Grim ends, fresh starts

A Blueprint for Survival

by Kim Trainor

Hamilton: Guernica Editions, 2024

$21.95 / 9781771838627

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

*

Things change and stay the same. Percy Bysshe Shelley, the romantic poet, wrote Prometheus Unbound about the Greek hero who defied the gods to give humans fire.

In one of his modern live-action reenactments, Elon Musk wants to go to Mars because Earth might get broken by a rock. He does this using rockets—fire.

In another remake, Kim Trainor wants to go to Earth because Earth is burning. To do so, she sets aside ideas of heroism and humanism.

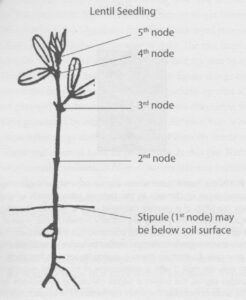

A Blueprint for Survival is a grave, a furrow, in which Trainor, in “Codex,” sets seeds, such as lentils:

Her mashup of a number of possible textual modes is appealing. Her ability to fully inhabit them less so. To Heidegger, the environmental philosopher who argued for local attachment as the root of language and culture, Trainor adds a humanism refreshingly driven through a kind of Talmudic annotation. Identity here is communal. The surface of the poems is a drafting table, a place for thinking out loud with marks placed on paper—

Such intense ability to read romantic human identities in layers takes us to another one of this book’s ancestors: Shelley’s wife Mary. In a little evening’s entertainment to tease Shelley and the poet Lord Byron in the rain above Lake Geneva in 1816, Mary wrote a ghost story called Frankenstein. No text in English has escaped its orbit yet, not even Trainor’s, whose acute observational distance and reframing of human identity is solidly in Mary Shelley’s tradition.

There is nothing local about this book. Human intimacy remains interpersonal, often touchingly so, often observed through a veil. The Earth remains large and threatening. A blueprint for survival is a map of one writer’s attempt to create a bridge by reading the world as text. In intellectual terms, it is a tour-de-force of contemporary intellectual mythology. In British Columbian terms, it is an example of the kind of vision that so often leaves Vancouver for the hinterlands, which it then defines in the textual and social patterns of Vancouver’s own individual mythology, whether it is in the provision of powerful intellectual tools or a bunch of hunters with $200,000 worth of gear making an expedition to shoot a moose. All are attracted to the land beyond Hope.

In the long Western tradition of poetry, this land of Nature, whether through Mary Shelley’s or Trainor’s textual lenses, stands solidly in the genres we know as “the ghost story,” “horror movies,” and apocalyptic climate news. It also stands in the tradition of Rumpelstiltskin, the cultural figure older than Gilgamesh who conferred the power of survival by teaching a young woman how to navigate paradox and riddle.

All explore the limits of freedom in the gap between social and environmental expectations and personal feelings of identity and separation. “A blueprint for survival” brings the tradition forward by replacing romantic notions of art and culture with rational ones: not the girl who must spin gold from straw or die but the little dancing creature that gives her one future (immediate survival and social power) by doing so, yet threatens to take another (her firstborn child; her future) unless she embodies its paradox—

Trainor does no better at the riddle than Mary Shelley did. Shelley’s text was based on the story of a certain Konrad Dipple, who dabbled in conspiracy theories and dissected corpses in a mix of science, alchemy and madness at Castle Frankenstein, just outside the German city of Darmstadt. (The site is now used for Goth weddings.) Staying overnight on their way south from England to Switzerland, Mary and Percy Shelley were entertained with Dipple’s story.

In the version Mary wrote a few days later, she proposed that a certain Dr. Frankenstein created life from sewing together bits of corpses and zapping them with electricity from a lightning strike. Eventually, the “monster” was not accepted as human. To survive as an independent, thinking, ethical being, it struck out to experience the planet on its own.

A Blueprint for Survival has updated this tradition with apocalyptic fires, COVID-19, alienation from the world, and a rejection of many parts of contemporary Canadian social culture in the hope of finding ones with outcomes that lead to survival instead of social and environmental collapse.

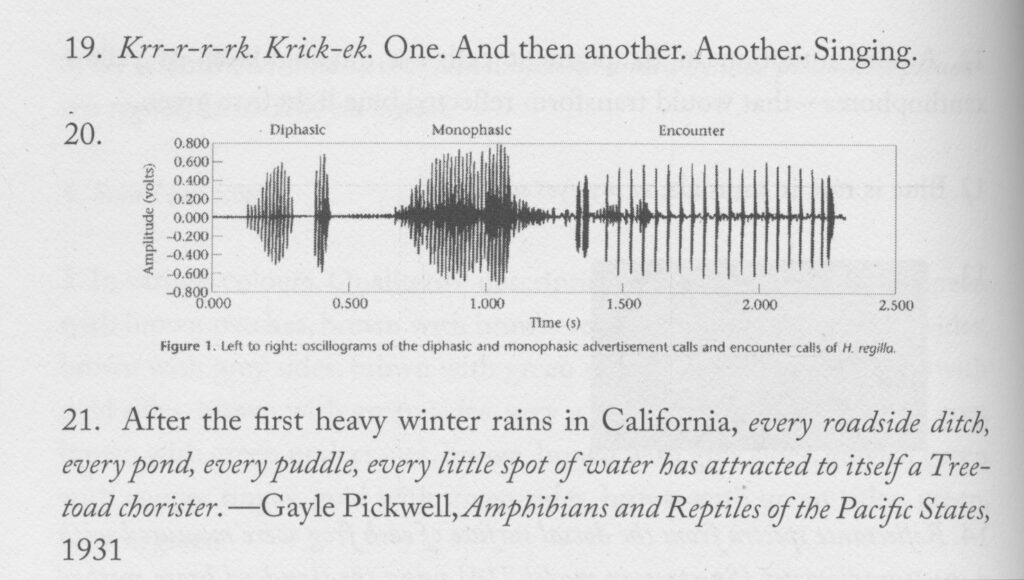

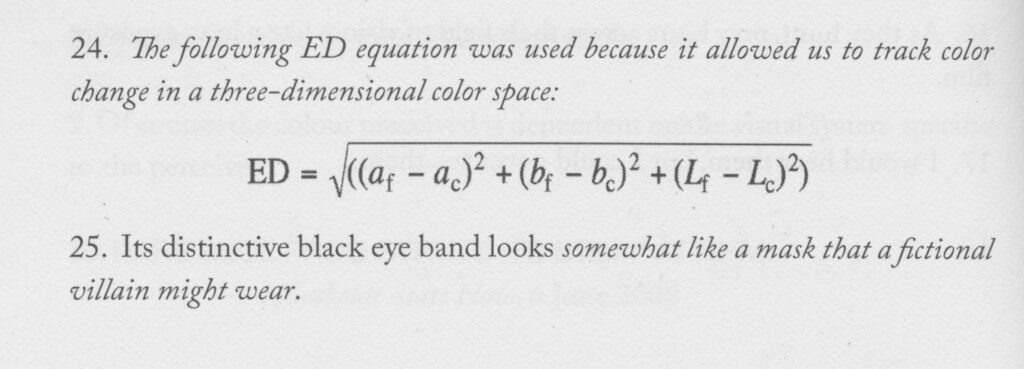

Trainor uses two technologies to pull this off. The first is the Talmudic tradition already mentioned: annotation laid over annotation laid over annotation. The second is through a fierce defence of individuals as observing tools that can notice patterns, record them, and use them to sow self-replicating seeds: life, in other words, that starts with texts and finds the world after that.

In an extension of Mary Shelley’s Dr. Frankenstein creating Rumpelstiltskin’s riddle of life out of bits of corpses, Trainor’s seeds can be DNA sequences, metaphors, or poems. Trainor casts them all into a desert, like Adam and Eve thrown out of the garden for confusing individuality and rebellion.

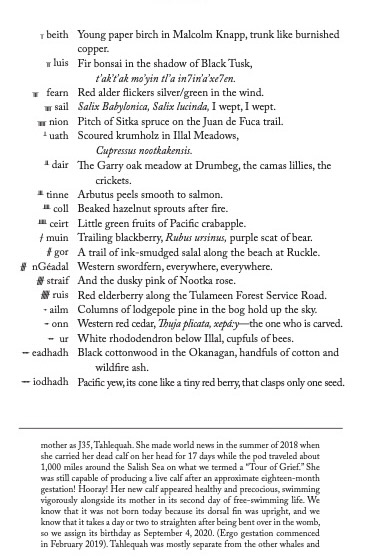

The scenario takes place in the landscape created by settler culture, a cultural fabric which personalizes relationships to land while holding it at a distance. To evade such human-centricism, Trainor embraces communal work, uses her own individual self to observe its own fears of loss in the context of what it is not, and views the apprehension of similarity across difference, the key component of contemporary notions of creativity, to reveal correspondences. It’s here, in “ogam” that emotional excitement shows clearly through this gaze.

Beware, though. That’s a reading of it from a certain distance from Canadian power. My reading takes place from self and place rooted in the Similkameen, the western part of the ancient trail over the mountains from the Skagit country, partly Canadian, partly American, partly Smelqmex, partly métis, and large parts British Empire and German immigrant culture. From that tangled global foundation, Trainor’s work is as much a part of the contemporary popular Zeitgeist as creativity and artificial intelligence, which sorts vast databases according to interlocking sets of difference and similarity, computed not as individuality but as statistical averaging.

With the struggles of my mother in the Similkameen in mind, including her attempts to enter a global world out of local depersonalization, I am troubled. In the settlement of British Columbia, after all, which largely took off in the two decades before World War I, gender came with roles: male rationality and female aestheticism and family care. Women fulfilled those roles as best they could, often with dignity, often with tears, yet left much of the legacy of romanticism’s attachment to place that Trainor is setting aside. I ask only if it is being done too easily.

Among these rejected parts of culture are descriptions of landscape as a means of portraying emotion. Trainor’s “Similkameen,” for example, is mentioned so lightly that it could as easily be “Alice Springs” or “Irkutsk.” They are just words. Fire is the real environment here. The planet is the real locality. Social and geographical space are not. This book about creating place is placeless.

But that’s my reading within global culture. On its own terms, Trainor’s text wants to create life, not place, and looks to a planet without humans. They are present in it as echoes in the last days. The destruction of such imported cultural notions as farms, roads, cities, security, houses and lives that fire wreaks is prefigured by the same destruction in Trainor’s method.

In part, settler culture appears here as fire and pandemic, that scour through the book and the landscapes it sweeps in. From an earth-centric viewpoint, Trainor’s passage through it resembles the view from a car window as it hurtles through from Vancouver to Lethbridge. The road and its endpoints are important. The experience of what lies off of them is privileged by the movement they afford and demand. It’s hard to imagine a Canadian view being otherwise. It’s the nature of the country.

Trainor suggests repopulating the clean slate of a burnt planet with primary forms of life—cells—and building up to a new complexity from there. Environmentally, life can spread through a few resilient species (such as lentils, Pacific tree frogs, and paper birch trees) that can survive a broad range of climates and create conditions for interwoven life.

Trainor counters identification with local culture and geography by placing many of her texts against an ongoing footnote drawn from journals. Personal narratives are broken with scientific notations. Scientific observation is challenged by intrusions of personal life. Each of these strands is fully readable. The sum of them all is, too, although never in a linear, lyrical, or narrative way. You can live in these poems. You can’t read them for story. You can move through them, though, peek into buildings, build houses for yourself even, move into them for a moment, take them down and wander on, just like with a blueprint or a map, those two-dimensional drawings of three-dimensional things.

Trainor’s blueprint is an aesthetic variant: patterning based on recognition of similarity. Take her Penticton (snpintktn), for example, built on a permanent Syilx village in what was once a land and water woven by physical forces, cultural fire, gathering practices and personal responsibilities into a resilient multi-species web that Euro-American settlers didn’t consider cultural or social. They called it (and still do) Nature. It’s that cultural object, not the Syilx weave, and often not even the planet, that is burning.

As an example of the limits of such individual-centred patterning is “Desolation: Two Drafts” (Page 25), a record of a hike in the Skagit watershed:

Then snow. Driving snow

and nothing but the rhythm of the climb up and up until the trail plateaued and

we hit the shuttered fire lookout. Whiteout conditions. Hozomeen somewhere

in the void. I tried to take a photograph, but my phone shut down in the cold.

So, I guess this will have to do. We turned around and began the climb down.

The poem is not about the hike or the industrialized natural landscape above the impounded Skagit. It is about the logistics of getting to the hike, the failure of a hike to provide illumination, and the image of the resulting world being a white out. There is no world there at all. It is a beautiful metaphor for the limits of narrative, humanism and an entire tradition of thought, and it remains part of Apocalypse that Mary and Rumpelstiltskin both set us on long ago and which continue to riddle.

It’s an ancient boundary not easily crossed. The draftswoman over these blueprints is sobbing for connection that reading and writing can only teasingly provide. Only life can do that. The book argues just that.

*

Harold Rhenisch has written thirty-four books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for a memoir, The Wolves at Evelyn. His other grasslands books are Tom Thompson’s Shack and Out of the Interior. He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and worked closely with photographer Chris Harris on Spirit in the Grass, Motherstone, Cariboo Chilcotin Coast, and The Bowron Lakes; and he writes the blog Okanagan-Okanogan. His The Salmon Shanties: A Cascadian Song Cycle will appear this fall. Harold lives in an old Japanese orchard on unceded Syilx Territory above Canim Bay on Okanagan Lake. [Editor’s note: Harold Rhenisch has reviewed books by Dallas Hunt, Tim Bowling, Hamish Ballantyne, Zoë Landale, Kerry Gilbert, Robert Hilles, Sho Yamagushiku, Bradley Peters, Aaron Tucker, Dale Tracy, Dominique Bernier-Cormier, Selina Boan, Joseph Dandurand, Délani Valin, Robert Bringhurst, Rayya Liebich, Sarah de Leeuw, Roger Farr, Stephan Torre, Don Gayton, and Calvin White for BCR. His book Landings was reviewed by Luanne Armstrong; The Tree Whisperer was reviewed by Adrienne Fitzpatrick.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Grim ends, fresh starts”