Emerging from vulnerability

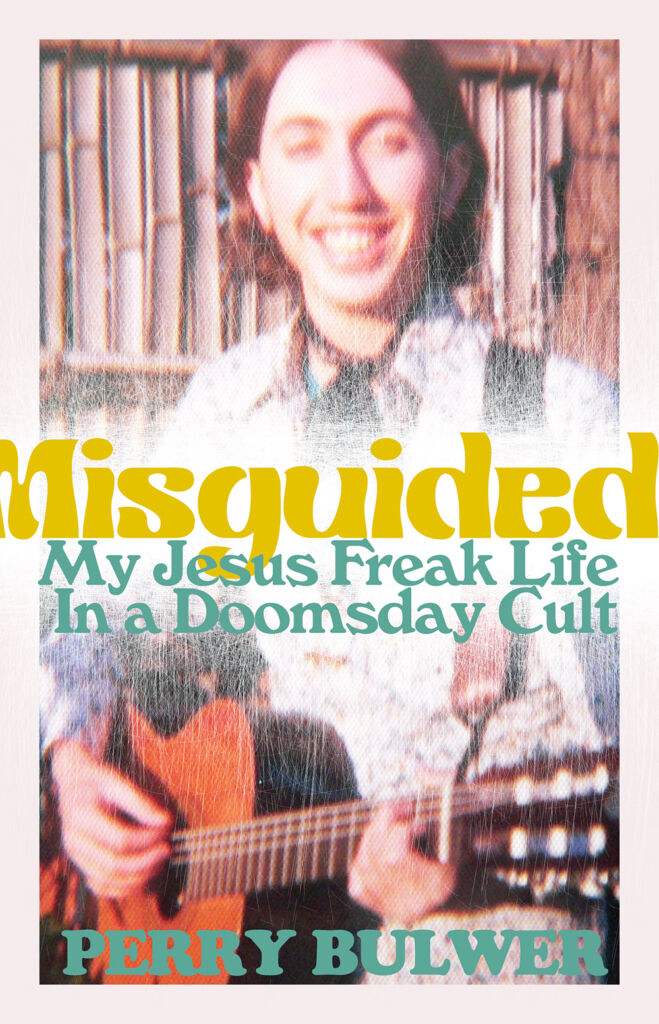

Misguided: My Jesus Freak Life in a Doomsday Cult

by Perry Bulwer

Vancouver: New Star Books, 2023

$26 / 9781554202058

Reviewed by Ryan Mitchell

*

Perry Bulwer’s Misguided describes his decade-spanning journey of joining and eventually abandoning the Children of God (C.O.G.) cult on 1960s Vancouver Island. A shy teen without a dedicated support network, Bulwer succumbs to peer pressures and becomes withdrawn from school and his family. Encountering a pair of proselytizers at a local diner in his hometown, they engage him in a thought-provoking conversation about faith, and soon after invite him to their commune. Bulwer’s recounting of the events that would lead him into the ‘Family’, are remarkably detailed and candid. Writing his story years after having left the cult for good, he contextualizes his decisions and emotional state throughout his indoctrination. The book forms both a personal case study in the psychology of how vulnerable individuals are susceptible to cults, and how destructive to one’s worldview it can be trying to leave one.

Bulwer describes his upbringing as emotionally stunted, leading him to search for acceptance in others. He did not have any mentors, real friends, hobbies, or much social skill development; leading him to spend most time alone, increasing his alienation from his peers. Bulwer’s school did not offer a world religions class, and failed to teach the critical-thinking skills that he suggests may have prevented his indoctrination. Once Bulwer begins spending most of his free time with the cult members, his parents arrange a talk with the family church’s pastor. This ironically only solidifies Bulwer’s interest in joining the group, as the pastor is shown to be open-minded to many of the C.O.G. and the group’s efforts in principle.

Bulwer balances recountings of his personal experiences with the C.O.G., with depictions of the group in the media at the time. He explains how they preyed on the uncertainty and naivety of its youngest members, claiming they helped turn youth away from drug addiction and criminal behavior, stories frequently embellished or fabricated to gain public sympathy. Bulwer relates the media panic covering the rise in teenage-runaways at this time, which the C.O.G. capitalized on to present their communal religious lifestyle as a preferable alternative for the children of nervous parents.

By the end of 1973, Bulwer states over 2,000 C.O.G. members were present in 40 countries, living in 140 communes. Self-appointed C.O.G. leader David Berg declared himself the prophet of the group within 4 years of founding it, and through a combination of literal biblical interpretation and his personal opinions, predicted Jesus’ second coming in 1993. Berg announced the C.O.G. efforts to spread to Southern and Eastern continents due to America’s supposed ‘imminent destruction’ due to its supposed sinful trajectory. Coincidentally, Berg along with other high-ranking members of the C.O.G. hierarchy were constantly moving to evade authorities, the media, and deflect criticisms from within the group itself. Bulwer was transferred from communes in Seoul, to Tokyo, then Manila; facing occasional trouble with police for not having proper documentation.

Throughout the book, Bulwer includes excerpts from proclamations by the C.O.G. leader, which were avidly read in the group’s communes. Berg’s proclamations covered all topics from proselytizing to permitted sexual activity, and conveniently parroted his own self-interests as he worked to promote “flirty fishing”, a manner of influencing non-members into benefiting the group by using sexual advances.

Bulwer’s missions proselytizing for the C.O.G. in foreign countries also allowed him to be exposed to other cultures, lifestyles and languages than he likely ever would have known had he remained in Port Alberni. However, his travels were never unrestricted; for one, the Family prohibited visiting man-made attractions such as the Great Wall of China, considered blasphemous and contrary to the spiritual importance of God. Despite this, particularly in his early years with the church, Bulwer often found himself able to travel alone and occasionally have private use of apartments while his preaching partners were out. After being discovered engaging in some intimate relationships with non-Family members, the C.O.G. reprimands Bulwer for his disobedience and began monitoring his activities much more closely, causing him some understandable paranoia.

After returning to Canada to live with his family, Bulwer decides to leave C.O.G. for some time and works odd jobs, but is unable to fully integrate back into society and retains beliefs in certain C.O.G. teachings (including the Doomsday prophecy). Faced with few professional prospects, lack of social skills or formal education past a high school level, a run-in with members of the group leads Bulwer back into the same church he previously abandoned. Bulwer eventually takes on a job teaching English at a Chinese university (through forged paperwork provided by another C.O.G. member), while technically still being a high school dropout. Bulwer describes his slow fallout with the C.O.G.; expressing doubts in secret, noting the hypocrisy of the leader’s actions, group humiliations, and physical abuse particularly of its youngest members. As the C.O.G. practices left him spiritually, socially, financially, and psychologically dependent on the Family, Bulwer illustrates his tremendous fear and agitation to leave permanently.

Readers will be interested in the book’s insight into cults from a non-academic insider’s perspective with lived experience. Bulwer writes with compassion for other members of the cult who were forced into circumstances they did not understand or could not control. He also openly writes with disdain about the movement’s leaders who upheld the practices and methods of the group for decades. Bulwer’s transformation throughout the book is self-evident; he starts as a naive youth yearning for life’s answers through any means, then as a mature adult becomes an activist in the judicial system aiming to protect the vulnerable (sex workers, unhoused people, and addicts) in his community of East Hastings in Vancouver. He also attempts to connect with other ex-members of the C.O.G. to archive their stories and perspectives. Parallels can be drawn with Bulwer’s dedication to fighting for at-risk communities and his own former existence on the fringe of society that led to his indoctrination.

*

Ryan Mitchell is an avid reader and part-time editor passionate about people’s stories, history, film, and cities. His background is in sociology and urban studies, and he enjoys volunteering with local cycling initiatives, film, and street festivals. In recent years, he gained experience as an editor for a UN-sponsored NGO called AlterContacts: Lockdown Economy, archiving small-business experiences facing the challenges of the pandemic. He has studied the gentrification of Amsterdam’s De Wallen neighbourhood (also known as the Red-Light District), and covered the grassroots community-planning movement preserving Toronto’s historic Kensington Market neighbourhood. An Ontarian now based in Vancouver, Ryan enjoys exploring the rainy coast of BC and the Pacific Northwest and is working to become a city planner. [Editor’s Note: Ryan Mitchell has previously reviewed books by Mary Soderstrom and Tamar Glouberman]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Emerging from vulnerability”