‘British Columbia’s first professional artist’

Sophie Pemberton: Life and Work

by Kathryn Bridge

Online: Art Canada Institute, 2023

Unexpected: The Life and Art of Sophie Pemberton

curated by Kathryn Bridge

Exhibition, Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, September 23, 2023- January 21, 2024

Reviewed by Christina Johnson-Dean

*

Imagine being born and growing up in a peaceful land beside calm seas protected from open ocean, with stunning alpine peaks in the distance. It is a countryside filled with extensive oak and fir woodlands, interspersed with meadows of edible and medicinal plants, many successfully cultivated for ages, as well as abundant game and fish. Furthermore, your family and community are prosperous, educated, and often supportive of you, so that you have the economic means and encouragement to carry out your dreams and ambitions.

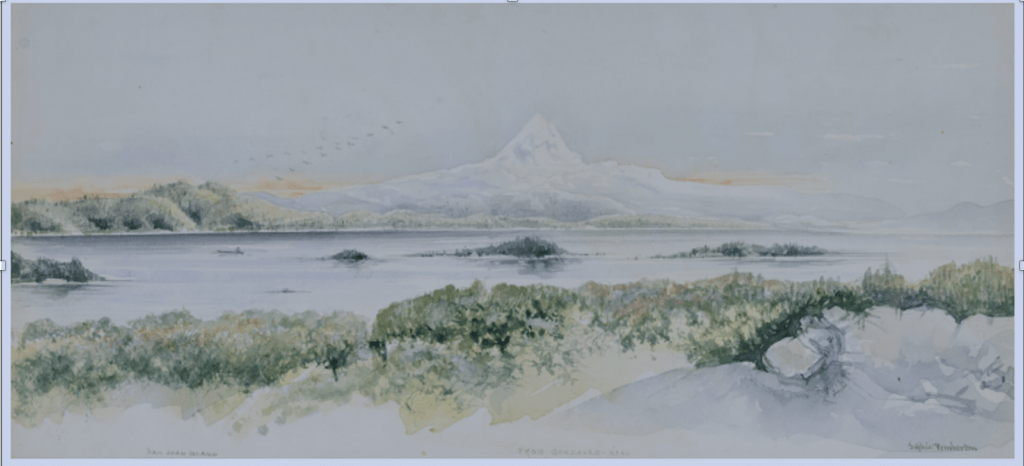

This was the idyllic world into which Sophie Theresa Pemberton was born in 1869 as the third child of Joseph Despard Pemberton (1821-1893) and his English wife Theresa Jane (nee Grautoff) (1843-1916) at Farm Cottage, Victoria, then a colony in the British Empire. But as the extraordinarily well-researched book and beautiful, large, and detailed exhibition portray, life typically has its ups and downs, and the clear trajectory expected of an accomplished, determined, and privileged artist is tangled with unexpected illnesses, injury, and loss as well as restrictive viewpoints, particularly regarding her gender and her Canadian homeland far from dominating art centres abroad. However, her story is more important than thoroughly showing B.C.’s first professional artist for her grace and grit in successfully navigating complicated decades of change. For this viewer, it also highlights the value of our natural world, one that continually sustained her and is currently pertinent to the challenges we now face with the environment as well as reconciliation with our native peoples. Contrast her painting as a 13-year-old, View from Gonzales (1882), taking in the expanse of her family’s land and across the straits to distant Mt. Baker, with the same view of a more mature artist and woman of 39 years in 1908. What had happened?

By 1908, Sophie had studied art formally under Arthur Cope and at the Clapham School in London, impressing both English critics and provincial art lovers when she sat the 1893 government-regulated exams of the South Kensington Schools with outstanding results: First Class designations in each of “Drawing from the Antique”, “Drawing from the Life Subject”, and “Painting from Still-Life.” Sophie established herself as an artist at #3 Stanley Studios, Park Walk, Chelsea, with the company of other professionally motivated women artists, clear allies of the growing feminist movement. She participated in many exhibitions, including her first break in 1897, when the Royal Academy accepted Daffodils, a life-size, full-length portrait, and received high praise when it was hung “on the line” at eye level in coveted Gallery 1. The reviews were positive; however, the prejudice that women faced was revealed in a review that noted it was a conscientious work but “scarcely worthy in subject of the labour and talent bestowed upon it.” She was again accepted at the Royal Academy in 1898 with Little Boy Blue, which was noted for using the more modern “French style” of Impressionism, again with glowing reviews. She was attuned to the latest in art circles, accomplished with portraits, capturing the essence of the people she painted. And always the natural world wove its way through her work.

Sophie had also proved herself in France, attending the renowned Academie Julian, winning the Prix Julian in 1899 (a competition open to men and women though judges knew neither name nor gender) and the next year she was a co-winner of the Julian Smith Foundation Prize of Chicago.

She maintained her London studio and sent her works to the Women’s International Exhibition in London and the Canadian section of the Exposition Universelle in Paris and to the 1900 Royal Academy exhibition.

When Sophie returned to Victoria in 1900, she completed the oil canvas Interested (later entitled Un Livre Ouvert) for the Royal Academy of Arts in 1901 (and then sent it to the Paris Salon in 1903). It showed local residents Ellie Paddon and Ethel Vantreight reading a book by a fireplace, a scene that could have easily been at a country estate in England. However, she also continued her love of being outdoors to work, some of it probably a result of her mother’s discomfort with having models in the house. When traveling with her mother and sisters in northern France, Sophie would escape on her bicycle “Susannah” with portable easel, stool, and art kit to paint outdoors. In 1902, she completed Spring and John O’Dreams, both showing thoughtful people, relaxing on Pemberton lands. They were shipped to her London studio when she returned in 1902 and then to various exhibitions. The rich Indigenous culture of the province, especially in wood sculpture and painted designs, which fascinated other artists such as Emily Carr, did not feature in Sophie’s work, though London audiences had long been intrigued by the native art of North American and other colonial areas. If her mother disapproved of models being in the studio, it seems that the inclusion of Indigenous culture in Sophie’s world would have likewise been unacceptable.

These successes had been made possible by her family’s financial support. In 1851, Sophie’s father, a native of Ireland, trained in engineering and surveying, was engaged by the Hudson’s Bay Company as Surveyor for Vancouver’s Island. By the time Sophie was born in 1869, Joseph Pemberton had surveyed and set the sales policies for the urban and rural areas of Victoria, the land to the north on Vancouver Island, as well as town sites in the late 1850s when the new Colony of British Columbia was created. Politically, he served as a member of the legislative assembly of the colony and then was a member of the legislative council and executive council of Vancouver Island until his retirement in 1868, and finally became a Justice of the Peace for B.C. as a province. He was a wealthy and well-respected gentleman, who owned large tracts of land in what is now Fairfield and Oak Bay. By 1887, he and his eldest son Frederick Bernard Pemberton had formed Pemberton and Son, Surveyors, Civil Engineers and Financial Agents, a business which was the beginning of a real estate and investment company, still operating today. The economic comfort of Sophie’s life was based on land, acquired from the local Lekwungen-speaking people through British treaties, legalities, and sales policies, which in our current times of recognizing Indigenous world views and rights, is seen as unjust and discriminatory.

When her father died in 1893, Sophie met a serious physical challenge – partial paralysis of her lower limbs and general weakness. With a return to Victoria and rest, including a stay in a California sanitorium, she resumed her life abroad and her intense pursuit of life as a professional artist. She was able to do so because in his estate her father left $1,000 per annum to each of his three daughters upon reaching the age of twenty-one to advance themselves in art, literature, or music, or for the purpose of foreign travel. Since colonial days, the Pembertons were respected as the gentry, who brought civilized customs, political, economic, and cultural, to the colony and then province; the lens was focused on what was in vogue in England and the continent. Their large home, Gonzales, was situated on an expansive tract of land (1200 acres) with woods and meadows and featured a tower where Sophie had a painting studio with skylights and windows facing the sea and mountains.

For female settlers of this class, sketching and painting were acceptable activities. Sophie enjoyed the outdoors, and there would have been the camaraderie of others on sketching picnics. Throughout most of her life Sophie worked en plein air to produce watercolour landscape paintings as well as the basis for many of her oil paintings.

An enduring theme were the wildflowers, which were featured in her 1895 Wildflowers of British Columbia. She gave copies to her older siblings – brother Fred and sister Ada (who both loved gardening). Each plant in Sophie’s booklet of flowers was carefully painted and attractively paired with a poem or passage from English literary sources.

There was no mention of the value of the medicinal or edible attributes of these plants, which the local Lekwungen-speaking people had cultivated for centuries, valuing the acorns of the oak forests and the bulbs from the fields of camas. Sophie sketched and then luminously painted the natural world as if it was in England or France.

Though her family provided strong social and financial support, there were obligations and expectations, difficult to overcome, especially as a feminist. Thus in 1905 she married Canon Arthur Beanlands, a widower with four children who presented as a well-read art lover who would be supportive of her work as an artist. Sophie initially had her own studio in the rectory, but too, soon became space where her husband and step-children, including the youngest, Paul, to whom she was most attached, also spent time. Undeterred she completed portrait commissions, including Lady Sarah Crease, who along with her daughters (especially Josephine) were accomplished watercolourists, active in the local arts community. Sophie and Emily Carr supported the founding of the British Columbia Society of Fine Arts in Vancouver. By 1907 she had been successful in her application to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

Probably the most telling painting of the difference between her world view and current concerns was in the painting A Prosperous Settler, a cheerful rendering of another Mt. Baker view with a flourishing broom plant in the foreground, overtaking the native camas flowers. From our current perspective (when countless people are removing broom as well as other invasive plants from abroad such as ivy and gorse), the painting clearly shows the contrast – the colonial, settler’s love of the imported plant without apparent awareness of its destructive impact on the native environment. It’s our current struggle – economic prosperity and the many pleasures and ambitions it can buy juxtaposed with awareness and actions for a strong and thriving environment.

At this time, Sophie sent no paintings abroad. Her painting Penumbra, which was painted over Autumn (the match to Spring) shows a young woman deep into thought and emotion in a wooded area, caught as the title indicates, between light and shade. Around that time Sophie’s illness had returned and she would endure two surgeries and lengthy hospital stays. The challenges of married home life and illness would certainly have been draining. It was also the time when she painted Time and Eternity, the contrast to her teenage View from Gonzales and A Prosperous Settler. Dominant is the remnant of a dead oak tree, though less obvious is a sapling that has grown from one of its acorns. The book discusses this key work as a “think piece”, with the volcano as eternity and the old oak tree next to the young tree as regeneration. Style-wise the painting is described as Post-Impressionistic, expressing her mood and personal feelings. Sophie was ever maturing and broadening as an artist, capable of being attune to trends abroad.

By 1909, Sophie had returned to England, successfully mounting an exhibition Sketches of Victoria at the Dore Gallery on Bond Street. She again exhibited extensively, including at the Royal Academy, the Royal Canadian Academy, and the Art Association of Montreal. Her husband joined her, and with money from her family, she was able to purchase Wickhurst Manor near Seven Oaks, Kent. Sophie became the representative for the local branch of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, and by 1914 served on the national council of the Suffrage Service League. She knew well through personal experience how important voting, work, and financial resources were for women.

Art Gallery of Greater Victoria

And then tragedies occurred: deaths in the family – her brother Fred’s sons in the First World War, her mother and her brother Joe (1916), her husband Arthur Beanlands (1917), and her beloved stepson Paul (1919). More critically, about seven months before her husband’s passing, Sophie suffered a head injury with debilitating headaches for three years after a dog cart that she was driving collided with a lorry. What carried her through was the encouragement of a neighbour to paint floral and bird designs on domestic pieces such as tea trays. In 1920, Sophie remarried a widower, Horace Deane-Drummond, who had tea plantations in India and Ceylon, and they went on extensive travels. She resumed her painting, and in 1921 when they visited her family in Victoria, she produced The Driveway of Moulton Combe, the entrance to the home of her younger sister Susie and her husband William Curtis Sampson, situated on the subdivided lands of the old Gonzales estate, near sister Ada’s home Arden in Oak Bay. It shows that despite the dog-cart accident and head injuries, she is still an accomplished painter with full command of light, colour, and movement, a bucolic scene of an English garden, not the increased development in the area. The trees are covered in English ivy, already a lethal invasive plant for native trees. She was probably not aware of the danger, but importantly, she documents what was there visually as well as what was probably common thinking – the ivy was lush, intriguing, and appealing from that painterly perspective.

Art Gallery of Greater Victoria

Throughout her life she depicted her favourite flower – the fawn lily (Erythronium oregonum), which now thrives in Oak Bay’s Native Plant Garden, located on property donated by Ada, part of the land where she and husband Hugo Beaven resided. Sophie’s first formal art training in England began in 1889 at Arthur Cope’s school with a traditional academic programme of anatomy classes and drawing plaster casts from ancient sculptures. Yet the fawn lilies slipped through, making her oil painting of a plaster cast far more personal. The lilies were still there in her twilight years, when her correspondence often included a small sketch of this native lily. She was remembered as delightful, modest and exceptionally gracious with a mind not closed to new movements of the twentieth century. Though firmly comfortable with her outlook then, if she were alive now, would she have been sympathetic to our contemporary concerns of economic equity, preserving green space and native plants as well as increasing our understanding and appreciation of Indigenous cultures?

The book and exhibition include much material in the Biography not included in earlier works, as well as thoughtful sections on Key Works, Significance, and Critical Issues, Style and Technique, and Where to See her works. Sophie Pemberton was bestowed with many advantages, yet she was not exempt from life’s trials– frustration with family and narrow views of her times, sadness, loss of loved ones, disappointments, on-going illness, and severe head injury. Yet she was highly successful – British Columbia’s first professional artist – and her life from birth in a far-flung colony to being a senior citizen here active in the arts demonstrates what determination and resiliency can produce. She was grounded in a deep appreciation of nature and frequently surrounded herself with community and people who gave her support. Her story brings up the questions we all face – what is worth living for, what do we support and perceive, yet what eludes us?

Art Gallery of Greater Victoria

*

Christina Johnson-Dean graduated from the University of California, Berkeley (B.A. in History with Art minor) and then trained as a teacher. After three years teaching in public schools, she took her retirement money and traveled around the world, teaching in Thailand and New Zealand, before settling in Victoria. She completed a M.A. in History in Art and served as a teaching assistant as well as creating local art history courses for Continuing Education. Since 1987 she has been teaching in the Greater Victoria School District. Her publications include The Crease Family: A Record of Settlement and Service in British Columbia (1981), “B.C. Women Artists 1885-1920” in British Columbia Women Artists (Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1985) and three titles for Mother Tongue Publishing’s Unheralded Artists of B.C. series: The Life and Art of Ina D.D. Uhthoff (2012), The Life and Art of Edythe Hembroff-Scheicher (2013), and The Life and Art of Mary Filer (2016). In addition, she contributed to Love of the Salish Sea Islands with an article about Gambier Island (2019).

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “‘British Columbia’s first professional artist’”

What an absolutely meticulous review of someone with great talent and superb technical and aesthetic abilities.

Thanks Kathryn Bridge and Christina Johnson-Dean for bringing Sophie Pemberton to our collective attention so that she too does not “elude us”.

Pemberton was a gem and this exhibition and on-line essay by the Art Institute of Canada go a long way to revive her spirit and work. Thanks so much to them for doing such impressive art critical history.