Poems embrace the natural world

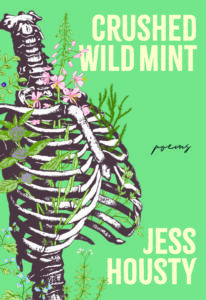

Crushed Wild Mint

by Jess Housty

Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2023

$19.95 / 9780889714502

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

At first glance Jess Housty’s Crushed Wild Mint was not a book that I thought I would want to review: it seemed mystical and religious in ways that I am not. Luckily, I took a second glance and was fascinated.

What strikes one first is the incredibly tactile quality of the writing: “and you settled the words onto my shoulder / as steady as an owl alighting on a low branch.” The imagery is not only accurate and evocative but also surprising. Then, in “Stone,” the ocean at night is conjured up:

like the taut, stretched breast

of a skinned jay,

like the inner surface of a mussel shell

when the meat is stripped away.

While the second image, though striking, is accessible, the first takes the reader into uncharted territory. Do people skin jays? If so, why?

Such images go beyond accurate, trained observation: the poet is in constant conversation with the environment, so that even when not explicitly affirmed, we sense an instinctive continuity with the natural world as an act of total embodiment and self-identification.

Time and again when starting to read a poem I thought it would be ‘poetic’ and ‘precious’; with many other poets it could have been but in, say, “Auricle and Miracle,” the opening lines—“Close your eyes. / Where in your body do you feel / a hummingbird’s flight pattern?—are answered in the next stanza:

For me, it’s the base of my skull radiating through my vertebrae even before the sound trembles against my eardrum

And the summoning of “my other forms, my animal selves” becomes simply straightforward and convincing. When a poem such as “Summer” seems less interesting it is because the premise comes across as more generalized, less anchored in the particular.

Granted, some of the more animistic affirmations appear less self-evident than others. In “Mountains Teach Us” the speakers tells us that “mountains teach us reciprocity,” or, again, “the mountain is tender / and wants us to be well.” In general, as in the title poem and “Dirt Prayer,” in which the poet asks and answers questions—

What does it mean to feel grounded? Imagine tender roots forming, stretching their small hands outward for nourishment How do the parts of you that are in contact with the earth form attachment to place? What do you gain from this attachment?

—the reader has to trust the spiritual wisdom since for the most part concepts such as worship or prayer are sufficiently embodied and made tangible.

These poems, then, require a greater “suspension of disbelief” in its most literal sense than I at least was accustomed to. It was worth the effort. Settler readers may, and indeed I feel should, admire Housty’s holistic approach to the natural world—if only they had done so centuries ago!—but many of us might find it difficult to take over the whole framework of beliefs.

Bella Bella’s Housty adopts a quasi-Biblical, almost prophetic directness and simplicity, as in the refrain, “You said it was so / my love, and it was so.” If, occasionally, the poet sounds too much like a prophet producing instant wisdom, in general the danger of the quasi-heroic and the vatic stance is avoided.

Is it possible to value a poet’s insights yet reject or feel untouched by the belief system they arise from? Surely it is. Otherwise how could I enjoy, and value, Donne’s Holy Sonnets or Gerard Manley Hopkins’ whole oeuvre? How could I be moved by the paintings of Fra Angelico or the music of Hildegard von Bingen? I can appreciate the faith and devotion and submit to their insights in the same way that I could follow Alpine guides: they know the way and I do not.

The one relatively minor problem that I have with Crushed Wild Mint concerns another aspect of language. Although I think I understand Housty’s motive for giving poems titles in Heiltsuk or other First Nations languages, for the non-indigenous readers or even probably for readers from other First Nations, to give poems such titles as “Hjxvbis,” which is not merely unfamiliar but even unpronounceable in English so that one has constantly to refer to the glossary, seems counter-productive. Maybe simply adding the settler name in brackets would be sufficient?

However, this is a small consideration when weighed against the immediacy, tactility, and general imaginative freshness of the poetry that make Crushed Wild Mint a book to cherish.

*

Born in London, England, in 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. The most recent of his many books of poetry is Moorings, reviewed by Trish Bowering. He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978 and was its editor for a decade; he was Series Editor of the Harbinger imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. [Editor’s note: Christopher has reviewed books by Susan Musgrave, Katherine Lawrence Leanne Boschman, Isa Milman, H.C. (Hans) ten Berge, John Barton, John Pass, and Rob Taylor for BCR]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “Poems embrace the natural world”

The “relatively minor problem” this reviewer has is major disrespect. Jess Housty (Cúagilákv) has a reverence for the land, ancestors, traditions and language of the Heiltsuk (Haíɫzaqv) people. The titles of some of her poems may be unfamiliar and yet we can make an attempt to pronounce them. Referring to the glossary adds an English translation to a particular Heiltsuk title and yet each poem vividly depicts the meaning of it. Rather than feel inconvenienced by flipping some pages, readers and reviewers ought to be remembering that it was settlers who forced First Nations people to learn English in a hostile and abusive environment. Surely we can make an attempt to learn the words of languages that were in place long before we or our settler ancestors arrived here.

I think, Mary Ann, Mr. Levenson was not indicating an inconvenience, but merely showing empathy for a myriad of diverse readers. Access to the work, in a society which is diverse, is a reasonable concern. Mr. Levenson also shows empathy for other First Nations, which is also valid, and shows merit. I would suggest seeing the glass as half full. Overall, he provides a glowing review to the work of Jess Housty, a fellow poet. There is reciprocity here, if you are willing to see it.