Personnel de cuisine, romance tropes

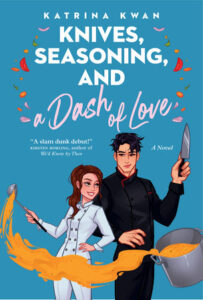

Knives, Seasoning, and a Dash of Love

by Katrina Kwan

Toronto: Random House Canada, 2024

$24.95 / 9781039012417

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

*

Knives, Seasoning, and a Dash of Love, Vancouver resident Katrina Kwan’s debut novel, has more than a tablespoon of vanilla sex orgasms and a dash of wish fulfillment. Though a restaurant novel, its real ambition is to make a reader horny, rather than hungry. Still, beyond carnal fulfillment, there’s a discernible, admirable attempt to subvert common interracial romance dynamics, while still adhering to recognizable romance tropes; however, the results are mixed.

The premise is charming enough—Eden Monroe is a short, freckled brunette with a bubbly, playful demeanour. This might shock you, but Eden is beautiful. Repeatedly, readers are told, Eden looks really great when she’s on her knees. After creative fabrication of her work experience, she’s hired as a sous chef at La Rouge, an upscale French restaurant in Seattle. Notably, she dropped out of the same prestigious cooking school as her new boss, Alexander Chen, who used to go by Shang.

Eden remembers Alexander—he’s never Alex—as being friendly and kind. As head chef, he’s Gordon Ramsay lite—all anger, Michelin stars, and intimidating masculinity. He also doesn’t seem to recognize Eden, who, apart from lying about her work experience, has other secrets.

From the onset, Eden and Alexander experience reciprocal sexual tension that threatens professionalism and mutual vulnerability. Clothes must come off, knives get sharpened, and secrets are shared. It’s not long before Eden does the restaurant equivalent of an Elle Woods, injecting cheerfulness where impatient tyranny used to reign. Instead of pink, though, Eden favours Japanese knives and positive reinforcement.

Eden makes Pad Thai Tacos and adores Asian fusion, whereas Alexander scoffs at Panda Express and clings to tenuous notions of authenticity. Alexander’s resistance toward innovation brings to mind Ali Wong’s film, Always Be My Maybe, which, while starring Keanu Reeves at his comical best, also seems to suggest that fusion is always contrived and inauthentic.

I did hope that at some point the novel would address how society has been collectively gaslit into genuflecting to the apparent superiority of French food, but it didn’t happen. I would eat Eden’s Pad Thai Tacos, though, any time. As far as initial personality clashes go, they’re on the side of mild because it’s obvious to anyone with eyes and ears that the two desperately wish to bone. Enemies to lover: check. Opposites attract: check. Two extremely pretty people: check.

In many ways, Alexander is a male lead you’d find in any Ali Hazelwood novel—good at his job, relying on standoffishness to disguise deep sensitivity and a generous wallet. Don’t forget the “massive,” eye-widening penis, admirable prioritization of female pleasure, and solicitous requests for consent. East Asian men have long been desexualized and given a hard time—pun absolutely intended—for purportedly having small penises, a scientifically inaccurate urban myth supported by the likes of the The Hangover, which is not the kind of movie anyone should be relying on for truths of the world. It’s no secret that while East Asian women and white men tend to be perceived as attractive on dating apps; East Asian men and black women fare the worst when it comes to optimized shallowness.

Though I admire Kwan’s likely intentions in depicting Alexander as tall, sexually desirable to white women, and yes, the aforementioned endowment—in other words, the opposite of a stereotypical Chinese man—this approach does have limitations. For one, it seems to be an inadvertent, tacit concession that Chinese men who are short, for instance, are less desirable.

There are attempts to evoke family drama. Alexander is estranged from his family, but the alacrity with which he is welcomed back brought to mind The Brady Bunch; the only real difference was, there were more dumplings. If there are Chinese families that forgive this quickly, I’ve never met them. Meanwhile, Eden’s uniquely traumatic family drama, while indisputably sad, never feels as weighty as it should.

Alexander’s family can’t get over how beautiful Eden is and, per the entirety of the novel, not a single person remarks on her whiteness, which struck me as both disingenuous and unrealistic.

In a novel that repeatedly had microaggressions addressed to Alexander from villainous white people, there was a strange reticence when it came to discussing the actuality of their interracial romance. Given the frequency with which East Asian women and white men are romantically involved, it’s worth pointing out that the reverse is nowhere near as common. On Reddit, the subject of East Asian women and white men pairings make for some truly frightening Reddit threads bitterly castigating the interracial phenomenon with vitriol reeking of self-loathing, internalized racism, and misogyny.

There are a couple of moments where Eden is more indignant—at least vocally—than Alexander when his “true” ethnic origins are asked about. Eden’s indignation and Alexander’s more muted responses had credibility—the white woman not being actively discriminated against has all the morally correct pathos, and the Asian man being unfairly targeted just wants the conversation to stop. Why should this be the case? The dynamics are not explored to their fullest potential, but certainly, the set-ups have promise.

While I don’t expect a romance novel to have sophisticated commentary on interracial phenomena, I was disappointed by how tepidly abortive the attempts to address racism and anomalous interracial dynamics were. To have zero commentary struck me as implausible, about as believable as shower sex going smoothly—which also happens in this novel. Spoilers: nobody slips a disc! No difficulties are had whatsoever between the couple’s major height discrepancies in a perilously slippery setting. And please, do not try this at home.

As befitting a book where the couple work in a restaurant, there’s a lot of food. Eden makes a saffron risotto with licorice extract, which Alexander initially mocks—you’d think someone who actually completed culinary school would be less skeptical of seemingly disparate ingredients, but maybe this is just an indication that school narrows minds, rather than expanding them.

In turn, Alexander makes Eden a simple pasta with red chili flakes, lemon, garlic, and parsley—this is my go-to I-don’t-want-to-buy-ingredients dish and it’s a good dish. It’s also not remotely challenging to make. Eden, a naturally talented chef, is blown away by how Alexander can handle “twenty different steps” at the same time, at which point I began to doubt the accuracy of the ostensible expertise of cooking these characters had. Eden’s awe over Alexander’s ability to make a Very Simple Delicious pasta dish with the reverence of watching someone make Peking duck while holding a baby and conducting a Beethoven symphony is like saying Alison Roman revolutionized the chickpea.

At this point, I texted a friend, who wisely said, “I think people are reading for sex, not cooking accuracy.” Remember: this is a romance. The restaurant is just a vehicle for the romance.

But enough of that. Let’s get to the sex: I appreciated that using condoms and getting tested for STIs before having sex are both given prominence. There’s no raw dogging, or dubious promises of pulling out, or worse yet, negating the very real risks of pregnancy and venereal diseases for the sake of fantasy. Protected sex can be enthusiastic sex. Yay!

Eventually, though, and this probably tells you what a reprehensible person I am, I started craving unsafe sex, if only so I could be rewarded with a scene of a couple rushing to the pharmacy to responsibly buy Plan B. What, buying Plan B together isn’t romantic? I guess though, that wouldn’t be as romantic as secretly being on birth control and later opting for raw dogging.

The first time Eden and Alexander have sex—if you’re into delaying pleasure, you’ll have to wait more than 178 pages for getting some—they are immediately in sync; everybody orgasms; Eden has more orgasms than Alexander and even has two during penetrative intercourse, the latter of which stretches credulity. Freud would be so proud of Eden’s “mature” orgasms. It’s all part of the unrealistically good sex playbook. I told another friend about the rather improbable level of ecstasy Eden was experiencing and his response was, “This is just as unrealistic as Pornhub.” I suppose, though, that is the point.

Everybody’s clothes come off without any awkward fumbles; Eden’s white thong matches her white bralette; Alexander’s “big” member silences anyone who still assumes, incorrectly, that Asian penises are microscopic. Eden repeatedly experiences effortless orgasms from penetrative intercourse; even Alexander is surprised. Commonplace, realistic heterosexual sex doesn’t usually make for joyful escapism, so in this sense, perhaps the novel is delivering amply on its precise intentions. A documentary, nor a realistic portrait, this is not. Remember, the genre is romance.

Before Eden, Alexander has a friends with benefits situation with Bea, though it’s admittedly very low on friendship. Alexander finds Bea to be annoyingly loud during sex and their sex is always rough, the way Bea prefers. I was curious as to whether Bea, like Eden, was also white, in an attempt to ascertain whether Alexander had a certain preference, but Bea’s ethnic background is never explicitly stated. Alexander finds that he doesn’t mind how much noise Eden makes—there’s something about her that demands respect and compassion and seems utterly angelic. It’s almost as though Eden is on a pedestal she’s in no danger of leaving. I was happy to see, though, that Bea was never written as a clingy character redolent of jealousy.

That being said, however genuinely supportive Bea is of Alexander wanting to romance Eden, I felt uneasy with Alexander’s seeming dismissal of Bea as a person. It was not, in fact, entirely clear whether Alexander thought of Bea as a person. I’m all for consensual sex without the relationship escalator, but it did seem as though Bea was just a set of orifices until someone less confident, more angelically damsel in distress came along. More Eden, in other words. As for Eden’s previous dalliances in romance, we are given no information and this, I think, is a lost opportunity to create more depth.

The food and restaurant details ranged from seriously mid, to moderately drool-worthy; for the most part, food was more a prop than anything of credible sustenance. The food critic seemed more a villainous caricature ODing on modifications than a real critic, who would probably rather dine in anonymity for a more honest appraisal. I experienced mild consternation over the continued use of the word waiter, which, for better or worse, has long been supplanted by server. The romance is, I think, sometimes paternalistic, sometimes genuinely lovely, and often unrealistic—which is exactly what the genre is for. Because of this novel, I’m waiting for some gorgeous man to buy me Japanese knives, which, if anyone’s listening, is way more useful than diamonds. I’m not holding my breath, though.

There’s potential in the subversive interracial premise, but the dynamic goes under-explored. When it comes to sex, there could have been more—after all, that’s why we’re here, right? The kink factor is basically nonexistent, unless eating ice cream off a very attractive, muscular man, counts as adventurous. It’s all tame and mutually pleasurable, with no need for a safe word. None of this is remotely objectionable; I don’t mean to vanilla-shame. Quite the opposite, really. But definitely, there could have been more seasoning, by which I mean, of course, abundant sex.

The number of consecutive bow-tied resolutions in the end was staggering. I felt as though I had overdosed on Splenda. But then, in a world where choking without consent is de rigueur, where any likelihood of the Paris Agreement making a difference is a big lol, and the overall state of American democracy is frighteningly volatile, an excess amount of artificial sugar, I think, is the least of our problems; it may well be a welcome respite of unreality. I’d rather read this book than have a husband. Remember, this is a romance.

*

Originally from East Vancouver, Jessica Poon is a writer, former line cook, and pianist of dubious merit who recently returned to BC after completing a MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph. [Editor’s note: Jessica Poon has reviewed books by Shelley Wood, Richard Kelly Kemick, Elisabeth Eaves, Rajinderpal S. Pal, Keziah Weir, Amber Cowie, Robyn Harding, Roz Nay, Anne Fleming, Miriam Lacroix, Taslim Burkowicz, Sam Wiebe, Amy Mattes, Louis Druehl, Sheung-King, Loghan Paylor, Lisa Moore (ed.), Sandra Kelly, Robyn Harding, Ian and Will Ferguson, Christine Lai, Logan Macnair, Jen Sookfong Lee, J.M. Miro (Steven Price), Bri Beaudoin, Tetsuro Shigematsu, Katie Welch, Megan Gail Coles, and Ayesha Chaudhry for BCR]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Personnel de cuisine, romance tropes”