A father’s secrets

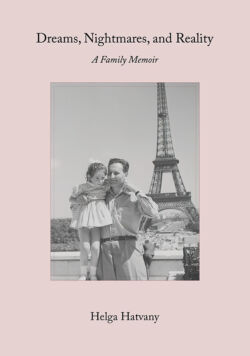

Dreams, Nightmares, and Reality – A Family Memoir

by Helga Hatvany

Virginia: Mascot Books, 2022

$23.63 / 9781645439820

Reviewed by Peter Hay

*

Helga Hatvany comes from one of the most prominent families of Jewish origin in Hungary. Her ancestor Abraham Deutsch began the family grain business during the Napoleonic wars, and his son Ignac turned it into a major crop trading enterprise in central Europe. Eventually, Ignac expanded into building steam mills and buying arable land. One of his last acquisitions was a country seat in the district of Hatvan, north east of Budapest, which the family later adopted as its Hungaricized name.

The transformation from Deutsch to Hatvani-Deutsch to Baron Hatvany mirrors the rise in wealth and influence by Jews from the Enlightenment of the late 18th century to the twilight of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy in the early 20th. During the last fifty years of the dual monarchy, before its defeat at the end of the First World War, some two hundred Jewish families were ennobled or granted baronial titles by the emperor Francis Joseph.

In the 20th century many members of these families formed the core of intellectual and artistic life in Vienna and Budapest. Helga’s grandfather, Bertalan Hatvany, was a writer and oriental scholar who translated from Chinese. His cousin Lajos, probably the best-known Hatvany, at least in Hungary, was a litterateur and patron of the arts; he co-founded and financed the leading literary magazine in the early 20th century, called Nyugat (West). And Helga’s great-aunt, Lili Hatvany, wrote a number of successful comedies before emigrating to America just before the Second World War where her plays were adapted for Broadway and Hollywood.

The focus of Helga’s memoir is her lesser-known scientist father, József Hatvany (1926-1987), whose achievements have a far greater relevance to our world today. He was an early pioneer of robotics in Europe, inventing and developing tools for digital computers to program machines and control production. His patented inventions eventually led to such familiar programs as computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM).

The intellectual path to his career was far from smooth or predictable. With the rise of Nazism in Germany and Austria, the doors of opportunity were closing years before the destruction of European Jewry. In 1920, Hungary became the earliest state to legislate a quota system – the so-called numerus clausus – which restricted entry for Jewish students to universities, especially in medicine and law. By 1910, some 60% of these professions were dominated by Jewish practitioners, a proportion ten times higher than Jews in the general population. In some circles, the Hungarian capital had acquired the moniker of Judapest.

Some members of the Hatvany family, including Helga’s grandparents Bertalan and Vera, could read the warning signs of these restrictions and had the means to leave Hungary. In 1938, they sent their son, aged twelve, off to England to be educated at a boarding school where he perfected his English. From there he secured a place at Trinity College, Cambridge, one of the main centres for physics, mathematics, and philosophy in the English-speaking world.

Cambridge at the time was also a hotbed of idealistic Communism where Anthony Blunt, a fellow of Trinity College, was busy recruiting undergraduates to spy for the Soviet Union. Young József wasn’t one of them, but he was excited about the possibilities opening up in his homeland, after it was liberated from the Germans by Soviet troops. Politics distracted him from his studies and he failed his final exams in 1947. By that time József was in a hurry to return to Hungary. His like-minded girlfriend and future bride, the Scottish Doris Eldrick, went with him.

After an absence of nine years, the 21-year-old young man threw himself into rebuilding his almost totally destroyed country. He went to study Marxist economics at the Communist Party School, and was soon teaching it at university level. With his English language skills, he also got a job with the Foreign Language Department of the Hungarian radio. When the Communist Party seized power in 1948, the future seemed bright. It was not to last. With the cold war dividing the world into East and West blocs, a wave of arrests swept through the Communist countries leading to the purge and infamous show trials of loyal, idealistic party members.

Given his many contacts with English friends from college and members of his famous family living abroad, József was particularly vulnerable. He was first removed from his job at the radio, where the entire foreign language unit was arrested. An early wave of the show trials in Hungary involved groups of British and American engineers who were helping to rebuild the electrical infrastructure destroyed in the war. The interrogators needed interpreters for the accused and József was assigned to be one. But as the purges gained momentum, he too was arrested in 1952. Subjected to brutal physical and psychological interrogation – with methods immortalised by Arthur Koestler in his 1940 classic, Darkness at Noon – Hatvany confessed to fabricated charges of spying at his secret trial, and was sentenced to 11 years of imprisonment.

Following Stalin’s death in 1953, most political prisoners were released, but it took another three years for Hatvany to gain his freedom. Part of the reason was the useful scientific work he and other convicted engineers were performing, without pay, of course, but it helped to keep their sanity. When József was released in the summer of 1956, he found recognition for his work in the scientific community, but the rest of his life was in tatters. Under pressure Doris had divorced him, and he literally lacked for everything, including clothes and shelter.

The Hungarian revolution broke out a few weeks after his release, and before it was swiftly suppressed by Soviet tanks, the border with Austria lay open. Many former prisoners escaped to rebuild their lives in the West. József Hatvany waited too long and, captured at the border, was returned to prison where he spent another year. House arrest followed until he was granted amnesty in 1960. He resumed his research work at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, where he met and married one of the secretaries, Zsofia, the author’s mother.

Regaining his freedom did not really set József Hatvany free, because the whole country was a prison behind the Iron Curtain. However, he was gradually allowed to attend international conferences, and even take his wife and daughter abroad, where he visited the scattered and alienated members of his family. His parents begged him to defect and stay in the West but, curiously, József always returned to Budapest. Helga suspects, after she uncovered evidence that her father did some industrial spying about the latest scientific advances abroad, that this activity – by no means uncommon then or now – had won him privileges back at home.

József Hatvany did not live to see the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of its domination of Eastern Europe; he died of leukemia in 1987, and one cannot be sure that he would have welcomed the change. He had come to terms with the country that held him captive, while his fame grew in scientific circles around the globe. In many ways he was already living in the future when computers and robotics would come to dominate our lives. He had the foresight to talk and write about the social challenges of automation that have now caught up with us two generations later.

Much of this memoir is about a daughter’s obsessive search for her father’s secrets in his political, professional, and personal life. Because of the times and the places József Hatvany inhabited, the book also provides a geopolitical context for some of the core conflicts of the mid-20th century.

Helga herself found freedom, not with the wall crumbling in Berlin, but when her father died. She married an American and re-established her own contacts with her far-flung family. She has wandered the globe, including Vancouver, where most of the book was written. And much as we learn about her childhood and growing up, much more is left out about the adult she has become. I am hoping for a sequel that is likely to be as insightful and readable as her first book.

*

Editor’s Note: Here are some personal disclosures from Peter Hay, as a postscript to his review –

Like József Hatvany, I was born in Budapest and was sent, also at the age of twelve, to England, where I was educated in boarding schools and at Oxford. I didn’t see my parents again until I was nineteen: they chose to stay behind and face the consequences of the failed Hungarian revolution of 1956. My father, also a lifelong idealistic Communist, was arrested and imprisoned in Marianosztra, the prison where József Hatvany suffered; I don’t know if they ever met there.

When I was working on my first book about Chana Szenes, Israel’s national heroine, I found out almost accidentally that ‘the Baroness’ held prisoner by the Gestapo with Chana and her mother, Catherine, was Elisabeth Marton, the legendary New York agent who then represented my father’s plays, and who had been married at one point to Baron Lajos Hatvany.

It took me a long time, after I read this memoir, to sort out my feelings. Not my thoughts which found much of it new and interesting about a distinguished family I barely knew about. It was the author’s search and research that stirred up familiar memories and connections to a lost homeland – to people who were close and now are gone.

*

Peter Hay is the author of ten books and now lives in the Okanagan Valley.

[Editor’s note: Peter Hay has also reviewed books by Judy Piercey, Timothy Christian, Joe Gold and Robert Krell for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster