A studio by the lake

E.J. Hughes: Life at the Lake

by Robert Amos

Victoria: Touchwood Editions, 2023

$25.00 / 9781771514194

Reviewed by Christina Johnson-Dean

*

Ah….. life at the lake! For so many of us that simple phrase evokes memories of happy times, relaxation, peacefulness, a break from routine, school, codes of behaviour. And as we look forward, there’s the anticipation of being with the ones we love, enjoying a respite from city life, work, and expectations. For painter Edward John Hughes (1913-2007) Shawnigan Lake, just north of Victoria, was certainly a refuge with the people he loved and an inspiration for his art.

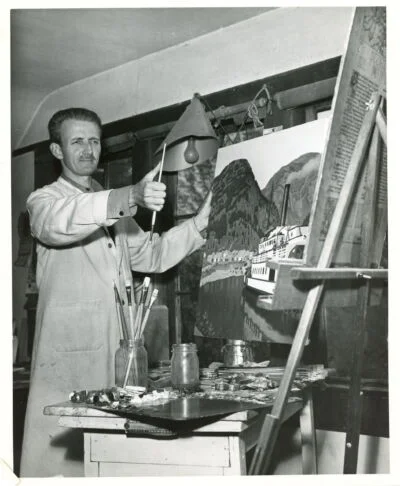

Author Robert Amos, the lucky, able, and compatible choice for being the painter’s biographer, has worked with the Estate of E.J. Hughes to produce four books about Hughes, featuring his art of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, his war years, and his boats. This new fifth book focuses on Hughes’ work while living for 21 years (1951-1972) in a home on the slope of Mt. Baldy and the eastern shore overlooking the lake’s Strathcona Cove. Hughes’ love of nature and the communities of the island shine as a record of twentieth century settlers in this lushly illustrated book.

Growing up in Nanaimo and Vancouver, “Eddie” Hughes experienced the typical difficulties of the 20th century – his father strived to make a living as a musician (trombonist), but also had to take other work. The Depression hit just as Hughes desired to go to the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Art. Through uncles, who provided a North Vancouver home (just as Hughes’ parents moved to Princeton) as well as financial support, he was able to attend the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Art from 1929-1933, working with Group of Seven artists Lawren Harris and Frederick Varley, though also influential was the Principal Charles H. Scott. Making a living as an artist was tough in the Depression years. He stayed for a post-graduate year, tried his hand at teaching, turned his focus to printmaking to make a living, and exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1935 and 1936. Hughes also formed a partnership with Paul Goranson and Orville Fisher called the Western Brotherhood which produced murals, for the Malaspina Hotel in Nanaimo, the First United Church in North Vancouver, the W.K. Oriental Gardens, and most notably the 1939 Golden Gate Exposition in San Francisco.

He met his future wife, Rosabell Fern Irvine Smith (known as Fern and later often referred to as Mrs. Hughes), while sketching deciduous trees at Second Beach in Stanley Park, Vancouver. She was walking her dog while on a break from being a companion for her grandmother who lived on nearby Robson Street. Her family was from Regina, and she impressed him with the considerate way that she asked if she could look at his work. With her politeness, seriousness, and patience, Fern became the perfect partner for Ed, happy to be a homemaker without career ambition and supportive of his art work in a home studio.

In order to marry, however, Hughes needed to find more dependable work. Even with summers working on fish boats in Rivers Inlet and his art work, he was cash-strapped. He remembered his teenage experiences with the Cadets, and so, in September, 1939 (just before war was declared), he joined the army with the Royal Canadian Artillery. He and Fern were then able to marry in Vancouver with Ed’s brother Gary as best man and his sister Zoe as bridesmaid.

Hughes was posted to England and from 1942-1946 Hughes was an official Second World War artist. Though he never was sent to the European front to witness and record the violence and hardship of the war, he was exposed first-hand to the grimness and tragedies that his comrades in the military and the civilians in England suffered. His posting to Kiska, Alaska in November, 1943, in the aftermath of brutal fighting, was just before extreme winter weather, which was extraordinarily challenging for anyone, let alone an artist who was expected to survive the freezing cold and wind while creating sketches, often without shelter. By 1944, Hughes was posted to the Canadian War Records, Ottawa, re-united with Fern, worked as an administrative officer, reaching the rank of Captain, and completed a wealth of oil paintings based on his sketches.

Meanwhile on a personal level, he and Fern had their own severe sadnesses. First, they were separated often by Hughes postings. Then the couple lost three children – a stillborn son Edward (due to a burst appendix) in 1941, a premature daughter Elizabeth who only lived a few weeks (1942), and a healthy son, McLean, who did not survive his first year due to meningitis (1946). Heartbreaking. Beyond words.

How to carry on? Only now are we recognizing the full effects of post-traumatic stress syndrome and the anxieties created by war and difficult work and home situations. Upon returning to civilian life in 1946, Hughes faced the challenges of making a living, coping with disturbing war memories, and the grief of lost children. Both Fern and Ed had supportive parents and siblings, whom they valued. The couple moved to Victoria to live in an upstairs apartment in his parents’ home (Edward and Kay Hughes) in James Bay where Hughes was able to use one room as a studio. Through the recommendation of Lawren Harris from his art school years, Hughes was fortunate in 1947 to be the first recipient of the Emily Carr Scholarship which made it possible for him to go on sketching trips on Vancouver Island. Then again in 1948 he received the same scholarship and had the funds to go on the Princess Adelaide up the coast to Prince Rupert and to sketch locally. He sent paintings to the Canadian Group of Painters in Toronto and Montreal and was nominated by A.Y. Jackson for membership in the group. There were positive reviews of his work at the B.C. Artists Exhibition in Vancouver, and the Vancouver Art Gallery purchased his Farm Near Courtenay.

In 1950, due to the recommendation of Lawren Harris, the National Gallery of Canada purchased Tugboats, Ladysmith Harbour, making Hughes one of the few living B.C. artists in the national collection.

The couple had been able to buy their own home in Victoria with a room for Hughes’ studio as well as rooms to let for another income stream. However, the work entailed to maintain the home and deal with tenants took valuable time away from painting; in addition, they found the tenants could be unruly and slow to pay rent. The quiet and time Hughes needed both personally and professionally was not there. They moved to several other homes on their own, but as Hughes wrote to his sister from their Vining Street home, he could not work with the neighbours’ carpentry banging, car exhaust fumes, children shouting and repeatedly kicking balls against the fence. Hence, the urgent need to move to the countryside.

In 1951, Hughes spotted two listings side by side – for a house and two cottages with 50 feet of waterfront on the east side of Shawnigan Lake, a community linked by the railroad and a newly paved road. When he and Fern went to view it, the quiet was paramount. This cozy house had an upstairs room for a studio with a stunning view to the water. It was easy not to take in that the only water was an outside faucet and that the heating was simply a wood stove. The surrounding forest made it private and away from neighbours, though this asset would create work when leaves needed to be removed from gutters and branches cut back from the building. With help from his parents, Hughes purchased the place, and in time they came to live next door. Finally, he had the quiet (though not always the time) to concentrate on his painting.

He still had money worries, but 1951 was a most fortunate year. After seeing some of Hughes’ paintings of boats on loan to the University of British Columbia, art dealer Max Stern of the Dominion Gallery in Montreal, finally tracked down Hughes and bought all 14 oil paintings in the studio as well as 32 pencil sketches and some prints; he also wrote a contract to buy everything that Hughes produced in the future. Thus started a long association with the gallery but equally important a mutually respectful friendship with its encouraging and sustaining owner Max Stern. Hughes has been called a recluse because he needed silence and alone time. Yet he also needed to discuss art and his work, and Max Stern proved an invaluable critic and positive support. As a dealer, he knew what was appealing to potential buyers, and he was an advocate that ensured Hughes work was purchased by major public institutions as well. He gave Hughes his honest advice which the artist seemed to accept graciously; for instance, Stern suggested that water be included, when possible, in a painting and suggested a distant horizon, not a closed-in scene. Their decades long correspondence reveals the deep relationship they maintained until Stern’s death in 1987. It was remarkable considering that the men met in person on only four occasions. The Dominion Gallery was Hughes’ sole dealer, and he continued with them under Michael Moreault until the gallery closed in 2000.

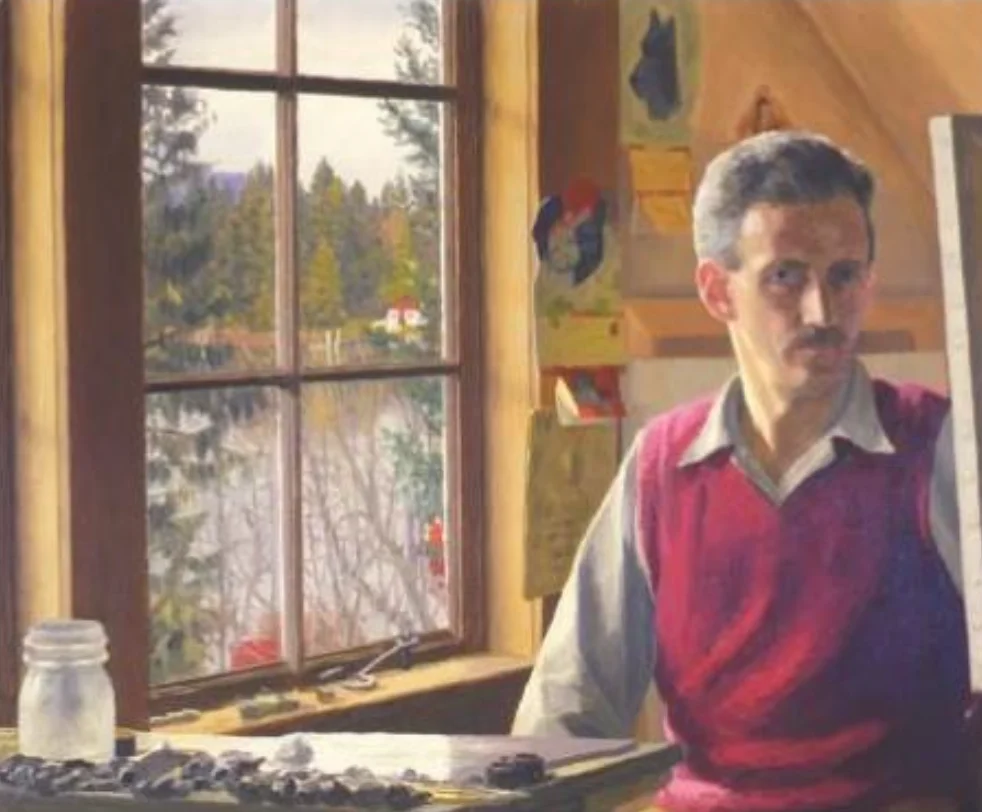

With financial worries curtailed, the couple settled into a peaceful life at the lake, and Hughes produced some of his most iconic work while resident at the lake. His only self-portrait painting was completed in his studio looking through the woods to the lake.

It was at this time in his life when he could afford to purchase his own boat, which made life much easier since they did not own a car until 1959 and needed to walk to Shawnigan Lake village to purchase supplies and go to the post office. Even when they purchased the home, Fern had difficulty walking up hill to their home, and later she would be diagnosed with muscular dystrophy, a progressive weakness and loss of muscle mass. Thus in 1955 they purchased Burma, a small inboard motor boat; then three years later Hughes bought a 15-foot cedarstrip Peterborough runabout with a 1954 Johnson Seahorse with a 25-horsepower outboard motor. He apparently loved cruising around the lake, investigating its many coves, vegetation, changing water and light. A favourite must have been Rose Island, seen in an oil produced from earlier pencil sketches with clear colour annotations, a typical process for Hughes’ creations.

Though known for his landscapes with wider views, he often mentioned the importance of nature, it is not surprising that he looked at the smaller elements, especially the abundant native wildflowers of the island as seen in the vase with Nootka Wild Roses and the Aquilegia (Columbine) pencil study. A study of a fern frond is a touching reminder of the close, compatible and harmonious relationship with his wife. Indeed, his large paintings often had wildflowers and grasses carefully depicted in the foreground as seen in Beach at Savary Island, which was his second painting purchased by the National Gallery of Canada. Plant identification and preservation was not on his radar.

Though certainly an astute connoisseur of natural elements, Hughes also had what seems to be a fascination with the modern industrial and vehicular world of his times. His stunning painting of Mt. Baldy behind his home and beside the neighbouring Strathcona Lodge School for Girls (whom in contrast to neighbours in Victoria, he found “cute” waving at him with slender arms when sitting on a float for a drawing class) is depicted from his boat. In his notations, he details why there were two lines on the bow of the boat – one an anchor line and the other the painter for tying up the boat (just in case you didn’t know). In his painting West Arm Shawnigan Lake, the luminous water in a magical setting is seen over the meticulously depicted outboard engine of his boat.

Many of his works include elements that a purely nature-loving artist might have omitted or downplayed – storage tanks, hoses, oil pipes, cranes, log dumps, barges with sawdust, smoke stacks, warehouses with lumber stacks, dilapidated pilings, old wharves, car line-ups. After all, he had been a war artist, whose job was to depict the tanks, trucks, jeeps, guns, and other artillery of the military. Though his paintings of the mess halls were charming, he was aware of the “real” business of war.

He was definitely a man of the fossil fuel world! In fact, the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey commissioned him in 1953 to provide illustrations for their house magazine, The Lamp. Stern, ever savvy to a lucrative deal, advised Hughes to accept the assignment and to charge them the reproduction rights at $400-$500 for each painting; Stern would then buy the paintings and sketches from Hughes. As a result, Hughes traveled on the company Imperial Nanaimo, which carried gasoline, stove oil, and other petroleum products to coastal communities from Burnaby near Vancouver to Haida Gwaii (then called the Queen Charlotte Islands). He was prone to sea- sickness, and certainly the boat was less private and more rushed than he liked, but he made $2,000 from the reproduction rights (for five paintings) and more from the sale of his paintings. Meanwhile, his sketches provided abundant material for future works. Though there was ample evidence from scientists that fossil fuels and other industries were affecting the environment, Hughes, like so many fellow citizens (raise your hand!) was not fully aware nor advocating change.

Another source of extra income were his commissions with the Canadian Pacific Railroad.

In 1954 he painted a mural (“Eutsuk Lake”) for the Tweedsmuir Park car on the “Canadian Train” service and then in 1958, he completed a mural (“View from Qualicum Beach”) for the Royal York Hotel in Toronto. In the same year he created the painting for the cover of the B.C. Telephone Directory.

With the sponsors Hughes was able to make sketching trips to the interior of B.C. (thanks to Mrs. Doreen Norton) and across Canada to Calgary, Regina, Toronto, Montreal (with financial support from Max Stern). He was also awarded his first (of three) Canada Council fellowships to sketch around British Columbia. The wealth of paintings including “South Thompson Valley at Pritchard, B.C.”

In 1959, Hughes now had the income to buy his first car, a boon for accessing sketching locales without relying on public transportation. It was easier to carry his art materials, and there was shelter during inclement weather. The car also made it possible for Fern, whose mobility continued to decline, to enjoy accompanying him. They bought a second-hand 1952 Pontiac Strato Chief, a turquoise two-door model. Nearby sites were favourites, including the Koksilah River, Cowichan Bay, Crofton, Salt Spring Island.

Hughes also made his only trip to the west coast, producing refreshing views of the Pacific coast as well as towards the Rockies, where rain and cold conditions made sketching difficult.

In 1961, Hughes was featured (along with artists Jack Shadbolt, B.C. Binning, Takao Tanabe, and Gordon Smith) in the CBC’s The Seven Lively Arts and was expressed how he painted Nature matter-of-factly, revealing that it showed his appreciation of what has been created, rather than creating things himself. He found Nature to be wonderful and his painting was a form of worship. In 1968, he became an Academician of the Royal Canadian Academy of the Arts.

By the early 1970s, Fern was wheelchair bound and also suffered from diabetes and visual impairment. Already so much of his time was being used to care for the house and yard; now he had increased work and worry with his wife’s condition. In 1972, they moved to a one-story house in Cobble Hill, which had an extra bedroom for his studio. In addition to easing Fern’s mobility difficulties, there was also an acre of land so Hughes hoped that they would escape the increasing noise and busyness of Shawnigan Lake (power boats, water skiing, more tourists). Though this home was practical, Hughes mourned that it lacked the dignity of their Shawnigan Lake home. By 1973 Fern had passed away, and in his grief, he searched for another home, moving several times to Duncan, Ladysmith, and eventually to a home on Heather Street in Duncan.

However, his Shawnigan Lake connection remained through the stalwart and kind support of a former neighbour, Pat Salmon, who had been a slide librarian and lecturer at the University of Victoria’s History in Art Department. She became his secretary, chauffeur, “crowd controller” (to preserve his privacy), and aimed to write his biography, organizing his papers and recording his memories. Hughes had continued his love of cars, purchasing an Oldsmobile, then a Mercury Grand Marquis, and finally in 1989 he proudly owned a Jaguar Vaden Pass, impressed with its power (and seemingly unconcerned about emissions), though his companion Pat Salmon was often the driver in later years. She ensured that he could reach sketching places, go to his favourite restaurant (the Dog House in Duncan), and shepherded him though increasing exhibitions (Surrey Art Gallery, Nanaimo Art Gallery, Kamloops Art Gallery, the University of Victoria, Vancouver Art Gallery) and recognition – Honourary Diploma from the Emily Carr College of Art and Design (1985), Honourary Doctorates from the University of Victoria (1995), the Emily Carr College of Art and Design (1997), and Malaspina University College (2000), as well as the Order of Canada (2001) and the Order of British Columbia (2005). With the exception of the opening of his exhibition at the Auld Kirk in Shawnigan Lake (1998), Hughes did not attend openings and maintained his quiet, humble presence. After E.J. Hughes died in 2007, Pat Salmon worked with the Estate of E.J. Hughes and eventually, realizing that she was getting older, she arranged for the biographical work to be passed to Robert Amos, who had consistently been positive and supportive of Hughes as an art critic for the Victoria Times-Colonist newspaper. One of Hughes last paintings of the lake was from the patio of Pat and Martin Salmon’s new home.

To the importance of life at the lake imagined at the beginning of this review can be added healing. The writings about Hughes do not reveal friendship or consistent contact with First Nations people, though there are a number of Indigenous groups on Vancouver Island, especially in the Shawinigan Lake – Cowichan areas, who have a rich culture very attuned to the land and sea. However, they have had their own tragedies, traumas, and healing customs which are different from Hughes’ background. Nonetheless, the landscapes – plants, water, earth, and sky – have proved valuable to us all as humans, no matter our perspectives, thanks to the healing qualities of life at the lake.

*

Christina Johnson-Dean graduated from the University of California, Berkeley (B.A. in History with Art minor) and then trained as a teacher. After three years teaching in public schools, she took her retirement money and traveled around the world, teaching in Thailand and New Zealand, before settling in Victoria. She completed a M.A. in History in Art and served as a teaching assistant as well as creating local art history courses for Continuing Education. Since 1987 she has been teaching in the Greater Victoria School District. Her publications include The Crease Family: A Record of Settlement and Service in British Columbia (1981), “B.C. Women Artists 1885-1920” in British Columbia Women Artists (Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1985) and three titles for Mother Tongue Publishing’s Unheralded Artists of B.C. series: The Life and Art of Ina D.D. Uhthoff (2012), The Life and Art of Edythe Hembroff-Scheicher (2013), and The Life and Art of Mary Filer (2016). In addition, she contributed to Love of the Salish Sea Islands with an article about Gambier Island (2019). [Editor’s Note: Christina Johnson-Dean has recently reviewed the work of Kathryn Bridge as it pertains to artist Sophie Pemberton.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “A studio by the lake”

This is such a fascinating exploration of the themes in Amos’s work. The depth of analysis and the connection to broader societal narratives are truly thought-provoking. I especially appreciated the insights into how the personal intersects with the universal in Amos’s storytelling. Great read!

https://crestpainting.ca/