MacDonald’s vision

To See What He Saw: J.E.H. MacDonald and the O’Hara Years: 1924-1932

by Stanley Munn and Patricia Cucman

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, with the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, 2024

$65.00 / 9781773272504

Reviewed by Ron Dart

*

I have spent many a week over the decades at Abbot, Stanley Mitchell, and Elizabeth Park Huts in Yoho National Park, but some of my fondest memories are rambling the trails and climbing the peaks in the Lake O’Hara area. So, it is with some delight, I was asked to review J.E.H. MacDonald’s 1924-1932 short trips to O’Hara and the significant paintings he did there.

To See What He Saw is the work of many a decade and a packed tome of MacDonald’s paintings in O’Hara but the text, in this solid and sound book, reveals much about the history of O’Hara, MacDonald’s vision of depicting the weather seasons, mountains, lakes, cabins, and trees (occasionally people) but also the friendships developed when in O’Hara. I have enjoyed reading and rereading over the years Lillian Gest’s (in its original and updated form) History of Lake O’Hara, Jon Whyte’s Tommy and Lawrence: The Ways and the Trails of Lake O’Hara (in which MacDonald’s visits to the Lake O‘Hara area are amply recounted and recorded) and Lisa Christensen’s The Lake O’Hara Art of J.E.H. MacDonald and Hiker’s Guide but To See What he Saw ups the quality to a much higher and more informative level.

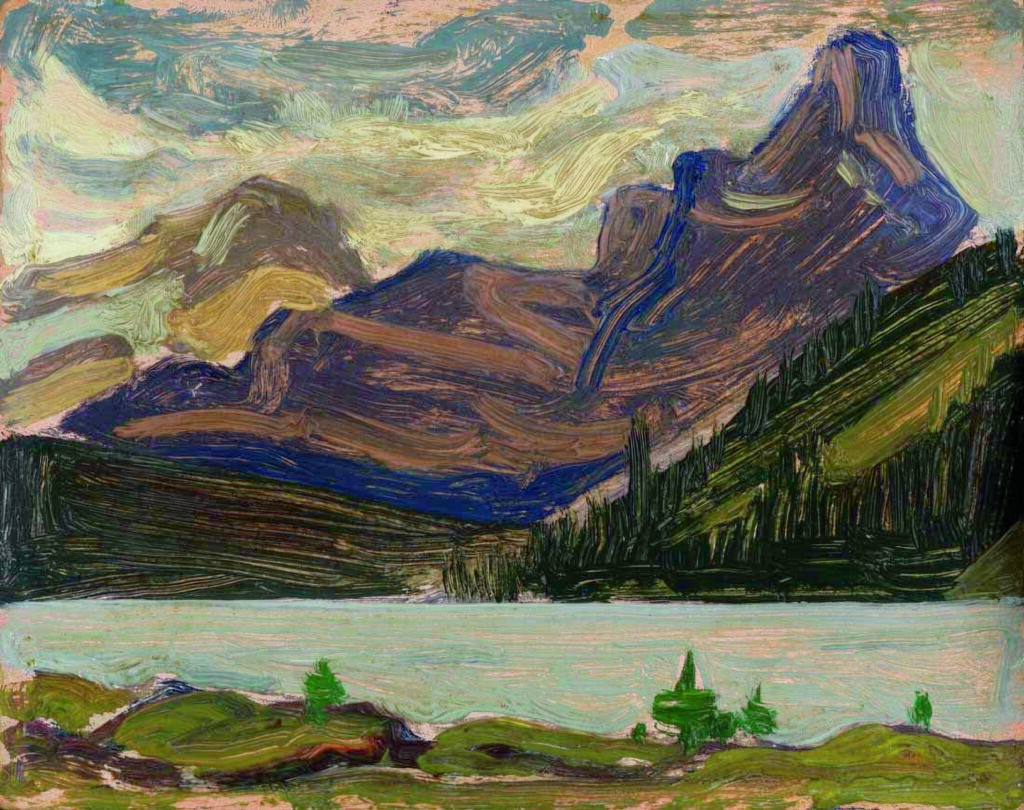

The bulk of the beauty of this comprehensive approach to MacDonald’s sketches and paintings in O’Hara is covered in seven areas in which MacDonald did most of his observations and sketches that led, in time, to many of his paintings: 1) Shores of Lake O’Hara, 2) Wiwaxy Slopes to Oesa, 3) Opabin Pass, 4) Alpine Meadow, 5) Odaray Bench and McArthur Pass, 6) McArthur Meadows, and 7) Kicking Horse Valley and others. Each of the paintings highlighted in these sections, interestingly enough, has a modern photograph that brings the older visual painting into relief, photograph zeroing in on the site of the painting. The text written in each of the seven sections clarifies the days, weather conditions and context of the paintings and who MacDonald was mostly with, usually Peter and Catherine Whyte, (now legends in the area with a Banff Museum named after them) and George and Adeline Link. MacDonald was in the O’Hara area, in his many trips, in late August/early September, a splendid time when golden larches are at their best, snow often returned to the high alpine and many days an inviting charm. Needless to say, other days not so pleasant, low-lying clouds and plenty of rain. MacDonald had a unique and uncanny way of articulating the moods and sense of the season. But, pages 19 to 196 in To See What He Saw brings together the finest overview yet published, in intricate detail, of the painting vocation of MacDonald in O’Hara.

Chapter Three in To See What He Saw moves from a laser like focus on the paintings to “The Trips.” This much shorter section is yet again a superb and in depth summary of MacDonald’s time spent in each of his trips to O’Hara, replete with photographs, a calendar of his daily activities when there and journal entries—well worth the sitting, with, as a companion to Chapter Two, “MacDonald’s O’Hara Legacy”. This section ends with 1931-1932 when MacDonald’s trips had ended but when he continued to paint and more meditative reflections “after the trips.”

Chapter Four settles into “The Studio Works,” a distinctively short chapter but with plenty of MacDonald’s painting displayed and front staged (also a lovely photograph of MacDonald as an entrée to the section).

Chapter Five turns to more of MacDonald’s literary endeavours with “Transcriptions,” the much-needed hiking companion to the sketches, photographs, and paintings. I was reminded of Emily Carr in this section—many books on her tend to lean towards her paintings whereas her literary life was generously alert and alive—much the same with MacDonald. This section lightly lands on a variety of publications by MacDonald, including “A Glimpse of the West” (1924), “My High Horse: A Mountain Memory” (1929), and his O’Hara diaries from 1925-1926, 1928 (Part 2), 1929, and 1930—some splendid sketches embroider the evocative and more personal text. To See What He Saw is brought to a fit and fine close with a generous sampling of MacDonald’s O’Hara paintings in a compact visual way.

There can be no doubt To See What He Saw has set new standards for how to see O’Hara, MacDonald scholarship, complex nature of the Group of Seven and Banff ethos of Peter and Catherine Whyte, the Links, mountaineering culture (including some Swiss Guides that interested MacDonald), and Lawrence Grassi. There was some mention in To See What He Saw of Georgia Engelhard (who was a fine painter herself and niece of Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keefe). There was a period of time when MacDonald was in the O’Hara area in the same years as Engelhard, although Engelhard was a mountaineer in a way MacDonald certainly was not. But, a conversation between the two of them about painting would have been most interesting to sit in on.

I mentioned at the beginning of this review that I have spent many a pleasant week in the O’Hara area and To See How He Saw by Stanley Munn and Patricia Cucman has given me new eyes to see the area in a more nuanced, reflective and memorable manner. This is an A++ keeper of a weighty and informed tome—a must own and read from many perspectives—indeed, a 10-bell beauty.

montani semper liberi

*

Ron Dart has taught in the Department of Political Science, Philosophy, and Religious Studies at the University of the Fraser Valley since 1990. He was on staff with Amnesty International in the 1980s. He has published 40 books including Erasmus: Wild Bird (Create Space, 2017) and The North American High Tory Tradition (American Anglican Press, 2016). [Editor’s note: Ron Dart has recently reviewed books by Arnold Shives, Torbjørn Ekelund, Jan Zwicky, Jan Zwicky & Robert V. Moody, D.L. (Donna) Stephen, and Elizabeth May for The British Columbia Review. He has also contributed a reflection on several aspects of mountaineering life in his Missives from the Peaks as well as four essays: Canadian mountain culture and mountaineering, From Jalna to Timber Baron: Reflections on the life of H.R. MacMillan, Roderick Haig-Brown & Al Purdy, and Save Swiss Edelweiss Village to The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “MacDonald’s vision”