Founding father’s west coast perceptions

Paul Kane’s Travels in Indigenous North America: Writings and Art, Life and Times

by I.S. MacLaren

Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2024

$450 (cloth, boxed four-volume set) / 9780228017479

Reviewed by Christina Johnson-Dean

*

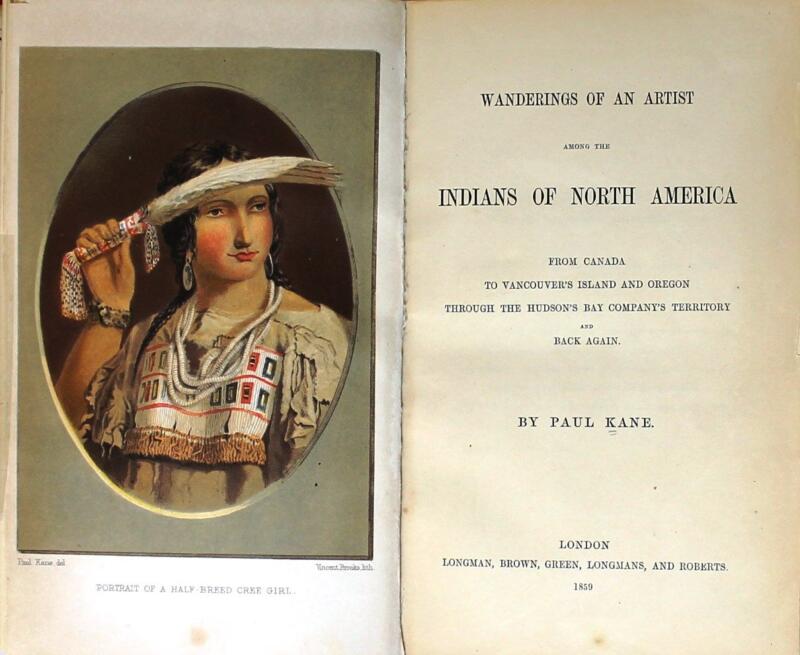

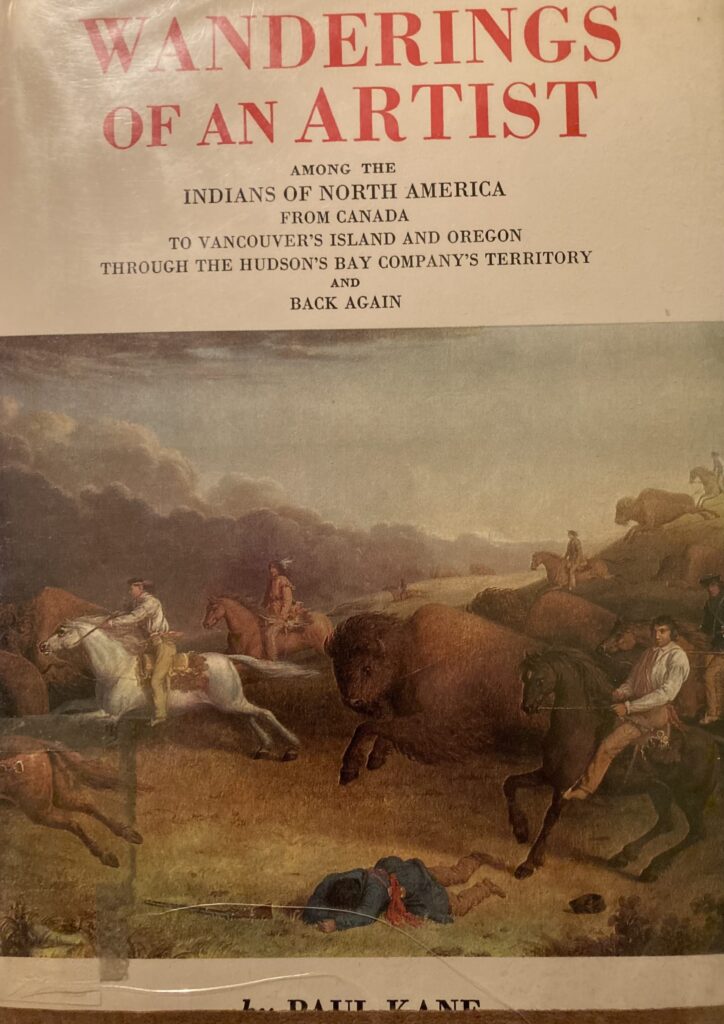

Cringe! It is indeed a brave writer who in this time of Truth and Reconciliation would tackle the work of colonial artist and traveller Paul Kane, whose journeys in 1845 and in 1846-1848 with the Hudson’s Bay Company from Toronto west to the Pacific Ocean are well documented, especially with his post trip studio paintings and the now notorious 1859 publication in his name: Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America. However, Ian S. MacLaren is no ordinary scribe nor amateur historian. As Professor Emeritus from the University of Alberta, he has in four lengthy volumes put together decades of research complete with critical thought and careful analysis of Kane’s Field Notes, Portrait Log, Landscape Log, extensive resources on Kane’s pre and post trip life, the two scribes for the handwritten manuscript for his book (not yet identified but not for lack of MacLaren’s deep search), as well as the publication itself.

There is more! Aside from the copious illustrations and comparisons of passages from Kane’s primary journals, the scribes account and the final publication, there are the 14 sections of the Preface, detailed maps, “Discussion” and “Notes” for each of the 25 chapters, which bring to life the “times”, which is academically thorough and comprehensive. If you are looking for an all-encompassing history of mid-1800s North America, its indigenous inhabitants and the multitude of visitors and immigrants, as well as what other numerous researchers and writers record about Kane, his artist contemporaries and travellers, this book is it. Hardly a stone was left unturned. And the point Is: as offensive as Kane’s studio and published work can be, a careful look at his original observations reveals that astute ethnographers, particularly those studying indigenous cultures, could very well find worthwhile material.

MacLaren is not the first to notice discrepancies. The original manuscripts and illustrations, are now mainly at the Stark Museum of Art in Orange, Texas, which were sold by Kane’s grandson Paul Kane III in 1957, when resources and interest in Canada could not compete with the American dollar and high interest in “the wild west.” These documents contrast with Kane’s studio oil paintings, many now in storage at the Royal Ontario Museum. In the ROM’s 2010 publication, Paul Kane, The Artist, From Wilderness to Studio by its Assistant Curator of Anthropology, Kenneth Lister, the author shows in a “coffee table” book Kane’s on-the trail sketches contrasted with the staged studio oils. As Kate Taylor writes in “Historian digs deep into Paul Kane’s problematic images of Indigenous People” in the August 10, 2024 Globe and Mail, MacLaren has noted that though Kane’s ethnography is haphazard, it may not be unreliable. “They can disown him and still take an interest.” For example, one of Kane’s logs was used as evidence in the Lekwungen Nation’s land claim on Vancouver Island in 2006. Also, a Cowichan knowledge keeper has respected Kane’s detailed descriptions of blanket-making and that his sketches of Northern Coast burial canoes are important records of lost artifacts. These are useful for recovery of artifacts from museums and other collections worldwide as well as land lost with legal “agreements” such as the Vancouver Island Treaties (sometimes referred to as the Douglas Treaties), started in 1850.

Born in Ireland and brought up in Canada after his family immigrated, Paul Kane was a self-taught artist, who worked as a sign and furniture painter in Cobourg, Ontario, before travelling around the eastern and southern USA as well as to Europe. He was able to arrange with George Simpson, Governor-in-Chief of Rupert’s Land, under charter to the Hudson’s Bay Company, to accompany the HBC’s trips in 1845 as far as the Great Lakes and then 1846-1848 crossing the land that is now the territory of Canada and the USA to the Pacific Ocean. Pertinent to British Columbia, Kane’s westward travel took him to the headwaters of the Columbia River and the Arrow Lakes in November, 1846 before following the Columbia to Fort Vancouver, now in present day Washington State.

After visiting various places in that area, Kane, the Chief Che-a-clack, four-five other native people, and the HBC’s Francois Xavier Cote and James Sangster paddled overnight in April, 1847 from Nisqually and the Puget Sound to Fort Victoria, which had become the new hub of operations for the HBC, which accurately sensed the looming dominance and takeover of the Columbia River area by the Americans. Kane was on Vancouver Island until July, when he returned to Fort Vancouver and headed east, arriving in Toronto in 1848. Though these times were before treaties, residential schools, and reserves, the lives of First Nations people had certainly been affected and disrupted already for several hundred years, and the European view of them as “noble savages” had changed to reflect the trauma they had suffered, usually called the five “V’s” – vicious, vain, violent, vengeful, and vanishing. MacLaren’s careful analysis of Kane’s original logs show differences from what the scribes wrote for the draft manuscript and certainly from the final publication.

However, Kane is still responsible for inaccuracies and pejorative ideas for allowing his name to be attached to Wanderings of an Artist: Among the Indians of North America as well as the dramatization and inaccuracies in his studio paintings, which he used to promote himself. He was a collector of items – clothing, headdresses, footwear, ceremonial items (rattles, staffs,) – and there are portraits of him dressed up in garments that he had acquired. In his studio work, he might portray a person with clothes or items from another tribe or group, contributing to inaccuracies and demonstrating a lack of understanding and respect. By today’s standards adults who dressed up “to play Indian” or created paintings of the bison hunt with guns in all its brutality because they would sell to people (usually of European culture in Kane’s time) who were fascinated by the “wild west” would be considered questionable if not repulsive morally and ethically.

To clarify, MacLaren discusses why such different perspectives made understanding so difficult. He notes how anthropologist Wayne Suttles found that the Coast Salish’s culture was markedly different from what Europeans had encountered elsewhere in the “New World” (especially East of the Rockies) in terms of agriculture, clan lineages, shelters, and linguistics (e.g. in what is now B.C. “chiefs” were leaders with prestige but without clearly defined political power, “tribes” were groups of people forming linguistic and cultural but not political units as we know them). He also includes writer Michael Marker, who described the Coast Salish as one of the most studied and elusively complex zones for anthropology and history, resulting in no comprehensive or unified way to view them. He wrote that “people organized themselves not in civic or political terms but as ‘aggregates of collective households’ such that land ownership in the traditional Coast Salish world was connected to family privileges and to traditions of resource management responding to a web of relationships that included plants and animals. Moreover, the concept of two economies was foreign to visitors and newcomers. ‘The subsistence economy was organized around the acquisition and circulation of food. The prestige or wealth economy, formalized by the potlatch complex, maintained the social order, affirmed rights and privileges for prominent individuals [for the purpose advancing their status, not their accumulation of worldly goods], and fortified relationships between villages in the region.’”

At the time of Kane’s visit, there had been no international border between Britain and the USA west of the Rockies (though it was in the process of being defined). The cultures around the straits were connected and shared many commonalities, just as they do today, though there are now different defining words, including Canada’s First Nations and First Peoples, as compared to “Native Americans” in the USA. Kane often used the term “Clallam” or “Klallam” to identify Coast Salish people and places (whereas now the term usually refers to those in the USA), though he also recorded Songhees and Esquimalt, the terms now used in the area for the people of indigenous ancestry. As for Esquimalt, he recorded that it meant “place to gather camas” while the meaning is now understood to be “place of gradually shoaling waters”. Esquimalt Harbour was to the west of Victoria Harbour and the land in between was known as Esquimalt,so Kane identified the Songhees village on the west side of Victoria Harbour mistakenly as Esquimalt Harbour. Today the area shares the names Victoria West (where the original Songhees Village was located) and further west is Esquimalt and its harbour.

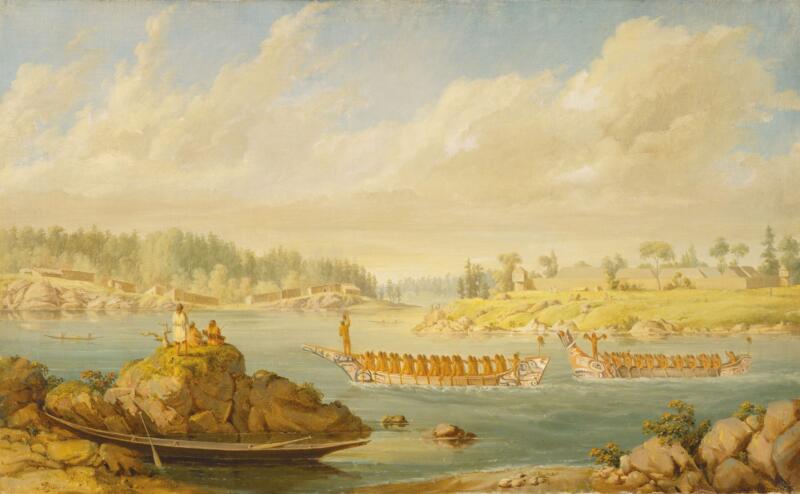

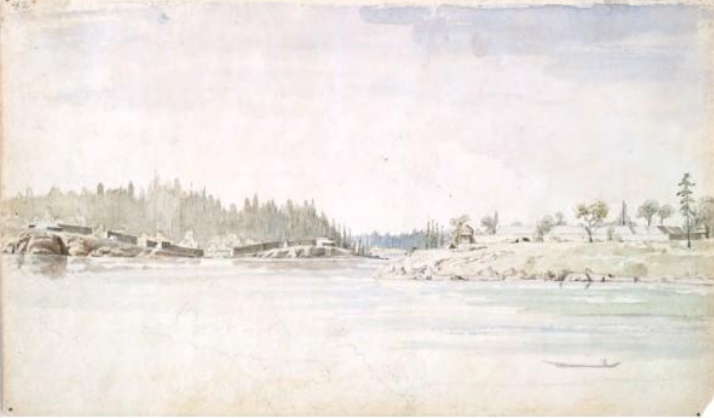

Though some places and people seem misidentified, many of his sketches are believed to have accuracies, which are worth noting, even if the studio oil paintings are composites from field sketches. Two works noted are The Return of the War Party and The Esquimalt [sic – should be Songhees village on Victoria Harbour] Indian Village. It is pointed out that they show Euro-Americans and Natives cohabited a place, each with distinct wooden structures, “with a clear (if not identical) sense of property and themselves as owners of it. Kane’s representations trigger one’s awareness that both settlements are established, not transitory, their inhabitants residents, not wanderers.” He sees the scene as celebratory for both communities viewing it and less of a colony of conquest and dispossession. In sketches that Kane exhibited at Toronto City Hall in November, 1848 after his return, one called “Indians returning from gathering Camas” seems to be a basis for the studio oil of the returning war party. It has also been conjectured that Kane did not actually see this event, but created it from stories. Was the subsequent oil painting (using European art style) oriented to an audience more interested in guns and war than in the benign activity of gathering edible bulbs? For that matter, why are there no sketches nor studio paintings of the stunning spring fields of grass and wildflowers, one of the very things that caused the HBC to recognize Victoria as an attractive and useful place to build a fort, and has entranced visitors to the area to this day? For all his attention to detail, the rich biology, particularly the edible and medicinal plants of the region seemed to evade him.

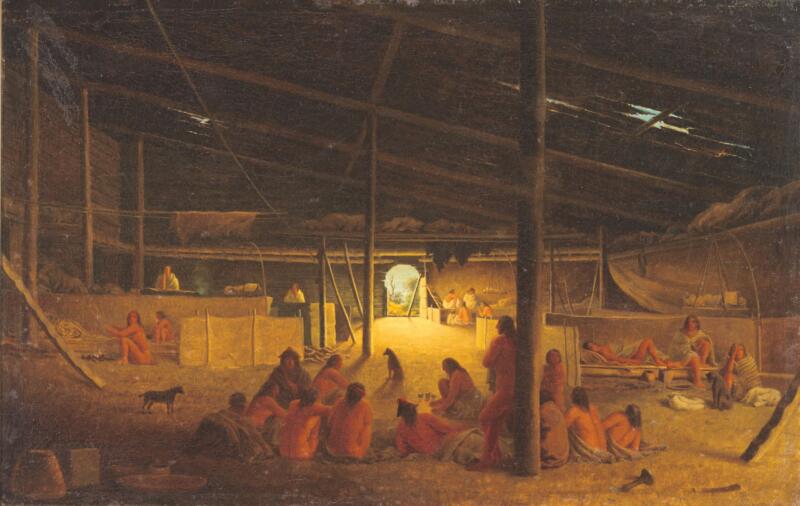

Of value to ethnology are the depictions of the buildings, people clad in traditional blankets, and various canoe styles (Munka styles with unique tall bow forms, Salish type, and Nuu-Chal-nulth or Chinook style with forward extending bow and vertical stern). Note that no researcher has found a Clallam village at Fort Victoria, and it is most likely a Songhees lodge with “Clallam” used generically for Coast Salish. In the sketch “Interior of a [likely Songhees] Lodge” the typical structure is depicted with pairs of posts and slanting beams between them with purlins supporting roofing boards, carved with lipped edges that overlap like long, wide interlocking tiles. Also seen is the arrangement of space – the raised sleeping platforms, storage areas and containers, cooking fire, dog, reed or cattail mats, people at work and rest. Other sketches show groups of people, one with a family group. More detail is depicted – food dish, storage box, wooden water pail, blankets, dogs, utensils. The studio oil Interior of a Lodge is a composite with the addition of the game of “lehallum”, of which there were many names and different materials. Kane’s sketch shows an outdoor setting with a group of people, though it is not clear if it is a mix of men and women. On the reverse of the watercolour sketch, which was exhibited at the Toronto City Hall, is an inscription “Indians gambling – the game of Lehallum”. Though there were many variations, the game in the Fort Victoria area usually was described as entailing a set of light and dark disks, which were shuffled and covered. The challenge was to identify the disk’s location.

The spinning of wool and the making of woven blankets were important activities shown in Kane’s sketches, including Flathead Woman Spinning Yarn and Interior of a Lodge with a Woman Weaving a Blanket Songhees Saanich. MacLaren provides various resources discussing the contents of the yarn, primarily dog hair (white, long wooly hair of a dog with bushy tail often shown in Kane’s work), but also the use of mountain goat hair obtained through trade and sometimes goose down and feathers. In the sketch of the woman spinning, she appears to be dressed in the traditional cedar bark garment whereas the studio painting has her wearing a blanket. She is using the Salish spindle and large wood whorl. The sketch in profile reveals her head shaped by forehead straps when she was an infant. In the studio painting a baby is seen in a cradle with the head strap, though Kane’s field sketches only showed this practice when in the Chinook and Columbia River areas. Kane’s work has also illustrated the typical geometric designs used by the weavers, seen in the composite painting and also in a studio portrait of a woman from nearby Whidbey Island. It is important to note that when Kane used Songhees or Saanich [WSANEC] to identify place, that specific designation has been useful in land claim cases, unlike the general Central Coast Salish term.

Other notable arts with a high degree of skill were basket weaving, shown in Kane’s sketch Clallam

[Songhees] Woman Basket Weaving, and of wood carving as in Carved Frontal House Posts and the

Medicine Masks of the Northwest Coast. The latter was the basis for a number of studio paintings, which have been questioned for their dramatic presentation and Kane’s imagination, rather than accuracy. The masks in his sketch were not typical of the peoples in the Fort Victoria area, and since Kane recorded that many people were reluctant to have him sketch them, it is unlikely that they would have posed in masks or other dress used in ceremonies, especially for healing or medicinal traditions. Kane was a collector and wrote that he was not always able to obtain items by trade or purchase. He felt that people would not allow him to sketch them or would not pose because of “superstitions”, and to modern sensibilities, his reluctance to respect such feelings or preferences are often seen as offensive. It is believed unlikely that Kane travelled further than the southeastern tip of Vancouver Island, but he did sketch items from other areas that were probably obtained by indigenous people who has traded or acquired them by other means.

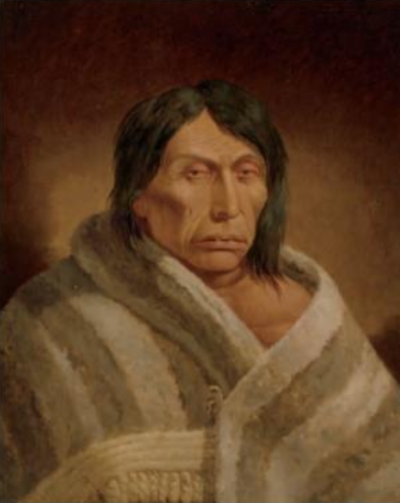

The contrast between the field sketches and a finished oil painting can be seen in the portraits of “Saw-Se-A, Head Chief of the Cowichan”. Note the importance of locale (Cowichan) of the sketch as compared to the general term Central Coast Salish for the studio painting. Other colonial traveller records offer information about Saw-Se-Sa, known for his trading at the HBC fort on the Fraser River and for potlaches. Kane did not note the term, but did write of these gatherings, which were hosted by a family or group of families who invited kin and dignitaries from communities with whom they had close connections. These events marked significant occasions, usually marriage but also birth, death, etc. Lasting several days to a few weeks, there was feasting, games, speeches, song and dance performances, but of most importance was the giveaway at a potlatch, when the host would distribute much accumulated wealth, gaining status in the process. The contrast between the portrait from the Portrait Log is noticeable, especially in the facial expression and the garment, much more valuable in the studio work. However, the difference between portrait in the field and the studio work is most marked in the images of Culchillum, Saw-Se-Sa’s son. In the scribed version and the final book, it is indicated that Culchillum did not allow Kane to take the hat to his tent to complete his sketch, but Kane’s field notes only indicate that he was not able to purchase it. Though the hat seems well documented in the sketch, the studio version shows the hat as if it had been “to the dry cleaners for cleaning and blocking”. The addition of necklace and the detail on the blanket “sheds light on how strongly artifacts in portraits define their subjects, turning individuals into clothes horses parading down or stationed on a fashion runway” and certainly more marketable in terms of art sales. These ceremonial pieces were undoubtedly of interest, and other sources indicate that human hair was used as well as eagle feathers which would twirl when a dance turned.

Though stories were repeated among travellers and visitors about the indigenous people, sometimes very erroneously, Kane’s field notes tell of witnessing the healing of a woman when making a sojourn north and east of Victoria, accompanied by Cle-A-Clach, Head Chief of the Songhees. The watercolour sketch of Mt. Baker from PKOLS (Mt. Douglas) shows the landscape and apparently they travelled to San Juan and Whidbey Islands as well as the south shores of the Juan de Fuca Straits. Though each group was distinctive, there were commonalities around the straits, and Kane’s sketches could be useful to verifying cultural aspects, such as the fire-making sticks, travelling lodges, canoe styles, fishing structures, and defensive building, (as seen at the battle scene at “I-Eh-Nus”, considered to be on the south shores of the straits).

Kane’s numerous drawings of canoes has prompted much discussion, since there were varying styles with some elaborately painted. Were they sketched from models, imagination, or on site? Of the Fort Victoria area, only Shovel-Nose and Munka Style Canoes, Songhees (Central Coast Salish) are specifically identified. Other depictions have the generic title Canoes, North Coast. The high bow is considered to be an advantage as protection when approaching enemies. Though some designs reflect traditions from groups much further north, Fort Victoria was visited by these people and items like canoes were acquired by natives and visitors alike. MacLaren comments on the quality and accuracy of Kane’s work in showing the complex structure and colour relationships of the painted design.

The sea and rivers provided important food sources, and Kane recorded in notes and sketches how fish, whales, other mammals as well as water fowl were captured. While in the Dungeness River area near a village called “Suck” (perhaps Sequim, but not to be confused with Sooke, B.C., which Kane did not visit, though there were apparently connections between the two communities), Kane drew Salmon Trap De Fuca [sic Juan de Fuca] as well as the chief’s daughter, Chaw-U-Wit, whose image shows the typical shredded cedar bark garment, edged trimmed blanket or robe, and ankle bracelets, possibly of mountain goat horn with “ingenious clasp, and engraved designs of circle, ovals, and the incised crescents and trigon shapes typical of the Coast Salish two-dimensional art style.”

The return trip from the southern shore to Fort Victoria was harrowing, with strong winds and

steep waves while the expertise of the native paddlers was impressive.

Kane returned to Nisqually and Fort Vancouver in June, 1847 and followed a route eastward,visiting many of the same places, before his return to Toronto in 1848. In November of that year, he was received well at an exhibition of his sketches at the Toronto City Hall, and in 1851 he succeeded in convincing the Parliament of Canada to commission 12 paintings. An 1852 exhibition of his paintings was received favourably, and George William Allan became an important patron, allowing Kane to make a living as a professional artist. He married Harriet Clench, daughter of his former employer in Cobourg and also known as a skilled painter and writer. Until his death in 1871, Kane enjoyed a successful career with highlights including his paintings being shown at the World’s Fair in Paris (1855) and in Buckingham Palace (1858). As times have changed, his theatrical paintings based on his travel sketches have been seen less favourably, but as I.S. MacLaren so carefully points out, there can be value in the details of his field notes and on-site sketches of landscapes, people, cultural customs and artifacts of his short time in the Fort Victoria area can demonstrate. The book is an intense and lengthy read, but certainly worthwhile.

*

Christina Johnson-Dean graduated from the University of California, Berkeley (B.A. in History with Art minor) and then trained as a teacher. After three years teaching in public schools, she took her retirement money and travelled around the world, teaching in Thailand and New Zealand, before settling in Victoria. She completed a M.A. in History in Art and served as a teaching assistant as well as creating local art history courses for Continuing Education. Since 1987, she has been teaching in the Greater Victoria School District. Her publications include The Crease Family: A Record of Settlement and Service in British Columbia (1981), “B.C. Women Artists 1885-1920” in British Columbia Women Artists (Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1985) and three titles for Mother Tongue Publishing’s Unheralded Artists of B.C. series: The Life and Art of Ina D.D. Uhthoff (2012), The Life and Art of Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher (2013), and The Life and Art of Mary Filer (2016). In addition, she contributed to Love of the Salish Sea Islands with an article about Gambier Island (2019). [Editor’s Note: Christina Johnson-Dean has recently contributed a retrospective essay of the life and art of Pnina Granirer, and reviewed the work of Sonja Ahlers, Gary Sim, Robert Amos, and Kathryn Bridge.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Founding father’s west coast perceptions”

So happy to see that Ian MacLaren’s epic scholarly journey with Paul Kane has reached a happy conclusion! Anyone who is interested in the amazing work that went into building this volume might want to read this. I am so looking forward to reading this book!