A ‘visually beautiful book’

Kimiko Murakami: a Japanese Canadian Pioneer

by Haley Healey, illustrated by Kimiko Fraser

Victoria: Heritage House, 2023

$12.95 / 9781772034677

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

Haley Healey has written about Kimiko Murakami before, in her book for adults On their Own Terms: True Stories of Trailblazing Women of Vancouver Island. Now she has retold the story, supposedly for children ages 4-8.

Kimiko Okano was born in Steveston and from the age of five raised on Salt Spring Island. There were several visits to Japan. During one she was introduced to Katsuyori Murakami, who became her husband. They and their five children farmed on Salt Spring until the Second World War and their displacement, along with other Japanese Canadians, to the mainland, the British Columbia interior, and Alberta. After the war they returned to the island to find everything they had owned and worked on destroyed or removed and faced the necessity of rebuilding their lives on the land they had thought of as home. They rebuilt, flourished and became highly respected members of the community, dedicated to the preservation of their Japanese-Canadian heritage.

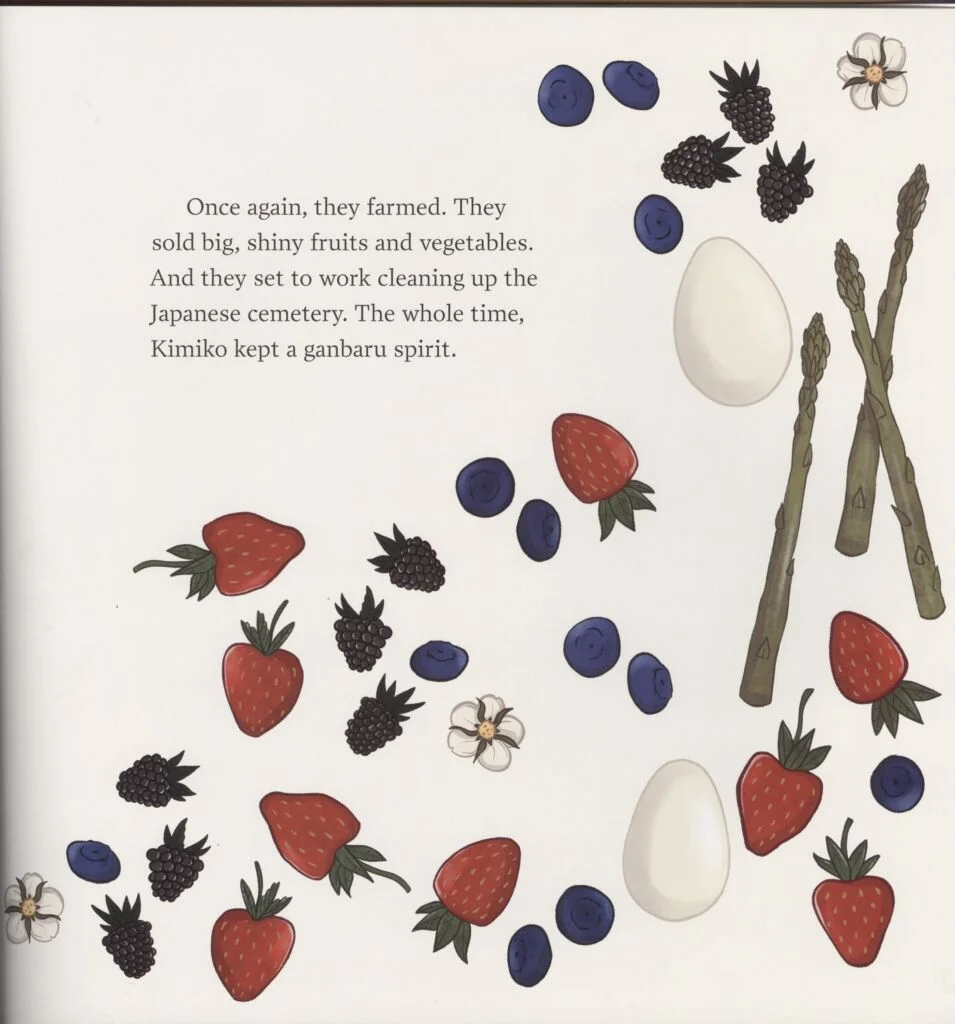

Our children need to know this story, so they understand and do not repeat it. They will be drawn into this visually beautiful book by Kimiko Fraser’s bright, boldly outlined illustrations: the pre-war family and farms, the sad processing lineup at the beginning of the internment, the bleak fields and shacks of the camps, the jar for saving pennies for the postwar home, the return to the island, preparing and planting, and the “big, shiny fruits and vegetables”.

Unfortunately, the text is problematic. When Veronica Strong-Boag wrote about Haley’s book 50 Trailblazing Women of British Columbia the editor gave the review the title “Missed Opportunities.” The same title could serve for this review. Haley might have written a book which engaged and enlightened young children, but I don’t think she has done so. Kimiko is a child for only one page, and by page three she is a wife and mother. We have her children’s names but that is all; we don’t follow their point of view. The first sentence “Kimiko was born in a coastal village outside of Vancouver” is a missed opportunity to identify Steveston, the heritage village which many B.C. children will recognise. The second sentence “When she was five years old, she and her family moved to nearby Salt Spring Island,” misses the opportunity to experience the child’s move by boat to an island more than 70 km distant, not particularly “nearby.” Haley does not mention the journey to Japan while Kimiko was still a child, or her parents’ return to Canada with a new baby, leaving her and her sister with their grandparents in Japan, a decision which, according to the family narrative in the Salt Spring Archives, “upset Kimiko for the rest of her life” – another opportunity for the child reader to empathize, and maybe connect with the later wartime displacement.

Most puzzling is the author’s decision not to make more of the wartime context of the internment. She writes of “new and unfair rules for Japanese Canadians” but does not mention, until the “historical timeline” at the end of the book, that Canada was at war with Japan, or explain the geography of the Pacific. She implies that the only reason for the rules was racism. The rules were indeed unfair, cruel, and undisputedly racist. They could have provided another opportunity: to show in a Canadian setting how the fear and horror of war affect innocent people and too often bring out the worst in all of us, as individuals or as nations.

Haley seems uncertain how to talk to children, and sometimes the text reads as if she were lecturing from a blackboard. Instead of naming things as part of sentences within the narrative, she tells us that she is naming things [my italics]: “a ship called the Princess Mary”, “a place called Hastings Park”, areas made for animals, called barns”, “other places called internment camps.” Her efforts to simplify lead to misleading and even contradictory statements. For instance, she tells the readers “Years later the war ended” – but it was only three to four years. Again, she writes: “Some people treated Kimiko and her family badly for no reason,” but the next sentence goes ahead and offers a reason: the treatment was “because of the colour of their skin or where they are from” and “it is called racism.” I am not sure what message she means to convey by telling her young readers that Kimiko’s family sold their produce “to fancy places like the Empress Hotel in Victoria.”

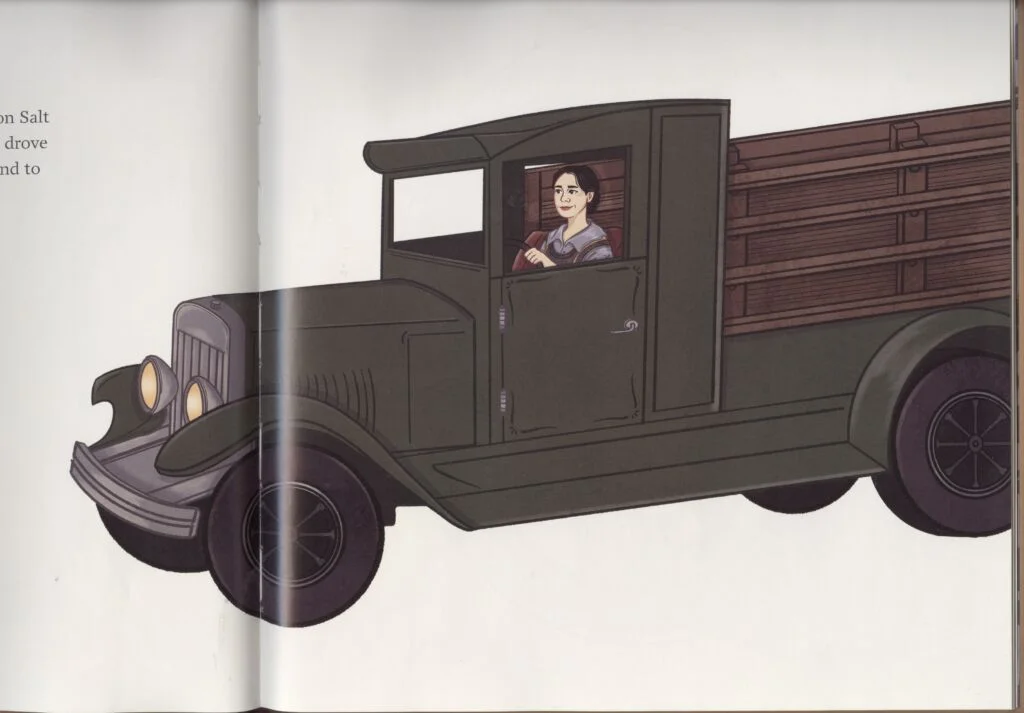

The family is already displaced when Haley introduces the Japanese concept of “ganbaru” which she defines as “to push on through hard times and never give up.” This thread ties the story together, and could have begun during Kimiko’s childhood, in the years missing between the first and second pages. As the blurbs suggest, she was indomitable, persevering, brave, strong, and an embodiment of the ganbaru sprit as well as a role model. I am not sure she was a “trailblazer” or a “pioneer”, despite the claims on the title page. She was not alone; she and her husband seem to have been a forceful team. Does the distinction of being “one of the first women on Salt Spring Island to learn how to drive” qualify her as a pioneer? However, I do like the picture of her at the wheel of the large 1930s truck on her way to buy chicken feed or sell eggs.

In fact, I like all of Kimiko Fraser’s pictures and the engaging design by Setareh Ashrafologhalai. A reader, whether child or adult or – most likely – one reading to the other, could make up a story to go along with the illustrations. It might even be the story Haley Healey meant to tell.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve was born in Fiji, grew up in Quebec, and has lived most of her life in British Columbia. Her most recent publication, in Dorchester Review #25 (Spring/ Summer 2023) revisits the history of pre-colonial Fiji in the writings of her paternal grandmother Richenda Parham. Editor’s note: Phyllis Reeve has recently reviewed books by Doug Harrison, Dave and Rosemary Neads, Robert G. Allan, Mother Tongue Publishing, Lara Campbell, Michael Dawson, & Catherine Gidney, and Donald Lawrence, Josephine Mills, & Emily Dundas Oke, for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster