Finding community through quilting

Knots and Stitches: Community Quilts Across the Harbour

by Kristin Miller

Qualicum Beach: Caitlin Press, 2023

$26 / 9781773861203

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

A small quilt by Kristin Miller hangs on my wall. It’s called “Windy Day” and there is a lot going on. There is also a lot going on in the cover picture of this book, but the scene does not seem to be particularly windy. A bunch of women, ten or so, sit on the grass intent on several quilts, one standing and peering closely at the work.

A lot goes on inside the book too: a memoir, a meditation on community and friendship, friendships which continue longer than love, an evocation of landscape, hope for the future.

The memoir does not begin at the beginning. By the time we meet Kristin Miller at the end of the 1970s, she was already an accomplished fabric artist with a career as occupational therapist. She and her partner were landed immigrants from Seattle living in Vancouver. She tells us: “I came north for a short visit in 1977, left, came back, and stayed for twenty-two years.” Across the harbour from Prince Rupert, 1000 kilometres north of Vancouver, they find the tiny settlements of Dodge Cove, Crippen Cove, and Salt Lakes, with gathering places such as Function Junction, “a dilapidated tugboat base taken over by sea-struck hippies” – and an “oddball bunch of folks” who soon made her feel at home.

She dealt with personal tragedies: the loss of a baby and hope of future babies, and the subsequent crumbling of her marriage: “My body slowly healed, but my heart did not… Angry at the world, at myself, at doctors, I cut myself adrift by drastically changing my lifestyle and giving up on my profession, my marriage, my conventional ideas of stability.”

It was the right decision. Instead of depression and self-pity, “I now had real, elemental dangers to focus on: storm, fire, getting lost in the fog.” She was buoyed by her neighbours’ “casual acceptance” and “nonchalant and unquestioning support.” In the Salt Lakes area, she made three particular friends Linda, Lorrie, Margo. Soon she and the reader become as involved in their stories as in her own, and her telling invokes a feel of place and community: “The smell of woodsmoke and creosote mingled with the acrid singe of wool socks hanging too close to the fire.”

Despite their choice of lifestyle, these people were not drop-outs. Most had jobs – fisher, post office clerk, net mender, even social worker. Miller depicts them in vivid vignettes: “Linda on her net-float when it was raining or blowing. Without her friends, without her jaunty hat, she would stand hunched and enduring in the wind and water sluiced down the hood of her grey raincoat, her needle never ceasing in its loop, catch, tighten.” One feels the elements, the rain and wind, emotionally and physically. The “wild parties” seem like part of nature. Couples came and went, “seemingly without guilt or jealousy or remorse.” Courtship rituals were “eccentric.”

Miller describes herself as “exceedingly cautious.” She was “an anxious but determined boater” and a willing but shy participant in the community. She, like her neighbours, was making up her life as she went along. In her house too “everything was makeshift” but everything served its purpose or was adapted to do so. There were times when her singleness was too much like the weather, forlorn as “the rain fell and my mood matched the weather. Bleak, cold, lonely.”

As Miller tells how she shared her skills and imaginative approach, she does not insist on being the heroine of her own memoir. Observing the “strong women of Crippen Cove,” she contrasts the trees they have chopped with the quilts they are embroidering and recognises that the physical is only one kind of strength: “Sitting in the late afternoon sun drinking tea with my Crippen Cove friends, I watched calloused fingers grasping needles, rough hands smoothing soft fabric, strong arms tugging gently coloured threads. These robust, vigorous women might not fit the stereotype of the dainty, ladylike quilter, but their quilts embodied warmth, love, and caring in a practical as well as symbolic way.” The designs and solutions she describes more often appear to come from the other quilters than from herself. Although the reader may suspect she is the force that binds them, and yet when they move away, they take their quilting talents with them.

Of course, it could not last. It was not a way of life for growing families and middle-aged bodies. As people moved away from the wilderness islands, and her community changed, Miller felt the old pangs of childlessness, considered adoption, and tried fostering. She was lonely: “I held on like a limpet or a sea slug to a barren rocky shore… The only people left were a few grizzled, disillusioned, hard-drinking guys and me.”

Of course, that could not last either. By now the reader is pretty sure Miller is not going to fade away in fits of moping, and she did not: “At a writers’ group I met Iain.” Anyone who has met Iain, as I have, would recognise him immediately from her word-picture. Her descriptions of people and places have felt true all along, and here is proof positive of that truth.

He was editor of the local newspaper and working towards becoming a creative writer and the winner of numerous prizes, including the Governor General’s Award. They went for summer-long voyages on his sailboat. For eleven years they were keepers of the CBC Hill tower transmitter building at Dodge Cove still in the Prince Rupert area. The helicopter pad became “a spacious outdoor workspace” ideal for collective quilting.

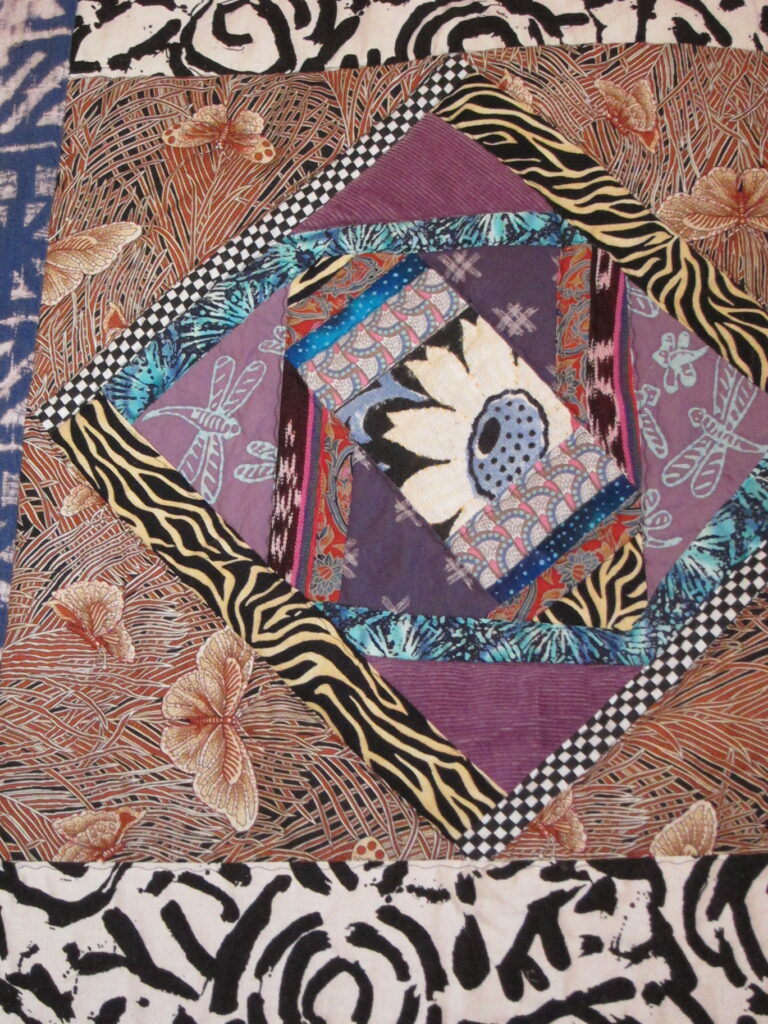

Once again, she was the centre of a group. They create “The Quilting Amoebae” – “a colourful, amorphous entity that absorbed anyone who wanted to stitch on a quilt.” When they were invited to exhibit their work in the old Museum of Northern BC in Prince Rupert they named themselves the “Coastal Quilters.” It turns out that Miller had all along been documenting and photographing the collective work in which she was involved. Now she was invited to write a research paper for the American Quilt Study Group, to travel to Maine for a seminar and to exhibit the Coastal Quilters’ work.

In 1998, the transmitter was automated, and she and Iain moved many miles south to Gabriola Island. She left the “sisters of her heart,” but there were trips to Vancouver where she could go from house to house to visit the same friends as at Crippen Cove. They gathered for celebrations, parties, reunions; there were signs of age, but she remarks “we were young for so very long.” On Gabriola they both flourished in their chosen art forms.

Miller contrarily calls her final chapter “It’s not the end of the story.” When she and Iain separated in 2017, she moved to Powell River, formed new attachments, and kept on quilting. She tells what she is doing, because by now she has made us want to know, but as always she is not the whole focus of the narrative. The colour portfolio which concludes the book showcases the work of 15 quilters who continue to initiate new ways of collaborating and new ways of design.

I appreciate the “List of Coastal Quilters 1979- 2022” and the index of quilts. But one does not need to be a quilter or even care much about fabric arts in order to welcome Miller’s book for its glimpse into a time and a way of life which changed our society and offered a new sort of freedom which we have not yet lost.

There is a slideshow of the quilts on Miller’s website .

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve was born in Fiji, grew up in Quebec, and has lived most of her life in British Columbia. Her most recent publication, in Dorchester Review #25 (Spring/ Summer 2023) revisits the history of pre-colonial Fiji in the writings of her paternal grandmother Richenda Parham. [Editor’s note: Phyllis Reeve has recently reviewed books by Julie Wheelwright, Rika Ruebsaat, Doug Harrison, Dave and Rosemary Neads, Robert G. Allan, Mother Tongue Publishing for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Finding community through quilting”

Thank you, Phyllis, for a great review of my book. I’m honoured!