Memorializing ‘bums from the slums’

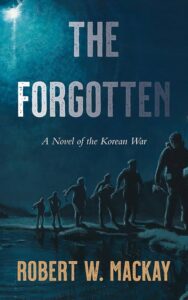

The Forgotten: A Novel of the Korean War

by Robert Mackay

Surrey: Now or Never Press, 2024

$26.95 / 9781989689752

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

A book with a single noun title could hardly make its focus clearer. In the case of The Forgotten, the subtitle is crucial: “A Novel of the Korean War.” Forgotten? A initial response by many a Canadian might well be curiosity, or, possibly, a little guilt. After all, this is the war that, even at the time, news media often called “The Forgotten War.”

The novel’s author, Surrey resident Robert Mackay, has not been the first to wish to ensure “remembrance” of the Korean War. The (literally) hundreds of thousands of annual visitors to Pacific Rim National Park’s Radar Hill will almost certainly have seen a commemorative brass plaque prominently placed at a sweeping ocean outlook. More than just praising the principles of “freedom” and “ultimate sacrifice” manifest in Canadian soldiers in the Korean war, however, this plaque delivers a comparatively detailed account of a particular battle and, even more particularly, praises the “2nd battalion Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry”—singled out, apparently, by the US for a unique military honour. Amongst other things, the memorial makes no bones about pointing out that the Canadians, fighting “hand to hand,” and employing a risky strategy, succeeded where both Americans and Australians had not.

Anyone who has read Mackay’s third novel and comes unexpectedly upon the plaque is likely to be startled to realize that described here is the very same battle the author positions at the novel’s climax. Neither plaque nor novel attempts to memorialize the war itself, though it involved over twenty countries as diverse as Colombia and Turkey and lasted three years.

Having decided, though, to bring at least part of the war to public awareness, Mackay (Terror on the Alert) clearly had to decide how the “forgotten” should be remembered. As a starting point, facts are key—and Mackay’s credentials for creating a knowledgeable memorial are substantial. With military experience behind him—as noted at the book’s end pages—he publishes a biweekly newsletter about Canada’s military.

As for the how of his memorial, Mackay, unlike those who made the plaque, does not deliver encomiums on heroism, courage, and glory—except, tangentially, at the end of the big battle. In novelistic terms, Mackay’s how likewise involves, first, storytelling techniques gauged to deepen the impact of the narrative and, second, details selected to bring to life a grinding and grisly combat.

Storytelling is fundamental: as in many other war novels (and films), the perspective is almost entirely that of a single protagonist. Like many war novels, this one documents the journey of a single soldier (Charlier Black) to the war zone, his training, his first encounters with armed conflict, his experiences away from the war zone, and, finally a mounting sequence of increasingly dangerous armed conflicts. In the process, not unexpectedly, the protagonist’s story involves rubbing up against a cast of memorable and variably sympathetic (or even abrasive) fellow soldiers and officers.

Since, however, Charlie must carry the entire burden of a memorial to the “forgotten war,” Mackay directs his protagonist carefully. Thus, he has his central figure occasionally (but only occasionally) register views of some large issues beyond his own immediate experience. At one point, for example, he first states, broadly, for the reader’s understanding, “The Patricias knew they were there to make sure Korea didn’t fall to Communism, and the North Koreans had attacked the South, setting off the whole war.” To make sure, however, that Charlie himself is the nexus of everything in the novel, and, possibly, to convey something of his own views, Mackay next writes, “Still, Charlie wondered if the UN had pushed it too far, chasing the North Koreans all the way to the Chinese border….” And if that isn’t enough, Charlie is stirred to become thoughtful about an underlying principle of war: “Maybe the Chinese soldiers didn’t have a choice about being at the war, any more than the American conscripts did.”

Mackay’s protagonist, however, unlike the Chinese and American soldiers, is not a conscript. As a Canadian, he volunteered. And that fact lies at the core of another major role that Mackay assigns to his protagonist. As much as this is a document of a slice of the war, it is a novel about a distinctive character and personality. Although Charlie Black, along with other figures documented at the end of the novel, was a very real soldier with a distinct military role, Mackay gives him an intense inner life.

And to highlight this inner life Mackay embeds it within a comparatively unremarkable external personality: in Charlie he has created a kind of decent Everyman—or, at least, Everysoldier. Very much a “regular guy,” he is competent, dutiful, determined, and (usually) controlled, his actions only occasionally driven by strong emotions. His last words are characteristic: when asked if he is feeling emotional, he says only two things, “Cripes no,” and “Let’s go.” The fact that Charlie has accidentally ended up in a platoon of “misfits,” the 13 Platoon, deepens the effect.

More central to Mackay’s construction of a memorial to the war, though, is what he does with Charlie’s thoughts and feelings. His motivation for going to the war is paramount: he is crushed by a sense of inadequacy because his older brother was killed in the Second World War, “a real war, fought by real men….” His driving force, then? “Charlie wanted to be a hero.” He wants to be a hero for his father, “the goal that had urged him on.”

It is not long before these motives turn to ashes: his father dies and the realities of war hit home. Although the author covers a lot of psychological ground with his representative soldier (including his regrets about his relationship with his girlfriend at home), Mackay emphasizes two traits. First, Charlie repeatedly feels “unworthy” and “inexperienced.” More often, and strikingly, he is terrified: “The sheer terror of lying in a hole in the ground while random forces beyond his control decided whether he would live or die constituted an unspeakable horror of its own.” Feeling at times “his hands shaking so hard he couldn’t settle on a target,” somehow he nevertheless carries on.

Mackay’s emphasis becomes double: smitten with doubts and terrors, his soldier nevertheless has moments when he feels “new motivation, a sense of belonging,” and even a “surge of pride.” Moreover, he uses Charlie’s interaction with others both to illuminate his protagonist’s qualities and to contrast them with those of his fellow soldiers.

At the one extreme there is the insufferably sabre-rattling and jingoistic Muller, incessantly given to outbursts like “We’ll stop those bastards in their tracks,” and “Watch out, you Chinks.…” At another extreme is Ridley, so terrified in the midst of battle that he skulks off to shoot himself. Charlie follows him, to find “his eyes … swollen and red, leaking tears that trickled through his stubbled red whiskers.” While dismissing Muller’s words as “braggadocio,” Charlie harnesses his jingoism: “‘Sure,’ Charlie tried to grin.” He adds, “If anyone can do it it’s us.” His reaction to Ridley is likewise steadying, talking the broken soldier round until he can function again. Charlie, whose most violent language is “cripes,” “for gosh sake,” “heck”, and “holy smoke,” functions as a soldier perfectly created to lie at the core of Mackay’s memorial.

Additionally, though, Mackay delivers to his readers a fully real memorial. This drive for “realism” takes on several different forms.

On the one hand, the military details are rife. Specialized terminology—“mags,” “clips,” “.303,” “Brenn,” “US Navy Corsair,” “DC3,” “Vickers medium machine gun,” “The section went to ground”—functions as a kind of a fabric for the whole world of war.

Add to this a sharp-as-a-razor sequence of combat details. Mackay goes to great lengths to make sure his readers experience as closely as possible what his soldiers experience, even down to the smells near a village of “woodsmoke and human excrement.” Most strikingly, his soldiers struggle through brutal Korean geography, a geography of rough hilltops to be fought over, exposed ledges to navigate, and rocky outcroppings behind which to crouch. The unforgiving ground in which the soldiers attempt to scrape trenches, like the relentless winter weather, at times seems to constitute an entire second enemy: “the only way forward was to follow along a ledge to the left of the razor-sharp ridge.” Indeed, in one of the most harrowing incidents Charlie is barely saved from a lethal fall over ice covered rock.

Occasionally, Mackay zooms out to a different kind of military detail: “The 16th Field Regiment, Royal New Zealand Artillery was part of the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade commanded by Brigadier Burke, as was 2PPCLI. At any given time the 16th Field could be given artillery assignments to protect the Patricias or others….” The relevance of this almost dizzying detail to subsequent action later becomes all too clear.

By far the most dominant military details, though, are immediate and sharp. Machine gun nests, exploding grenades, attacks, and counterattacks all form part of an increasingly intense sequence of battle scenes. Many of them are almost cinematic: “he and Ridley were back at the base of the ‘V’ where he could see the other trenches….”

Even more central to the impact of Mackay’s writing, though, is the way he makes his battles terrifying. Some of the terror transferred to the reader arises from the sheer numbers of enemy: “The enemy kept coming, absorbing the bullets, falling, others running between the bodies, closing fast.” The effect is amplified by full sensory assault: “The incomprehensible screams of the Chinese were close, bullets slamming into the back of the trench….”

Within this general mayhem, Mackay documents two particularly harrowing historical events. First: an incident of “friendly fire” when a US plane not only misdirects an attack on Australians, but, worse, uses napalm to produce a nightmare of “black twisted bodies.” Second: he makes viscerally terrifying the battle recorded on that plaque on Pacific Rim’s Radar Hill. As a desperate and risky measure, the New Zealand artillery, positioned behind the Canadian trenches, shoots endless rounds of explosives immediately in front of the Canadians, onto the advancing Chinese. Although the tactic ultimately works, the “blur of concussive blasts” Mackay recreates is overwhelmingly visceral.

At this point, though, the novel takes something of a turn. No longer primarily a documentation—while noticeably devoid of elevated words—the memorial becomes a commemoration: “The Patricias stood alone atop Hill 677, surviving so far on guts and determination….” A few pages later, Mackay repeats the point: “The ROKs suffered a defeat, and the Australians had withdrawn. But the Patricias held.” The closer focus on Charlie and his platoon a few pages later goes further: “There was a lot of swagger in the Patricias’ body language. Grizzled, tired, and grim, they came down off their hill.” Even Charlie rises to the occasion: “he was proud of the battalion, even more proud of the men of 13 Platoon.” Mackay’s memorial, it seems, is not to heroism but to grit.

In fact, to make his novel a full commemoration, Mackay breaks form in the last chapter of his book. No longer is a single, minor soldier the centre. The point of view becomes almost that of an historian, reporting some of the speech delivered by an American general: his words, like his sentiments, are dramatically elevated: “by their achievements…[they] have brought distinguished credit on themselves, their homelands, and all freedom-loving nations.”

Appropriate, in contrast, to the general mood of Mackay’s novel, is the fact that, in the penultimate chapter, there is not a trace of this final lofty tone. In asking to return to his own platoon of “misfits,” the “bums from the slums,” Charlie is told, they “never existed, not really…. They’re forgotten already.”

Forgotten? Like the brass plaque memorial on Radar Hill, Mackay’s novel is determined to ensure that the memory of (part of) this war and its combatants is not lost.

[Editor’s note: Robert Mackay will read from The Forgotten at Semiahmoo Black Bond Books in Surrey, Saturday November 23, 1-3pm.]

*

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at UVic and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, UVic, and finally Lester Pearson College in Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at Banff School of Fine Arts and UVic. He lives at Nanoose Bay. Visit his website here. [Editor’s note: Theo Dombrowski has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), and Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has reviewed books by Genni Gunn, Eric Jamieson, Adrian Markle, Tim Bowling, Lisa Brideau, Deborah Willis, Brady Marks and Mark Timmings, Darrel J. McLeod, and Max Wyman for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Memorializing ‘bums from the slums’”