Cross-countrying, amid grief

Moon Road

by Sarah Leipciger

Toronto: Viking, 2024

$26.00 / 9780735249691

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

*

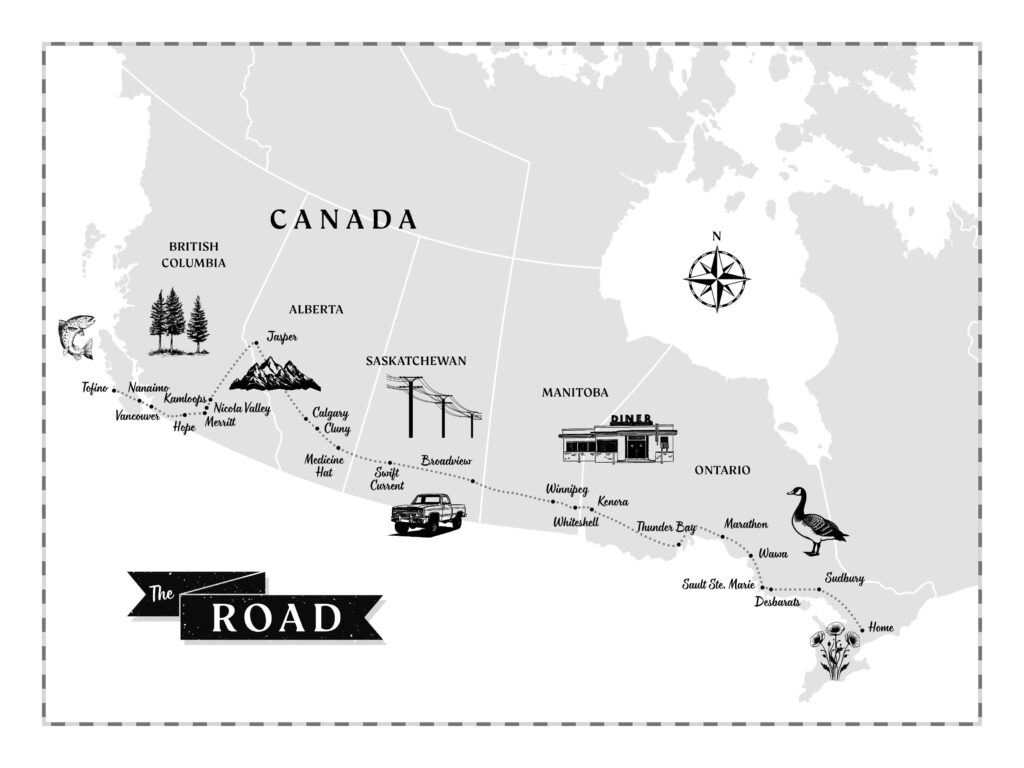

Moon Road by Sarah Leipciger is an evocative, confidently told story of Kathleen and Yannick, a former couple whose shared tragedy—the disappearance of their daughter, Una—culminates in a life-changing road trip from Ontario to the west coast of British Columbia. For a flashback-heavy road trip novel, there’s a real sense of immediacy due to the present tense Leipciger (Coming Up for Air) employs. The story is told in third-person limited, switching between Kathleen and Yannick, and alternating with chapters from Una’s point of view.

Not since Douglas Coupland’s The Gum Thief has an ostensibly clairvoyant, psychic-adjacent character been used in a way that feels genuine, rather than hokey. The opening paragraph of Moon Road is stellar:

Many years ago, Kathleen was told by a woman examining the mulchy tea leaves scattered in her empty cup that she would always be left by the people she loved. Kathleen didn’t believe in tea-leaf reading but she didn’t question the woman; neither did she ask her to elaborate. Kathleen knew what this tea-leaf reader meant, because she’s always known it herself: she is the one who stays behind.

After their divorce, Kathleen and Yannick continue to be friends, until an argument between them leads to nineteen years of silence without so much as a text. Although Kathleen, now a flower farmer—her attentiveness to rhizomes is wonderful—initially resists Yannick’s invitation to accompany him on a road trip to the west coast, she eventually changes her mind.

Kathleen’s hostility is, clearly, a carapace for her grief. Nevertheless, it does result in her treating Heather, a mother of four children who helps Kathleen with her farm—described by Kathleen as “a sweet girl but has no clue, like a dog”—with remarkable callousness. Though Kathleen has had lovers after Yannick, she hasn’t been in love since. The way she regards Heather’s marriage to Dave, whose “big ugly hands” are unduly emphasized, is that of cynical projection:

They’ve been together since high school, and as far as Kathleen can see, they aren’t exactly in love, because how can anyone be in love after living together as long as these two have? What’s easier to believe is that they were once in love and have come out the other side intact.

I was reminded of Charlize Theron’s character, Maeve, from Young Adult. Maeve is continuously horrible, even to people who are trying to help her—especially to people trying to help her. At one point, Kathleen says “you married people” with categorical contempt to Heather and Dave. Even so, Heather agrees to help Kathleen take care of the farm while Kathleen travels with Yannick, who is terrified of being on a plane.

Kathleen’s other friend, Julius, doesn’t receive the brunt that Heather does and is described thusly: “Julius may well be the only person in Kathleen’s life who doesn’t irritate her. … He’s full of fancy talk, and he giggles at the worst times, like when people are upset or dissatisfied, which didn’t go down well for him as the manager of the only drugstore in town.” Julius, like Kathleen, is an outsider. He’s from Toronto, which marks him as distastefully cosmopolitan in their small town in Ontario. Their friendship is a beacon of intergenerational platonic jubilance amidst the novel’s many fraught relationships and complicated histories.

The different ways Kathleen and Yannick behave as grieving parents are written about thoughtfully. Kathleen writes down the number of days since Una’s disappearance, every day. She hosts an elaborate awareness party annually to remind everyone about Una. She is haunted by an e-mail Una wrote that was never intended for her readership: “Una had never felt mothered.” Kathleen’s loss is seismic and undeniable.

Meanwhile, Yannick has had three subsequent marriages and other children, including another daughter, since their divorce. His grieving is less conspicuous, but his grief is every bit as real as Kathleen’s. Yannick’s insecurity over whether he is grieving adequately is exemplified here: “This was his daughter too, who was gone. Just because he didn’t staple posters to every mother-loving surface….” Grief is not a uniform monolith of specifically encoded actions and behaviours, but sometimes it’s treated as such. These empathetic portrayals of different ways to grieve are well-considered and feel true to the characters.

In characterizing Yannick’s late father, Leipciger excels in describing a character’s essence: “Every third word was ‘fuck’ or ‘plotte’ which apparently is very bad, and he ate raw onions as a side to his dinner. Not slices of raw onion, but whole. He would bite into an onion as if it were an apple…. You can have a face like old bark, nicked and scarred, and be kind.”

In Amitava Kumar’s Immigrant, Montana the narrator reflects on a former lover and describes her breasts as “milk white,” at which point I had a harder time taking the prose seriously. Kumar is not the first, nor is he the last author, to rely on milk to eroticize and glorify European paleness. Although Kumar’s novel has some very good writing indeed, unfortunately, what I remember best about this otherwise fine novel is my distaste for the aforementioned, downright cliché milk white breasts.Milk, for reasons Freud would probably love to explain, is often invoked when it comes to sensual descriptions, an ongoing tradition I would be more than happy to have become obsolete.

Germanely, Moon Road has a passage conveying the parental tendency to sentimentally adore every particle and iota, of a seemingly perfect infant; however, the writing is more awkward than deft: “Heather nods, eyes to the ground, absentmindedly kneading the baby’s milky thigh. Is there anything in the world harder to resist than a baby’s milky thigh?”

(One invocation of “milky” gave me pause; the subsequent repetition had me text my friends this very passage, asking: Is this normal? Is this how you feel about babies? Feedback, from a range of demographics, was mixed, ranging from “There’s something about (especially newborn) baby skin. It is so soft because it was just made, and it is the best thing in the world actually”; “Baby thighs are squishable but is milky for pale or for a milksplosion?”; “That’s weird and racist. Like baby thighs are cute if they are chubby but why say milky?”; “Please know this is not normal! I like babies!”; “It makes me uncomfortable, and I don’t know why”; and “Are they vampires planning on drinking this thigh?”)

Here’s a stronger passage, where former Victoria resident Leipciger writes poignantly about memory and time:

He was impressed, if that is the right word, by how rapidly a person can go from being alive to being dead to being a memory. Even before the elevator doors opened to take him and his father to the ground floor, his mother was a memory.

So when someone you love is missing without a trace, these distinctions get muddy. In the early days, Yannick didn’t know if Una was alive or dead, and now he can’t remember when he allowed the memory of the girl to replace the girl.”

The last two pages of the novel are spare yet poetic, entirely fitting. By the end, you’ll feel, if not peace, then perhaps, the desire to tell someone how much you love them—do it, now.

*

Originally from East Vancouver, Jessica Poon is a writer, former line cook, and pianist of dubious merit who recently returned to BC after completing a MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph. [Editor’s note: Jessica Poon has reviewed books by Katrina Kwan, Shelley Wood, Richard Kelly Kemick, Elisabeth Eaves, Rajinderpal S. Pal, Keziah Weir, Amber Cowie, Robyn Harding, Roz Nay, Anne Fleming, Miriam Lacroix, Taslim Burkowicz, Sam Wiebe, Amy Mattes, Louis Druehl, Sheung-King, Loghan Paylor, Lisa Moore (ed.), Sandra Kelly, Robyn Harding, Ian and Will Ferguson, Christine Lai, Logan Macnair, Jen Sookfong Lee, J.M. Miro (Steven Price), Bri Beaudoin, Tetsuro Shigematsu, Katie Welch, Megan Gail Coles, and Ayesha Chaudhry for BCR]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “Cross-countrying, amid grief”