Growth from lawlessness

The Notorious Georges: Crime and Community in British Columbia’s Northern Interior, 1909 – 1925

by Jonathan Swainger

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2023

$32.95 / 9780774869416

Reviewed by Steven Brown

*

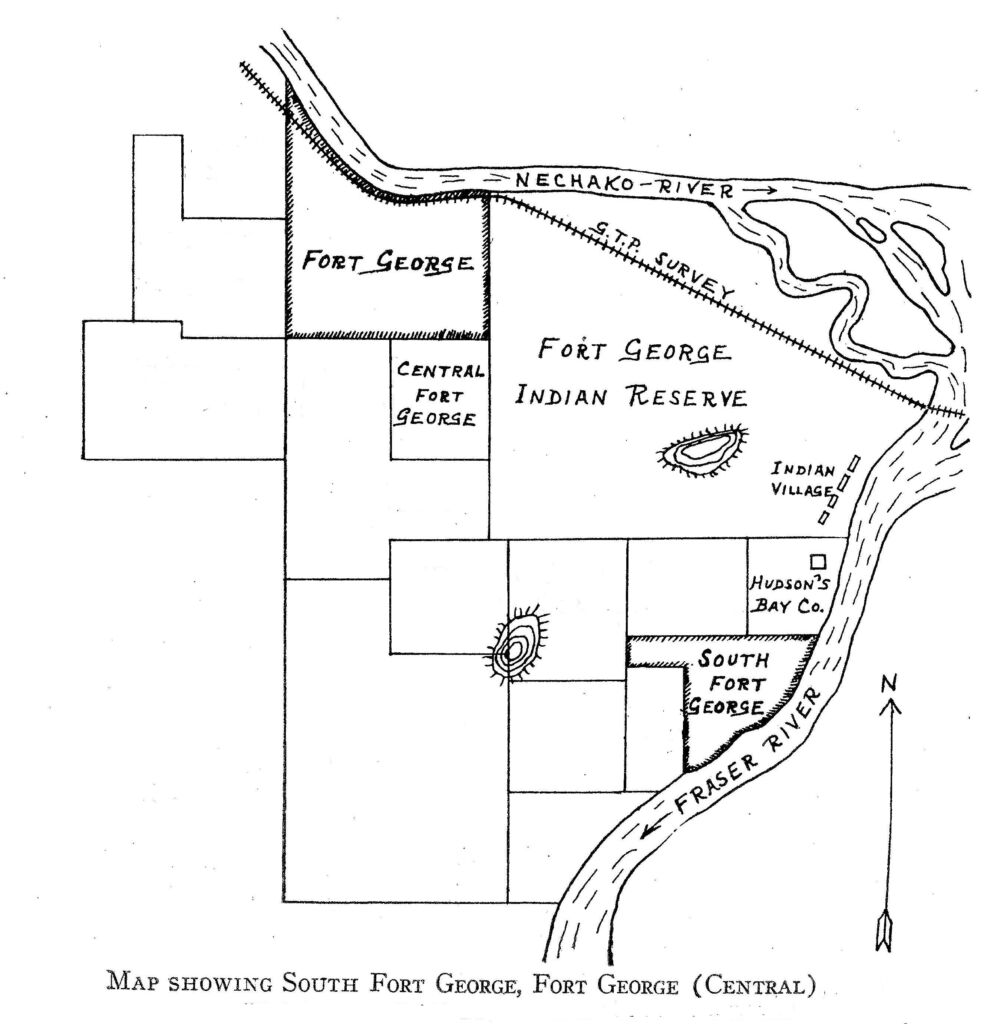

The potential real estate value of land around the confluence of the Nechako and Fraser Rivers was recognized in the early years of the twentieth century. This was largely due to the proposed Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (GTP) line that would be coming through the area connecting from Prince Rupert on the north Pacific coast to points east as far away as Ontario. The only catch was that one of four Lheidli T’enneh First Nations reserves situated south of the banks of the Nechako and west of the Fraser occupied a large part of the area. The railway survey ran right through the reserve. Lheidli from the Band’s own website means, in the Carrier language, “The People From the Confluence of the River.” “T’enneh” literally means, “The People.”

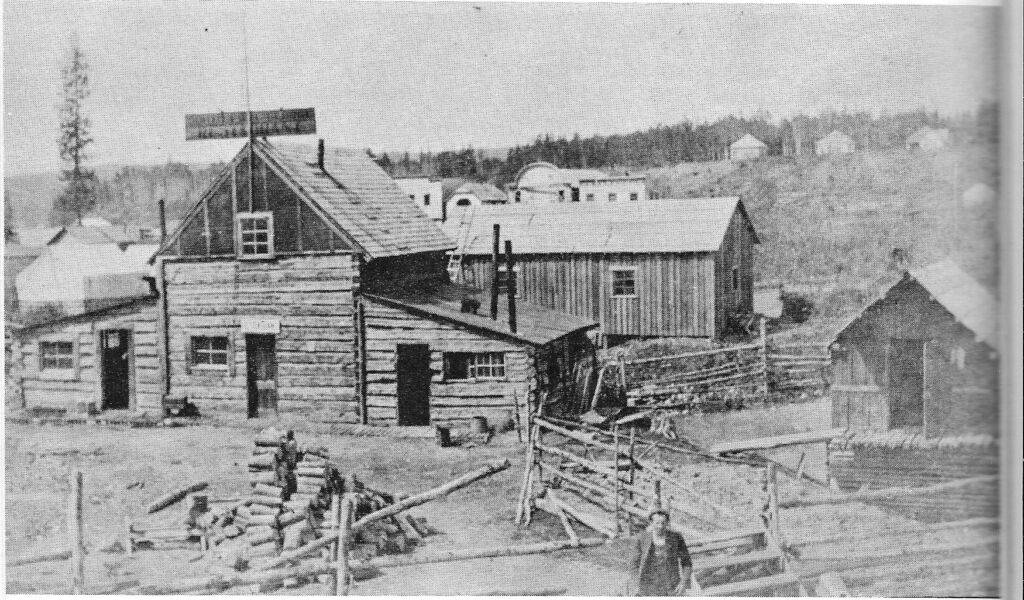

The fact of the reserve being where it was didn’t stop white settlement. It didn’t matter that the the Lheidli T’enneh had occupied the region for millennia. The perception was the current situation would be resolved in development’s favour at some point. A section of land immediately west of the reserve, Fort George, had originally been the site of a fur trading post established by Simon Fraser in 1807. Agricultural initiatives gradually grew up around it. Much later South Fort George, the regions first bona fide white settlement, grew up around A.G. Hamilton’s general store which opened for business in 1906. It was south of the reserve and directly south of the the Hudson’s Bay Company outpost whose patch of ground bordered the southern edge of the reserve.

British Columbia, established as Canada’s sixth province in 1871, included the vast area of the central interior. Except for the native population, the region had been sparsely populated by white settlers. The railway coming towards the river confluence and the two Georges was likely to provide many opportunities for business and growth. Rivalry grew intense between residents of the communities over which location would be the sight of the new GNP station. As things turned out neither would be. The railway after protracted negotiations offered the Lheidli T’enneh a hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars to vacate their reserve which their chief “reluctantly” accepted and the train station was to be erected in the newly created city of Prince George on the site of the former reserve.

The Notorious Georges is about the rivalry of the two Georges and about the founding of Prince George. It’s also about the drive to tame a wild land with organized townsites and laws, rules, and regulations that needed to be adhered to—civilization as opposed to lawless wilderness. It’s published by UBC Press for the Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History and is an addition to UBC Press’s Law and Society series. Scholar and University of Northern British Columbia history professor Jonathan Swainger states his intention in his introduction was to write an accessible and engaging work that seeks a wider audience than might be typical for a piece of scholarly research. In this he has admirably succeeded. There’s a lot of compelling history about the region as there is about all of British Columbia and a lot of it is not widely known. Anyone coming to this book has made a good start.

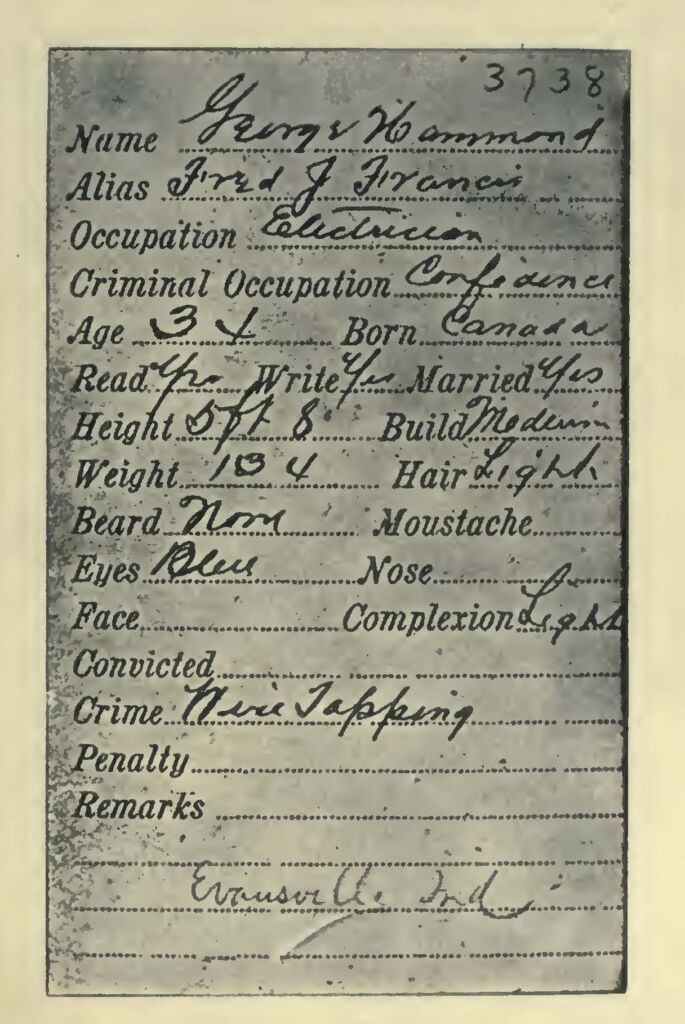

Before the arrival of the railway, the two Georges had developed unsavory reputations. The halls of the provincial government were far away in Victoria and Vancouver, there was no local law enforcement, liquor flowed freely, there was gambling, and a house of prostitution was never far away. The fallout from incidents of obnoxious behaviour and street brawling, things that while not in reality anything worse or more common than some of what went on in many other BC communities before the First World War stuck fast to the Georges as the population grew. An exacerbating factor was the “devil-may-care exploits” of some of the early movers and shakers in the communities who equated self-interest with the public good as well as rival newspapers in Fort George and South Fort George that sensationalized incidents out of proportion to fact.

In those days British Columbia was unreservedly a white man’s province and racist attitudes to anyone who wasn’t white were the norm. If you were Indigenous, Chinese or black (and Prince George did have a small black community), or, worst of all, a “half-breed,” you were a tolerated and, perhaps, in some way, useful non-entity but there was no question about your status in the community. Unsurprisingly, whatever skullduggery or bad behaviour was laid at the door of the non-entities was being perpetrated almost wholly by white men. As the author states, “Simply put, the whole of British Columbia was a boozy, truculent and unapologetically racist place well into the 1930s.”

In 1911, the Lheidli T’enneh began their removal to a habitation named Shelley up the Fraser River from their former reserve which itself had only been established in 1883. The site of Prince George was subsequentially laid out. Incorporation followed in 1915. Charles M. Hays, president of the Grand Trunk Pacific, was determined to cut Fort George and South Fort George out of any big financial benefit from the establishment of the railway. He wanted the railway to be the chief beneficiary of commerce. Positioning his station in a brand new townsite would go a long way to ensuring that. However, expectations that the new railway would be a money maker didn’t pan out. Insufficient traffic bankrupted the GNP in 1919. The line was taken over by Canadian National Railway.

Law enforcement. Yes. This was another perception that developed, that the law needed to be here. The British Columbia Provincial Police (disbanded 1950) had been around since 1858. South Fort George gained one BCPP constable in 1910, the same year the provincial Liquor Act became law. No one in the area had obtained a license but the market for liquor didn’t go away. The Northern Hotel when it opened in South Fort George managed to secure a liquor license and sported a ninety-four foot bar with twelve bartenders. The place was usually packed. The hotel burned down but was rebuilt.

The first constable in South Fort George, Frederick Gosby, didn’t last long. He couldn’t get paid what he felt he was worth and quit to become a fisheries inspector. Another lone constable was brought in but didn’t last long either before a promotion sent him to Hazelton. The size of the police force doubled to two men after that. A temporary jail had been constructed on the Hudson’s Bay Company land. Sheds borrowed from the approaching railway project were used as “detention” sheds in both Fort George and South Fort George.

Newly incorporated Prince George established its own police force. This didn’t deter the BCPP from having a presence too which generated confusion as to who was to do what. The BCPP represented provincial government authority and their members in Prince George aside from office work did very little actual policing. The war reduced the number of people needing policing and the number of police. The reduction in police numbers was halted by the introduction in 1917 of prohibition in British Columbia. Prohibition wasn’t much loved by the populace and not much adhered to whenever possible but the job of the police was to enforce the law. Prohibition, having created more problems than it solved, was repealed in 1921. The provincial government took over the liquor business, instituting a monopoly. If you bought liquor in British Columbia by law it had to come through the government who collected a tax on every bottle.

The author takes deep dives into the primary sources of the local newspapers of the time for a great deal of his material, The Fort George Tribune, the “combative” Fort George Herald in South Fort George and the Prince George Citizen, detailing the rocky road of Prince George governance and of policing as affected by men with local authority who often were amateurs or just plain incompetent. Mayoralty was for one year terms which wasn’t an aid to progress or stability. There was the war and the global Spanish Flu epidemic, 70% of whose victims in the Prince George area were First Nations.

Distance from the centres of power in the province resulted in what the author calls a sense of “mulishness” in the attitude of Prince George to those centres of power. The feeling was one of a lack of respect and of being dictated to by people who thought they knew what was best for the locals on the far away, not-especially-important frontier. There was upset over the fine government building that had been built in Prince Rupert in 1921 and the same not being planned for Prince George. This mulishness continued but the city endured. It’s quite a story and quite a complicated one. Dr. Swainger has done a masterful job organizing a mountain of material into a coherent and very interesting saga.

In my own deficient knowledge of BC history, for instance, I was unaware there’d been sternwheelers on the upper Fraser River and connected bodies of water as far north as Takla Lake north of Vanderhoof all the way down to Soda Creek south of Quesnel, as well freight laden “scows” piloted by doughty males steering with long poles. It sounds potentially perilous as well as terribly grand and romantic. I was shocked.

*

“Books have ruined my life,” jokes Steven Brown. A professional in the book trade for years he’s managed to retain a deep and abiding passion for good books and first rate literature. He was born in Saskatchewan and grew up in Ontario and British Columbia. Vancouver is home these days. His reviews have appeared in Canadian newspapers, a literary review or two and he has donated reviews to good causes. [Editor’s note: Steven has reviewed books by Bruce McLellan, Gail Anderson-Dargatz, Patrik Sampler, Taslim Burkowicz, and Rhonda Waterfall.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster