What is the role of art?

The Compassionate Imagination: How the arts are central to a functioning democracy

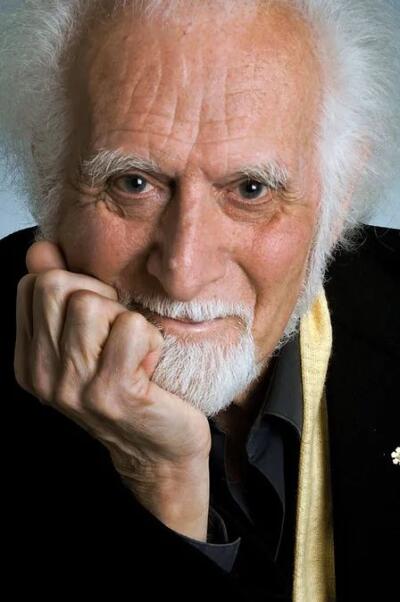

by Max Wyman

Toronto: Cormorant Books, 2023

$19.95 / 9781770866997

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

What is the point–honestly–of putting a lot of energy into discussing the connection between “art” on the one hand and society on the other? Well, Plato seemed to think it mattered–a lot. So did Aristotle–though he disagreed with Plato. And so have an overwhelming number of other philosophers, as well as artists, thinkers, and even, Lord help us, politicians, both enlightened–and, well, the opposite. Think: Stalin. Think: deSantis. And so on.

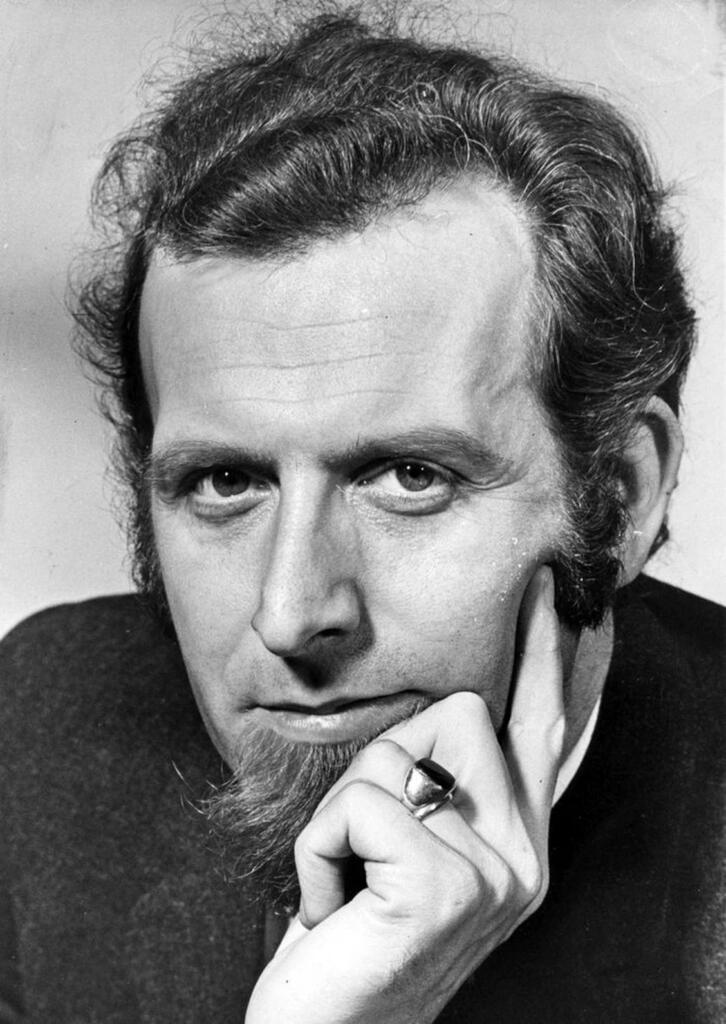

Probably one of the most quoted lines in twentieth century writing is from the final lines of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young man. Burning with quiet zeal, the young artist writes in his diary, “I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” Bring the light of awareness to a whole benighted people through writing? Ambitious? You betcha.

It isn’t just the famous and foreign, though, who care about the connection between art and society. Parallel thoughts are everywhere. Consider a local book about metal workers of the Salish Sea. The role of art in society? One argues for the need to illuminate Indigenous history, another to expose the proliferation of waste products of consumerism, and so on. The Compassionate Imagination, by distinguished critic, arts consultant and writer, Max Wyman, doesn’t just add one man’s point of view to the welter of thought on the subject, but does so from a perspective probably unique to his times and his country– Canada, now.

And what is special about the embattled position of the arts in Canada that this book is so relevant? The answer is complex and varied but the subtitle of the book sounds the central chord: How the arts are central to a functioning democracy.

Building on an earlier book, The Defiant Imagination, Wyman engages with a host of daunting contemporary concerns. Among them, arguably, are seven particularly consequential ones. First is the need for Canada to reshape its cultural destiny. Second is the crucial role of Indigenous peoples and “demands for social rebalance and redress” through “the inclusion of Indigenous and diverse creative expression“. Equally pressing, and third, is the need to reduce the storm of ideological and political conflict in contemporary life: “an ecosystem where the sense of identity conflict is all-consuming”. Next is the need to challenge policy decisions made by those in power, whether in the form of governments (on all levels), or in the form of educational bodies. All of these contemporary concerns are given additional urgency because of three final phenomena–the debilitating effects of the Covid pandemic, the impact of social media and, last, the spectre of Artificial Intelligence. Clearly, Wyman’s scope is nothing if not mind-expandingly broad: his own term, “seething complexity”, is almost an understatement.

All of these pressures feed into a monumental work both of daunting analysis and of impassioned argument. It is difficult to come away from this book without wondering whether there is anyone other than Max Wyman who could have written it. The sheer level of knowledge is jaw-dropping. Where could he have found the time, without a team of researchers, to learn, for example, of so many artists’ points of view, so many educationalists’ experiments, so many governing bodies’ shifts in policy?

It isn’t just this mountain of knowledge that adds authority to Wyman’s voice. Several other factors play into the impact of this book. First is the author’s way of humanizing and personalizing his own voice though never miring the book in his own personal story: his writing on the importance of dance in his own cultural life is especially moving. Second is the way he lets slip (and that’s all he does) the important roles he himself has played in consequential positions in Canadian and international cultural life, what he calls “hands-on experiences in Canada’s cultural trenches”. Besides being the author of many books, he was, amongst other things, President of the Canadian Commission for UNESCO. Third is his writing style. The language ranges from almost chatty and playful at times, to sombrely earnest at others, to acidly ironic at a few places, and, most memorably, to resonantly elevated and almost lyrical in the most deeply felt passages: “art takes you by the hand and walks you through the spiritual maze of existence.”

Initially, some readers might be concerned by what Wyman seems to mean by “culture” or “the arts”. At first it seems that he means “high culture”–the obvious panoply of painting, sculpture, dance, music, and, possibly, literature. While this seems to be partially the case, as the book progresses and especially when the author looks at inventive programmes initiated in communities and schools, and even more especially when those programmes involve public creativity, it is clear that his support of the arts is broadly inclusive. In academic terms, the arts become allied with “the humanities” in general. Likewise, he seems to include such “crafts” as ceramics, metalwork, and fabric arts and, later cinema, photography, publishing, recording industries and communications technology. Less obviously, though, he also considers such popular interests as comic books and digital technology. Perhaps wisely, while acknowledging that music is apparently the most wide-reaching art form in Canada, he doesn’t spell out what he considers beyond the pale of “music”! What does he think of the role of “death metal” music in Canadian culture? Or financially successful and popular “stars” like Shania Twain? We never find out.

We? Who “we” are varies enormously in this consideration of the interplay between the public and the artist. Insightfully, Wyman generally avoids identifying “them” (except, of course, when “they” are contemptible.) By consistently using “we”, he manages at different times to mean “we, humanity”, at others “we, Canadians”, “we, non-marginalized Canadians”, “we, voters”, “we, consumers of art” and so on. By saying “We should”, “we must”, “we need to” his words resonate rather than hector. “We”, the readers, Wyman makes sure, feel personally involved.

Equally important to the overall force of the book is the highly structured way in which Wyman marshals the swarms of issues and illustrative examples. Given the intelligence that radiates through every sentence, it is not the least bit surprising that the author has arranged his ideas and issues into a sequence that effectively leads to a conclusion that it would be hard for even a hard-bitten cynic to ignore (though there remains the frustrating likelihood that few arts-cynics are likely even to pick up the book).

The book is so stuffed with issues and ideas that it is impossible to do much more than touch on a few here. In the most simplified terms, the book begins with powerfully resonant statements of the transformative and uplifting effects of the arts. Balancing these properties of the artistic life are ones that are even closer to the core of Wyman’s method and ones that connect the word “compassion” in the title with the words “functioning democracy” in the subtitle. Against a backdrop of deep social polarization, Wyman unfurls the flag of “compassion”. And to create therefore a sense of the healing powers of the arts, it becomes his business to establish the ability of the arts to overcome antagonism towards the “other”. As eloquent as Wyman himself is, however, he realizes that no individual voice will be as strong as quotations from a chorus of like-minded–and respected–others. These he delivers in spades.

With this groundwork established, he then leads his readers to consider two particular negative forces (among many) that would impede the flourishing of the arts. One of these is peopled by those–ideological feet firmly planted in the firmament of economic “progress”–who cut, cut and cut–cut educational budgets in the arts, cut public funding for artists, and cut possibilities of the public even experiencing the arts. In these terms, the author identifies one of the most deadening forces to be the recent prioritization of STEM — Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. Wise enough to know that there is nothing to be gained by running headlong into this juggernaut, but also broad-minded enough to understand the need for well-rounded social and personal development, Wyman argues that STEM should become STEAM with the A representing “arts and humanities”.

Perhaps the second most powerful dark force that would cripple the arts, as most readers would quickly anticipate, is the cynical dismissal of any supposed social benefit that cannot be quantified and measured–“insistence on proof of measurable social usefulness”. He writes angrily, “We are imprisoned by our society’s need to measure and quantify….” This is where Wyman’s research is probably most crucial. This is also, therefore, where he musters study after study, initiative after initiative, spokesman after spokesman to make crystal clear that the evidence is incontrovertible: in terms of mental health, in terms of social harmony, in terms of just about any metric a social analyst could consider, the arts, Wyman demonstrates, are not a decoration on the fringes of a healthy society (and “functioning democracy”) but part of its very foundation.

Pushing forward towards the end of the book, the author makes sure that his readers–Canadian readers in particular–become aware of the history of governmental positions and counter-positions in relation to the arts in Canada. The picture is not, generally, very pretty. “Snatching a bleeding haunch of meat from a ravenous hyena would be child’s play compared to the task of prying the grasping hands of power from control of the cultural cash box.” Point made? Point made. However–and crucially– the exceptions he musters are compelling enough to lend force to the sense that, far from being a lone voice crying in the wilderness, Wyman is joined by a chorus of other enlightened voices.

Where the book strikes out most boldly on its own, though, appears in the final chapter. As the climax of the book, this chapter is a challenge and a proposal–a call not just to action but to a very specific form of action. As the extension of what Wyman terms a new Canadian Cultural Contract between the government of Canada and the people it serves, he calls for a body he calls The Canadian Foundation for Culture. In essence, a “Truly pan-Canadian outreach and collaboration will be baked into everything this agency does,” including even something like a “National Artistic Treasures program.” Unsurprisingly, this is no “pie-in-the-sky” (the author’s term) series of ideals: it is a tautly organized series of propositions and concerns, including such issues as the nature of funding, the role of the private sector, and the process of distributing benefits to creators.

It is, nevertheless, characteristic of the fundamental humility of the author, and the way he values voices beyond his own and beyond even Canadian culture, that he leaves the very last words in the book to the inspirational words of much-admired cellist Yo Yo Ma: “Culture is the foundation on which we will imagine and build a world in which we reaffirm our commitment to equality and safety for all, we act with empathy, and we know that we can always do better.” It is hard not to hear echoes of Stephen Dedalus, the protagonist of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, determined to “forge…the uncreated conscience of my race.”

[Editor’s Note: Max Wyman’s The Compassionate Imagination: How the arts are central to a functioning democracy is a 2023 finalist for the Balsillie Prize for Public Policy]

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at the University of Victoria. [Editor’s note: Theo Dombrowski has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), and Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has recently reviewed books by Dustin Cole, Deborah Willis, Lindsay Wong, Bill Engleson, Dan Gawthrop, Lyndon Grove, Ihor Holubizky, & Brent Raycroft for BCR. Theo Dombrowski lives at Nanoose Bay. Visit his website here.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “What is the role of art?”