Authors’ origin stories (x 6)

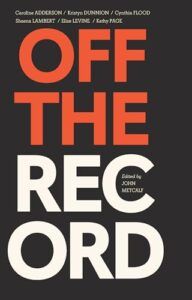

Off the Record

by John Metcalf (editor)

Windsor: Biblioasis, 2023

$26.95 / 9781771965453

Reviewed by Brett Josef Grubisic

*

A writer friend reacted coolly when I slid Off the Record in her direction. “Writers talking about themselves for extended periods of time?” she quipped. “What a novelty. No, thanks.”

Granted, she’s sat through her share of windbags, and at a gallery once we were part of a captive audience as the novelist at the lectern went on about her “praxis” but neglected to read the room.

On the page, though, where final words are set after having been considered and arranged as well as reconsidered and rearranged through who knows how many revisions, I found writers accounts of themselves exceptional, even enthralling. And certainly not the off-gassing of egregious or fatuous navel-gazers.

Carefully wrought, tonally diverse, artful, thoughtful, revelatory, and nothing short of enticing, the essays showcase authors with an assigned goal that they’ve taken seriously and polished to a gleam.

Evidently pondering associations inspired by a core question (“How did you become a writer?”) six well-established Canadian writers—four (Caroline Adderson, Cynthia Flood, Shaena Lambert, Kathy Page) residing on BC’s coast, one (Kristyn Dunnion) in Toronto and another (Elise Levine), a transplanted Torontonian who resides in Baltimore—summon compelling origin stories. Some are funny and others abstract and cerebral; they’re all poignant and chock-full of anecdotes.

(As for the elephant in the room… Anyone conscious of representational politics in the arts can’t miss the book’s limited diversity. While Metcalf makes no claim whatsoever about this collection’s intention to illustrate anything about Canadian writers in general or publishing in Canada, six white women from urban areas in just two provinces is, well, a choice. The absence of a Prairie writer, one from Atlantic Canada, or from anyone north of the 49th parallel doesn’t diminish the excellence of the essays included, but it did catch my notice. Ditto for the overall ethnic homogeneity. From Adderson to Page, Metcalf’s European surname selection skews Anglo, heavily so. For the book, it’s a missed opportunity. Reading, I was reminded of Katherena Vermette’s comment in a new edition of Beatrice Mosionier’s In Search of April Raintree: “The thing is, and this is sad, but in all that reading I did, I never even expected a book to be about someone like me. I never thought Winnipeg and Métis or other Indigenous people at all would ever be in a book, never mind an important one.” A Vermette-to-be in 2023 will discover no one like her when she pores over Off the Record.)

From what I could tell, the writers had worked with editor Metcalf for one or more of their books and, this time around, formed essays around questions he posed to them. While I have no knowledge about whether one contributor communicated with one another about her own essay and her approach to structure, tone, or degree of candour, there’s a fruitful overlap; there are commonalities.

The essayists note a general restless artistic temperament, for one, though not necessarily focussed on words—or focussed at all. In fact, painting, drawing, music, pottery, architecture, and acting appear significant in the formative years of several writers. (Humorously, Dunnion appeared in a production that an unimpressed reviewer panned as having “less depth than a toilet.”)

An early and unconditional love of reading is common too, though the reading materials vary widely—from a dictionary to Nancy Drew.

Flood (What Can You Do) remembers meeting “in fiction one of life’s great pleasures. It’s never faded.” “Why I read so much: the usual,” she confides, “Lonely, out of place in high school, I’d found company in fiction and hid my love of reading except at home.” And she wrote too: “Did I read and reread because I sensed it was good training? Not consciously. I wrote poetry, got excited if any appeared in university publications—but I didn’t see writing as a career. I expected and was expected to marry soonish.”

Levine (Driving Men Mad) recalls being wildly “attracted to the abracadabra of words,” and for Dunnion, books remain “the most potent way to connect to a life lived differently, and to develop empathy, a vital building block for compassion.”

Taken together, the pieces support the notion that writers are necessarily readers. For this collection’s essayists, to write without reading is nonsensical. Writers read—often, widely, and promiscuously. Of course they do.

Mentors appear in all the essays, with at least one playing an ambivalent role—Lambert’s, “polite and distant and slimly encouraging” Peter Carey, once answered her querying letter (“Tell me. Tell me. How far am I from getting this story right?”) with “A Million Miles.” Lambert read further, “Ah—but a million miles can sometimes be crossed in a single step, or several steps.” Adderson recalls working with Metcalf some forty years ago. Apparently renowned for “coveted abuse,” the man replied to her “timid editorial question” with “Caroline, you go ahead and do whatever the fuck you want” before hanging up.

Relatedly, to assorted degrees the essayists note the absolute value of a writing community (for everything from feedback to friendship). Ditto for a social (or professional) network that extends to publishers, editors, agents, and other literary fixtures, not to mention programs that foster such connections. The clear takeaway for any new writer looking for tips is: don’t go at it alone.

Also, interestingly, there’s ample evidence of what could be called apprenticeship, whether it was conscious or not. A gestation period, perhaps.

None of the writers had serious childhood aspirations to be a novelist; none published books until they’d been writing for years, even decades. Often, the authors came to writing from unrelated disciplines, or after separate careers. Stories were worked on—written, revised, set aside and then rewritten—for years. In short, while a literary ‘overnight sensation’ might be a reality, its exceptionalism makes it almost mythic.

Far more than story- or novel-sized strings of grammatical correct sentences, writing takes vision as well as practice. It takes time. Be prepared, a young writer would be wise to discern as being woven into these essays.

Levine’s recollection of a crush on “the abracadabra of words” takes place in the context of a “volatile household” where the “virulence” of her parent’s marriage crowded the very air. And across these essays, the impact of family life cannot be overestimated.

All of the family portraits—characteristically of the ‘warts and all’—are fascinating; each of the writers shares riveting episodes as they make a case for the indisputably pivotal role of growing up at home. Mom, in particular, does a star-turn for these essayists.

In many cases, the writers peering at the wreckage or drama or “confused magic” (that’s Dunnion) of a childhood and hometown display little doubt about a direct correlation between the lived experience and the eventual aesthetic output.

In other words, how they write and what they write about stems from scenes now many decades in the past. For instance, as Levine’s essay attempts “to take stock, to reckon, translate from old stories sourced from confounding gaps and misdirections, from slippery tenses and sprawling, spiralling enigmas,” she discerns “the how and why of writing” for her. All roads lead to Dad (“a short-fused, verbally abusive philanderer”), to Mom’s “corrosive unhappiness,” and little Elise seeking shelter while also trying to make sense of it all.

Likewise, Page (Dear Evelyn) detects in her mother’s positive and negative qualities the forge of her own writing: A “habit of exaggeration” played a role, as did her mother’s continuous encouragement to “imagine and pretend.” “She knew how to make you notice her words, which were rarely bland, but often suggested a drama of some kind,” Page explains. “If one of us was late for a meal, we had vanished, or absconded. It never merely rained—there would be a tempest or a deluge. My bedroom with the curtains closed was like a mausoleum.”

As time passed: “It was not all dressing up in a sun-dappled garden…. My mother was a powerful woman, a vivid, magnetic personality, and also a fighter, not at all inclined to doubt.” Her “rages were seismic and ruled our lives.” Studying the signatures of her own writing, Page notes the horrible battles with her mother left her “with a deep appreciation of the value of conflict, and how riven with contradiction people are.” And: “Another legacy is lifelong openness to to and interest in difficult people, an active fondness for them.”

Of her youth in Edmonton, Adderson (A Russian Sister) recalls her mother as a “forceful presence” and former stylish single woman in glamorous Montreal whose marriage “ended her happiness”: “she became one of Munro’s stymied protagonists, intelligent and witty, held back by societal expectations of women in the fifties, and the fact that she could never have afforded a university education.” In contrast Flood remembers a supportive, happy mother as well as a father’s anger (“in predictable and unpredictable forms”): “I tried to avoid him, often dreaded his presence.”

Lambert (Petra), who grew up in Horseshoe Bay, states directly, “I became a writer because of my mother.” She elaborates, “Other people have influenced me, but she was the luminous icon. Her struggles to write, her mythic journey, as it seemed to me, made writing seem like something that almost hurt.” She also recalls associating books with power: these “wholly absorbing sanctuaries” gave young Lambert “the right … to say what [she] actually thought”: “Nobody said no to my father. We all—every one of us—appeased him…. The memory still has a flare of subversion to it.”

Growing up in a “one-stoplight town” on Lake Erie, Dunnion (Stoop City) depicts a period of “lunatic self-discovery,” where her ordinarily supportive parents expressed their limits via paternal spankings—and analysis: “my mother became convinced my behaviour was evidence of some form of hysteria and diagnosed me with a nervous condition.” A queer girl in a straight town (“Somehow, I sensed that the path peddled by almost everyone I know would suffocate and betray me”), Dunnion eventually sought communities of like-minded souls.

Complex, multifaceted, and capacious, the essays of Off the Record are complemented with short stories. I’m not convinced the story that follows each essay is strictly necessary. After all, the positioning does encourage the biographical fallacy, which is reductive and ultimately pure Freudian folly in the vein of “Does the anxiety in Lambert’s ‘The Wolf Expert’ actually represent the author’s domineering father?”

Folks, it’s known as a fallacy for a reason. Better to appreciate the stories as literary art: beguiling, special, alluring, and—don’t forget—laboured over for countless hours.

*

My Two-Faced Luck, the fifth novel by Salt Spring Islander Brett Josef Grubisic, published in 2021 with Now or Never Publishing, is reviewed here by Geoffrey Morrison. A previous book, Oldness; or, the Last-Ditch Efforts of Marcus O (2018), was reviewed by Dustin Cole. [Editor’s note: Brett Josef Grubisic has reviewed books by Brandon Reid, Beatrice Mosionier, Hazel Jane Plante, Sam Wiebe, Joseph Kakwinokanasum, Chelene Knight, Lyndsie Bourgon, Gurjinder Basran, and Don LePan for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Authors’ origin stories (x 6)”