” and “My Beginnings,” Delores’s introduces her mother Ilst’ayaa (Selena Victoria Harris Adams Petrovich) as her primary mentor but also pays respect to her other teachers from the Haida, Ts’mysen and Tlingit communities. Although early on she acknowledges that “traditionally, family members teach family members how to weave,” by writing this book she is modeling her mother’s decision to share these teachings more widely to ensure that they continue to thrive. By doing so, the well-being of the larger Haida community is given priority – it cannot be stressed enough how truly generous a gift this book is.

Throughout this book, the reader is taught that Yah’guudang (respect) should guide all aspects of daily living, and as the book progresses, we see more specifically how this practice should be carried out while one is out on the land for harvesting and when materials are being processed for basketry. Lessons on different barks and roots are provided. Delores shares details about where and when to harvest and reminds the reader that the gifts of the natural world are just that – gifts, to be treated with respect, or they may be taken away. We also learn that master weavers will not let anyone else prepare their materials, and that new learners practice on crooked roots or those that were scorched while being roasted or are just naturally discoloured. Practice happens with the roots that cannot be used to make a basket. Respect for the spruce trees, and the time invested in root harvesting, requires that no roots be wasted.

Conservation is a thread throughout this book. The harvester is taught to make decisions to protect the trees and avoid over harvesting an area. After the tree is thanked and the bark is harvested, it is prepared in the forest, so that the outer layer can be left there. This practice in itself limits what a harvester can take in a single day. There are a few instances where Delores recalls times where she has seen evidence that these principles were not followed. She gently reminds the reader that the Haida concept of Yah’guudang (respect) should ensure that nothing is wasted, and the harvester only takes what they need for personal use.

I have previously experienced great sadness when as a student I accompanied volunteers and staff from a university museum to harvest in a demonstration forest operated by the forestry program of that same university. The area where we harvested was slated for logging, so the staff began by telling the volunteers they could take as much bark from the trees as they could get. Thinking of their school programs, they took large quantities of bark, but they did not take the time to prepare it, deciding they could do that work later. Sometime later, when I entered one of the labs, I happened to find rolls of this cedar bark molding on a shelf because they did not remove the outer bark when they harvested or take the time to store it properly to dry. I took it outside to the forest but felt discouraged that the teachings the volunteers were being given were not complete – respect was missing. It is my hope that those who read this book will come to understand the importance of treating the forest and its gifts with respect. These lessons are there for those willing to learn them.

I particularly enjoyed the chapter about “The Haida Calendar” which discussed different types of basketry while also describing how Dolores’s family would move about Haida territory at different times of the year. Accounts of what foods they would gather, and how they were prepared and distributed, are accompanied by color photographs and watercolour paintings. Baskets for razor clams, seaweed, bird eggs and berries are differentiated. The longevity of the weaving tradition is also conveyed through a discussion about spruce root hats that also mentions one collected by Juan Perez in 1774 and the hat of the Long Ago Man, whose remains were found in a British Columbia glacier. This is also nicely illustrated with photographs.

This book demonstrates that traditional knowledge is about understanding how everything in the environment relates to each other, that it is a lens for understanding the world as it is today, not just as it was in the past. In the chapter “The Weaving Harvest,” Delores notes “Climate warming is changing harvest times and the time changes are likely to increase. The time may be coming when yellow cedar can no longer grow in Haida Gwaii and Southeast Alaska because it is too hot. Gauge the harvesting times by the warmth of the season. When the nettles begin to push their heads out of the earth it is most likely that the bark is ready.” In several places in this book, we see Delores give consideration to how things were done in the past, and how a respectful harvester should make choices today to ensure that the trees will continue to thrive after the harvest. In her discussion of cedar bark harvesting, for example, she cautions against harvesting too near to roads as the pollution could cause harm to the trees.

A thread throughout this book, and one that I have heard from other mentors in the Salish world, is that it takes time to properly learn how to master the skills of harvesting, preparing, and weaving materials. Delores explains that young people are meant to assist their mentors, and when they are older these gifts will be returned to them by younger community members.

Whereas the first half of the book takes the form of a life history, the second half of the book tutors the reader in a variety of forms of harvesting before advancing them to weaving instruction and basketry designs. The last two sections are well illustrated with photographs and diagrams that are beneficial to anyone who wishes to put theory into practice. Some of the photographs have labelled the wefts so that the learner can follow step by step. The amount of care and attention to detail put into crafting these lessons is considerable and makes this a must-have reference book for any student of basketry.

The book concludes with a chapter on weaving terms and Haida endings. In these pages, Delores reminds readers that this book is intended for Haida teachers and that other weavers may make items for personal use but should leave the sale of Indigenous weavings to Indigenous people. Essentially, it reminds readers that there is a difference between cultural appreciation versus cultural appropriation.

This book is recommended to those interested in traditional ecological knowledge, weaving and basketry, forestry, Haida culture, and Northwest Coast Art.

*

Originally from Victoria, Sharon Fortney holds a BA in archaeology from the University of Calgary (1996) and MA (2001) and PhD (2009) degrees in anthropology from UBC. She is the Senior Curator of Indigenous Collections, Engagement and Repatriation at the Museum of Vancouver, a job that includes liaising with First Nations communities for museum exhibits and programs and assisting with the care of Indigenous collections. She is also Chair of the museum’s Collections and Repatriation committees. Her interests include Salish basketry and weaving. [Editor’s note: Sharon Fortney previously reviewed a book by Carey Newman and Kirstie Hudson for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster