Fighting for equal status

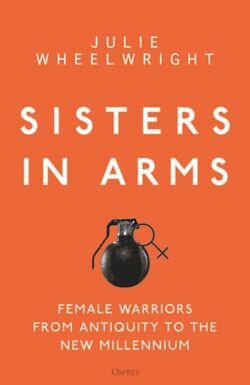

Sisters in Arms: Female Warriors from Antiquity to the New Millennium

by Julie Wheelwright

Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2020

$32.50 / 9781472838001

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

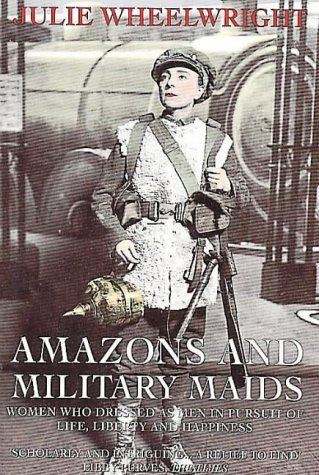

Witnessing a battle re-enactment on the Plains of Abraham, Julie Wheelwright fell into conversation with an IT consultant named Sarah. Sarah was impersonating a farm boy who enlisted in the Kings’ Rangers during the American Revolution. In this and subsequent encounters, she spoke with feeling about the menial role of women in time of war and the continuing opposition to their acceptance and promotion. This is all re-enactment; there is no evidence that the real farm boy was a farm girl. Still, he might have been, and this mattered to Sarah as she acted out what could happen to a girl passing as a male in the army then and now. For Wheelwright the conversations signalled a need to return to earlier research and her first book Amazons and Military Maids: Women who Dressed as Men in Pursuit of Life, Liberty and Happiness, published 15 years previously, in 1989. It would be another 15 years before this updated, expanded, rethought book was completed. Much had happened and keeps happening, and it is by no means clear that the motives suggested in that earlier subtitle still apply. Wheelwright has since written about American and British servicewomen in the Gulf Wars and about female fighters in Sudan and Eritrea. Theoretically and legally women in many countries can now serve in the armed forces in combat on equal status with men, but the equality continues to be compromised by discrimination, belittlement, and abuse.

Julie Wheelwright’s earliest readily googled work was written for UBC’s student publication the Ubyssey in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Based in London, England, she has an affiliation with SFU’s Graduate Liberal Studies program and family connections in the Okanagan. British Columbia makes a brief appearance in this book when Flora Sandes, one of the more memorable characters – and there are many memorable characters – stops at Texada Island before proceeding on adventures which culminate in her fighting in Serbia in 1915.

Why would a woman become a soldier, specifically a male soldier? Some ready answers – escape from a difficult situation, financial security, adventure, service and defence of one’s home and country – sound like the same answers a man might give to the same question. The author explains the book’s plan: “the critical framing is of gender, rather than of biological sex, and through this I explore historic sex-based patterns of oppression and harmful stereotypes”. What matters is less the body in which one was born than the perceptions of that body by oneself and others.

As far as stereotypes go, this reviewer had optimistically assumed we were beginning to overcome them years ago in the 1970s, the age of unisex fashion. Yet in the years since then, and since the publication of Wheelwright’s first book, illusory progress has become entangled in multiple possibilities leading to more complicated and more harmful stereotypes.

The stories Wheelwright tells span many centuries and reveal that the multiplicity has always been there; the narratives become complex, confusing, often distressing and her work part of a “massive and well-researched topic.” The book tries to be clearly organized, from introductory chapters and “the founding myth of the Amazons” through the stages of enlisting, living among the men, discovery or not, back to Civvy Street, and then what happened next, what is still happening. Wheelwright unfolds the history via the life stories of real people, the problem being that neither the stories nor the people lend themselves to clarity or to chronological order, and the concept of gender identity only becomes more complicated the more we study it.

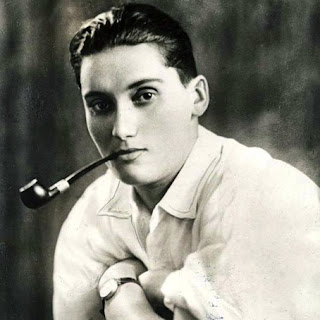

Take, for example, one of her most fascinating characters, Col. Victor Barker, a.k.a. Valerie Arkell-Smith. When we meet them at the beginning of Chapter One, it is 1923 and they are being married to Elfrida. A hundred pages later, we find that Valerie had originally adopted male disguise to escape an abusive relationship. She was exhilarated at how easily she got away with her military persona and “became more and more daring.” The author comments that “women often report the benefits of male clothing that allowed them greater physical freedom, unencumbered by restricting items, and the licence to roam freely to previously forbidden places, even at night, where they had access to new pleasures.” But Barker’s form of masculinity was “linked to violent extremism” and they became part of the most militant element of British fascism. Once the victim of social structures which enabled domestic abuse, he “allied himself with the most hierarchical, authoritarian, racist and hyper-masculine ideology of his era.” Another hundred pages finds Barker as menial labourer, petty thief, domestic servant, and by the end of the 1930s, a featured attraction in a Blackpool freak show. For a time, people were interested in reading his story in popular magazines, but that interest faded, and his tragic life dragged on for another 30 years. Multi-talented and physically attractive, he, or she, was a disaster.

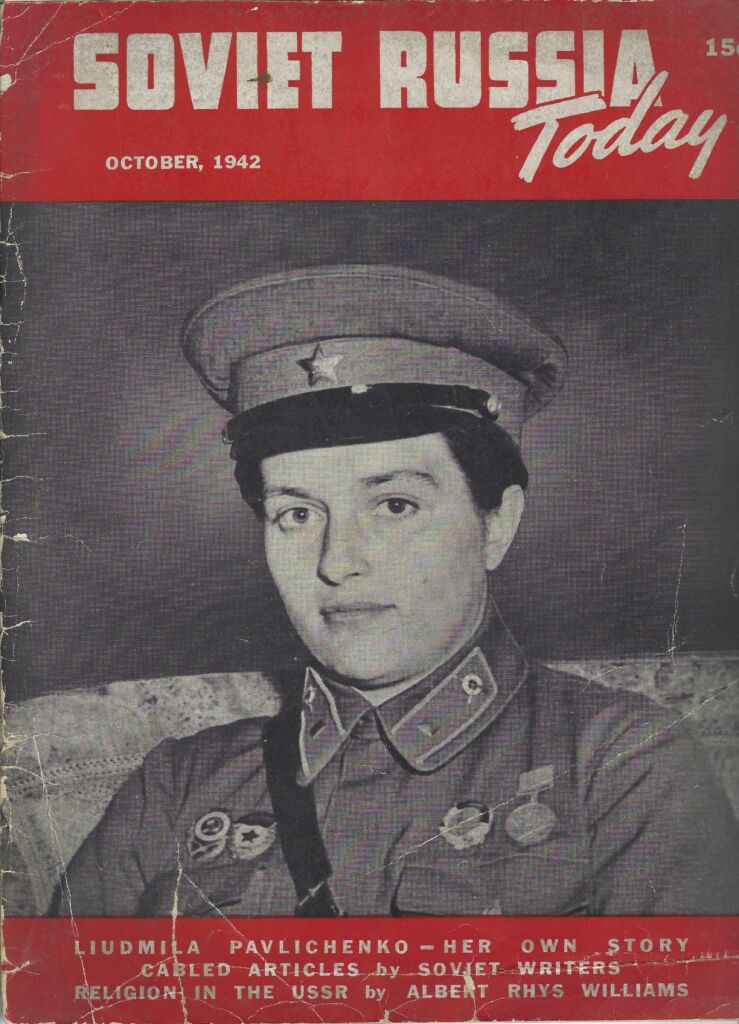

Victor/Valerie may be the most lurid of Wheelwright’s case studies, but there are others, to name a few: Hannah Snell of the Royal Marines; Deborah Sampson, soldier in the American Revolution; the pirates Mary Read and Anne Bonny; journalist Dorothy Lawrence a.k.a. Private Dennis Smith on the Western Front in 1915; the Cossack Marina Yurlock; the Russian guerilla Lyudmela Pavlichenko who visited Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House; the Republican senator Martha McSally who commanded the USAF 354th Squadron in 2004 and later testified before an armed services committee about the physical and psychological consequences of sexual abuses within the military. Their stories and many more weave through the book as times and topics suggest.

In this second book, Wheelwright’s female warriors no longer necessarily disguise themselves as men. She tells us The Amazons “were actually women of Scythian society who lived amongst their men and were raised as equals.” Joan of Arc did not pretend to be a man. Both sides in the English Civil War included women as foot soldiers or troopers. During the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars the femmes soldats enjoyed “a brief moment of access to male occupations and privileges” before purged by the Jacobins as “insulting to men and undermining of male physical superiority.” But the femmes did not all fade away into “a mere extension of military wife or daughter; traces of the soldat remained in their political influence among their generation and visions of a new form of equal citizenship. The story of the sisters Felicite and Theophile de Fernig is another of Wheelwright’s stirring narratives. Women reappeared prominently on the barricades of the Paris commune; they were not easily kept down on the farm.

Anna Leonowens, of The King and I, wrote about the bodyguard of “Amazons” at the court of Siam. Other travellers encountered the female elite corps at the African court of Dahomey. In America, tales of female combatants circulated through Union and Confederate armies, meeting with scepticism but circulating nonetheless. During the Serbo-Turkish War in 1876, the outspoken aristocrat known as Mademoiselle Milokovitch exclaimed: “your greedy sex monopolised all the sensible occupations and left us poor women nothing by nursing and needlework.”

Russian women appeared prominently on various battlefields with varying allegiances. During the First World War, Maria Leont’evna Bochkareva led her own battalion, the 1st Russian Women’s Battalion of Death. Before her military career, she exemplified gender equality in non-military arenas, for instance as assistant foreman on a construction site. Again, the reader may find themselves sympathising with unlikely characters, an unexpected exercise in empathy.

By the Second World War, British women were deployed not only in secretarial, intelligence, or chauffeur work, but in flying prototype planes and other activities likely to be considered masculine.

Writing about the Auxiliary Territorial Services, Wheelwright mentions Mary Churchill introducing her father to her battalion, but says nothing of Mary’s sister-in-arms Princess Elizabeth. Nowhere in the book is there reference to the first Elizabeth exhorting her troops: “I know I have the body but of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too” and promising that if necessary “I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.”

However, while Mary Churchill and Elizabeth Windsor were “officially members of the armed services,” they and their comrades were neither recognised nor rewarded equally with the men.

Through the Cold War, Korea and Vietnam little changed and there seemed even fewer opportunities for women than during WW2. In the USA, the introduction of an all-volunteer army coincided with second-wave feminism and a decline in the male draft pool. Since the year 2000 women, not disguised as men, have increasingly participated in combat in Iraq, Afghanistan, Bosnia, and the Middle East, and achieved high level rank. The rumored favourite to be appointed the next chief of Canada’s defence staff is Lieutenant-General Jennie Carignan.

With her focus on “the women in auxiliary services and combat roles from the 1930s to the new millennium,” Wheelwright finds her material and historical continuities in “the experiences of servicewomen in Britain, the United States, the Soviet Union and Russia.” The rules have changed, but perceptions in the field have not caught up. A warrior perceived as of female gender continues to be perceived as fair game; for American women soldiers in Iraq the threat of sexual assault came more from their own troops than from the enemy.

Throughout the book, Wheelwright worries about the internal conflicts, contradictions, and traps which her subjects face in their life among the men and then in the wider world. What became of comradeship? Same-sex friendships? Loves? As the female fighter proved herself, her bodily differences became irrelevant and her identity as a soldier was complete, but was the price “sexual erasure?”

After the battle, what was to become of them? No one knew. For many of these female warriors the return to womanhood was “fraught with difficulties” and routine women’s work a “demotion,” a loss of hard-earned authority and power. They might be veterans in fact, but without benefit of pension or recognition of their heroism, or participation in the spoils of war. On the other hand, continuing life in male disguise meant years of evading detection, with no likely happy outcome. Witness the elderly veteran of the American Civil War who was discovered to be a woman, forced to wear a dress for the first time in 40 years, tripped on his skirts, broke a hip, and died 6 months later. The good news is that former comrades and employers insisted he be buried with full military honours.

Veterans might choose to publicise their dual identities and tell their stories as long as anyone wanted to listen: “The publicity that came from a memoir, theatrical performance or charitable venture served to enhance the female veteran’s social reputation and provide vital income, especially for those suffering from war-related injuries and illness.” But this could put them on display as something “novel,” their military achievements “ignored or trivialised,” a freak show like Col. Valerie.

The Russian state after Perestroika revered women’s important role as mothers morally superior to men. Today’s Russian women may enter combat as “proxies for inadequate men.” Some have become Facebook icons. Lest anyone imagine a world defended by sisters-in-arms would radiate sweetness and light, consider the career of Yulia Kharlamova, Ukrainian fascist and “good Russian patriot.” Telling Yulia’s story, Wheelwright points to an unnerving trend in the use of social media: “a terrifying new form of warfare in which women engage in espionage, subversion, even terrorism to attain their leader’s political ends. Rather than actively participating in civic life or going adventuring like the earlier Amazons, these women seem trapped in hyper-feminine roles where they must remain attractive, available and good with a gun.” The old stereotypes twisted into post-apocalyptic cyber-beings.

In an era of confusion and anxiety over gender roles, Wheelwright has given her readers much to ponder. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, disguise and cross-dressing were subjects of study by the likes of A.J. Munby, Richard von Krafft-Ebbing and Magnus Hirschfield, with rumoured encounters in Victorian London, codes of feminine behaviour, whispers of “deviancy,” chatter about same-sex comradeship and something called the “erotic enlightenment movement.” The claim that “equality between the sexes rendered male disguise redundant” gets short shrift; what if one wants to wear male disguise? The book is about women who pass as men and fight alongside men; there is nothing explicitly about transgender persons in a wider sense. Nevertheless, I found it impossible not to think of the current LGTBQ+ community and wonder what life would be like if everyone stopped viewing everyone else and themselves through a stereotypical lens. But such moralising comes from the reviewer, not the author.

Dispassionate, not polemic, not advocating, accessible but scholarly (with 70 pages of notes, bibliography, and index), Wheelwright’s book is the sort of contribution we need to our worried public discourse on gender and identity and women’s ages-long negotiation for their equal right to nurture and to kill.

Meanwhile, Denmark is planning to conscript women for military service, so a woman might have to become a warrior whether or not she wants to. As always, one should be careful what one wishes for.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve was born in Fiji, grew up in Quebec, and has lived most of her life in British Columbia. Her most recent publication, in Dorchester Review #25 (Spring/ Summer 2023) revisits the history of pre-colonial Fiji in the writings of her paternal grandmother Richenda Parham. Editor’s note: Phyllis Reeve has recently reviewed books by Rika Ruebsaat, Doug Harrison, Dave and Rosemary Neads, Robert G. Allan, Mother Tongue Publishing, and Lara Campbell, Michael Dawson, & Catherine Gidney for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Fighting for equal status”

I found this a brilliant review of Wheelwright’s book, which I read shortly after publication. The book is packed full of stories, each story unique and fascinating. The reviewer succinctly told them all. A great book and a great review.