Revisiting the ‘Last Spike’

Dominion: The Railway and the Rise of Canada

by Stephen R. Bown

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada, 2023

$28.00 / 9780385698726

Reviewed by Daniel Francis

*

Long before it became a reality, the Canadian transcontinental railway was an idea, imagined by business tycoons eager to make a profit and politicians anxious to bring the two ends of the country together and keep the western plains out of American hands. And it remained a potent idea long after it was built. The building of the CPR has been one of the core myths of the country, one of the stories that explain how Canada came about. The nation would have been impossible without the railway, we have told ourselves. By uniting us sea to sea, making possible the settlement of the West and keeping the Americans at bay, it created Canada. The photographs of the driving of the Last Spike have been called the most famous in our history. Those men crowded around the steel rail not only constructed a railway, they built a nation. These were the real Fathers of Confederation. At any rate, that is what our history books have told us.

It is this all-important founding myth that Stephen Bown has chosen to retell in his new book, Dominion: The Railway and the Rise of Canada. He begins in the 1870s where his earlier book, The Company, a history of the Hudson’s Bay Company, left off and he chooses to start out here in British Columbia. The railway was particularly crucial to the Pacific province because it was only with the promise of a rail link to eastern Canada that BC agreed to join the Dominion in 1871. Bown organizes his narrative around prominent characters and dramatic events. In the case of BC, for example, the reader is introduced to, among others, Judge Matthew Begbie, the Overlanders who trekked across the western interior to the Cariboo in 1862, and Alfred Waddington, whose plan to push a road across the Chilcotin Plateau led to conflict with the Indigenous residents. Important as all these people and incidents are in the history of the province, none of them seem to have much to do with the CPR. Indeed, for the first 200 pages Dominion reads more like a general history of western Canada than it does a focussed history of the railway.

That said, Bown is a capable guide through the major events of the 1870s. Not surprisingly, John A. Macdonald, our first prime minister and the architect of the railway, is front and centre. Macdonald’s reputation has suffered the last few years, principally because of his assimilationist policies toward Indigenous people. Bown struggles to come to terms with Macdonald’s flaws — his heavy drinking, for example, his ignorance of Western Canada, his loose interpretation of electoral probity – while admiring his political skills, his sociable personality, and his ambition for the country. In the end, though, Bown’s assessment of Macdonald is disappointingly trite. “Whether Macdonald was a good man or a bad man is open to debate,” he writes, “but he was certainly an interesting one.” Later he concludes: “Was he a monster? No, but he set in motion some monstrous policies…” Give the guy a break, Bown seems to be saying; he was doing the best he could given the values and beliefs of his time.

Photo Vibrant Victoria.

The Canadian Pacific is associated with one of the country’s most notorious political scandals. In 1872, approaching a general election, Macdonald’s Conservative Party winkled a $350,000 contribution from Sir Hugh Allan, a Montreal business tycoon. Once the election was won, Allan and his cronies received the contract to build the transcontinental railway. Unhappily for Macdonald the opposition got wind of the sweetheart deal and brought down his government. Alexander Mackenzie and the Liberal Party took power and assumed direction of the railway project. Mackenzie favoured a different approach to the construction of the line. He wanted the railway to be a publicly-owned utility not a privately-owned corporation getting handouts from the government. Under the new regime, the Department of Public Works would oversee the line. More a tortoise than a hare, Mackenzie felt no urgency about the project. What of the promise to British Columbia that a line would be built in haste? It was “a bargain meant to be broken,” he said.

Bown is unforgiving about the years of fraud and boondoggle that followed. Contracts were awarded to political friends, supplies were sold to the government at inflated prices, jobs went to party hacks and their relatives. All of which resulted in the inevitable cost overruns. “The corruption and incompetence permeated every aspect of the enterprise,” he laments, “as many saw the sloppy management as a trough from which to feed themselves.” Meanwhile, during the 1870s a series of treaties were made with the First Nations encompassing most of the land north of the border with the United States. Bown details these negotiations, the motives behind them, and the failure of the government to live up to their terms. The Indigenous people were bargaining from a position of weakness. As Bown describes with great empathy, the buffalo which had once sustained them had been hunted almost to extinction. They were starving and the government did little to assist them.

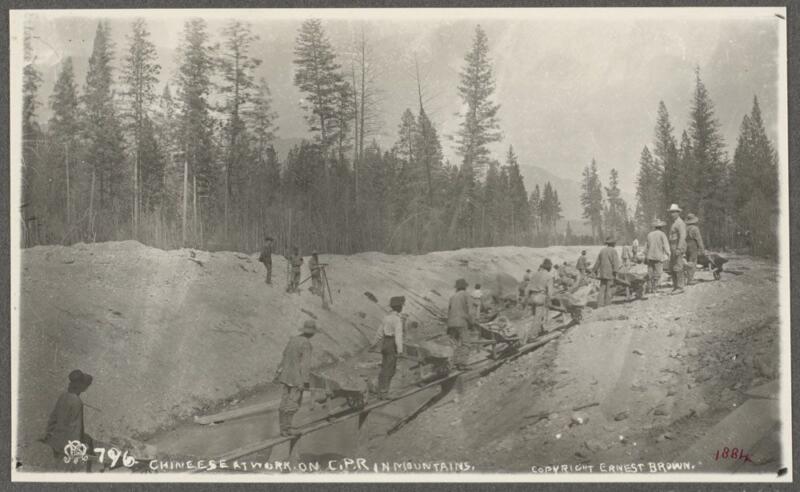

Mackenzie’s government only lasted four years. By 1878, Macdonald was back in power, redeemed by the voters and invigorated by his National Policy, one plank of which was the completion of the railway without delay. The new Canadian Pacific Railway Company was incorporated with huge grants from the government in the form of land and cash, not the last infusion of public largesse it would receive. In return, all restraints were off and construction was hurried across the plains and over the mountains. BC readers will find vivid descriptions of the Chinese crews who pushed the line down the Fraser Canyon under appalling working conditions.

Despite the millions of dollars spent, by the spring of 1885 the railway still was not finished and the company verged on bankruptcy. Without more government help, which was not forthcoming, the project appeared to be doomed. Which is when fate intervened in the form of Louis Riel and the disaffected Métis people in Manitoba and Saskatchewan who recognized him as their leader. The Métis decided to take up arms in defence of their land grievances. They defeated a party of Mounted Police, declared a provisional government and raised the spectre of an all-out frontier insurrection against Ottawa. The presence of the partially completed CPR line allowed Macdonald to rush almost 3,000 soldiers westward from Ontario to defeat the Métis and their First Nations allies. The CPR had saved the day and in return the government saved the CPR by approving the money needed to complete the line. Bown ends his story with the hammering of the Last Spike at Craigellachie, not far from Revelstoke, on November 7, 1885. The first passenger train arrived in Vancouver from Montreal the following summer. “The land would never be the same.”

For Bown, the CPR was both a triumph and a tragedy. “The railway presaged a soaring immigrant population and titanic economic expansion and stymied the US dominance of North America,” he writes. “But it also enabled the often-cruel repression of the land’s original inhabitants and the exploitation of thousands of labourers.” It is this dichotomy that he strives to balance as he tells his story: economic opportunity versus brutal exploitation; national expansion versus colonial dispossession.

Image # C-014464

Given that it is one of the defining myths of Canadian history, the creation of the CPR is a story that has been told by many writers, Pierre Berton not least among them. Readers might well ask why bother telling it again, especially if you really don’t have much new to add to the familiar narrative. By and large, Dominion highlights the usual suspects – Sandford Fleming, Cornelius Van Horne, Major Rogers, Donald Smith, et. al. — and the usual incidents. Nonetheless, it is in the nature of myths that they bear repeating, especially if the story is a good one. A bigger problem with the book is that Bown is a sluggish writer who brings neither originality nor narrative drive to his story. Like the track itself, the way forward is repeatedly blocked by clumps of lifeless prose. He has a fondness not just for fence-sitting (“The question of whether the treaties were good or bad has no answer.” but for stating the obvious as well (“We cannot know the future… The world is always changing, and people respond as best they can.”).

But I am sounding like a sourpuss and I don’t want to end on a negative note. We hear all the time these days about the lack of new popular history and the challenges faced by writers, like Stephen Bown, who want to produce it. At the same time, the story of the CPR is in danger of being neglected by younger generations who do not recognize what a hold the railway once had on the imagination of the country. For that reason, and despite its shortcomings, we should be grateful that Bown has turned his attention to this important story.

Photo Frederick Dally / Library and Archives Canada / C-037864

*

Daniel Francis is the author of thirty books, principally about Canadian and BC history. Becoming Vancouver: A History (2021), was reviewed by Patricia Roy, and Where Mountains Meet The Sea: an Illustrated History of the District of North Vancouver (2016), was reviewed by Trevor Carolan. Daniel Francis previously taken a look at the work of Stephen Bown with his review of The Company: The Rise and Fall of the Hudson’s Bay Empire and has also reviewed books by Martha Black, Lorne Hammond, & Gavin Hanke, Peter Neary & Alan Collier, Ben Bradley, and Mark Leiren-Young. He lives in North Vancouver. Visit his website here.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Revisiting the ‘Last Spike’”

Sandford not Sanford.

Thanks rrr! We’ve made the change.