When there are no words

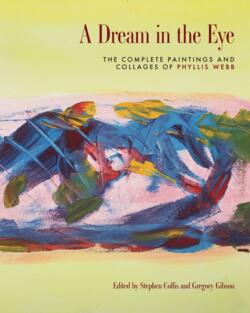

A Dream in the Eye: The Complete Paintings and Collages of Phyllis Webb

edited by Stephen Collis

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2023

$39.95 / 9781772014334

Reviewed by Mary Ann Moore

*

Artist Georgia O’Keeffe said she could say things with colour and shapes that she couldn’t say any other way – things she had no words for. Perhaps the same could be said of Phyllis Webb.

In 1950, Phyllis Webb moved to Montreal and had something like a mystical experience that revealed to her that her destiny was to be a poet. She published ten collections of poetry and prose (between 1954 and 1990) and co-founded the CBC Radio program Ideas (in 1965).

It was when “words more or less abandoned” her that Webb took up photography, photocollage, and eventually painting in the early nineties. Her concerns were those she had explored in her poetry and then expanded upon: “The natural world of the West Coast, global political strife, the artist’s struggle to express themself.”

Webb bought a camera, “an inexpensive, fully automatic Minolta Riva 35, and began to see in a subtly different way. Or had I begun to see in a different way and then bought the camera?” I appreciate the questions Webb asked herself and her humour in her essay “Might-Have-Been: The Tedious Shores” (1993) included in A Dream in the Eye.

The title of the book is from the poem “Following,” included in Webb’s Peacock Blue: The Collected Poems.

It is indeed a pleasure and delight to take in the vivid colour, patterns, shapes and subjects of Webb’s seventy-four paintings and eighty collages in this beautiful volume. Poet and artist Diana Hayes who was a close friend of Webb’s and lives on ĆUÁN (čuʔén) Salt Spring Island, specifically unceded W̱ENÁ¸NEĆ (xʷən̕en̕əč) Territory, Fulford Harbour where Webb lived since the early seventies, arranged the photographing of Webb’s visual work including pieces in private collections.

As Stephen Collis points out in his Introduction, Webb had one solo exhibition of her art which was at the Salt Spring Library.

Collis visited Webb, a poet “through and through,” in her Salt Spring home frequently and writes: “Even once words had abandoned her, throughout the almost twenty years that I knew her and visited her home and we sat amid her paintings – on her walls, stacked on against or behind the furniture and bookshelves, always moving, always repositioned so something new could be seen for a time – poetry was a presence (sometimes a painful one, because of her silence and doubt), sometimes a simple joy (the pleasure she took in reading the work of others).”

In his book, Almost Islands: Phyllis Webb and the Pursuit of the Unwritten, Collis said of himself: “I am a poet attracted to another poet for her bracing independence and her life lived long and alone, according to her own idiosyncratic definition of freedom – obedient only to her own fraught complexity.”

Collis wonders, in his introduction to A Dream in the Eye, about “what is carried over from one practice to the other – what remains of the old practice in the new? Webb’s paintings often investigate the vacated space of language – sometimes figured through her use of the crossword puzzle grid – as well as the mechanics of ‘printing,’ as seen in her frequent use of a scrap of plastic bathmat that she pressed into the surface of the painting canvas, creating another grid, this time of small, square depressions in the paint.”

The cover painting is untitled, acrylic on canvas, from 2006. It’s an example of, as Collis points out, “the joy of allowing colour to be the dominant experience of the work.” Naming some examples of canvasses including Deeper into the Forest #2 with its “earth and arboreal palette,” Collis says: “This is where wordlessness becomes pure joy . . .”

One of my favourites is The Frozen Sea Within, 2002, acrylic and collage on canvas. There is a two-page spread of the painting in the beginning of the book. I’m intrigued by the large peak that extends to the bottom rather than as expected, to the top.

Webb didn’t live long enough to carry out her plan (she died in November 2021) but when she heard, in the summer 2021, about the unmarked graves of Indigenous children being discovered on the grounds of several former residential schools, she wanted to return her Order of Canada to the Governor General . . .” As Collis says: “Her entire body of work is an ethical, metaphysical, and political attempt to respond, rigorously, to the world her own life was entangled with.”

In her “Artist Statement” (2002) that precedes her paintings, Webb says she was “sixty-six and getting creaky” when she started painting and liked to “explore a concept through a series of paintings.”

When you read her words, you can understand why she may not have found it necessary to seek out galleries to represent her: “Because I am totally self-taught, I hesitate to see all this activity as anything more than pure process, mainly learning process, or to call myself an artist. I paint, I say. I used to write, I say, but now I paint. It makes me happy.”

Laurie White’s essay, “The Phenomenal Close-Up: Abstraction as Enmeshment in Phyllis Webb’s Photocollage (2023),” precedes the section of Webb’s collages. The divisions in the book are gorgeous in themselves as there are pages of full colour in the book designed by Typesmith.

Laurie White is a curator and writer from Sheffield, UK currently based in Vancouver on unceded xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Territories and a Ph.D. student in art history at the University of British Columbia.

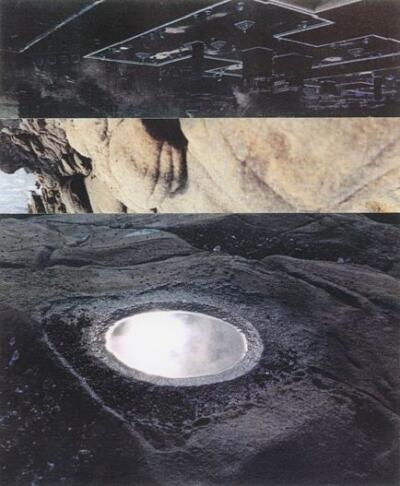

She makes note of Webb’s Fulford Harbour Series, Night Space, Tibetan Desire and Wilson’s Bowl. “The Bowl” is significant to Webb’s poetry as well as she wrote a poem by that title included in her collection of poetry, Wilson’s Bowl.

Webb wrote in her own essay of how the motif of the circle emerged as a dominant theme in her work: “moons, suns, gongs, bicycle wheels.” As White says in her exploration of “Abstraction as Enmeshment”: “The motif of meditation, evoked through the petroglyph bowl and the Tibetan gong, takes on special significance when seen alongside Webb’s own description of the collage process. For her, it was a way to experience a sense of self that was paradoxically about an education of the self.”

The bowl in the four collages entitled Wilson’s Bowl “shimmers as the surface of the water within it reflects the moon overhead.” The “bowl” is a petroglyph, a circular carved depression in bedrock in Ganges Harbour on Salt Spring Island, named by Webb and her friends for British Columbia anthropologist Wilson Duff.

As Stephen Collis points out in his book, Almost Islands, the SENĆOŦEN (Saanich) word for Ganges Harbour is SYOW̱T which means “go with caution.” As Collis writes: “So really it is SYOW̱T’s Bowl, not Wilson’s.”

White says that as Stephen Collis has argued “abstraction is an especially fertile mode through which to explore enmeshment, because it is through a close engagement with the properties of one’s medium that one comes to recognize the expressive qualities of materials as at least the equal to the artist’s subjectivity.” In Webb’s own words: “Subject/self is only expressive in and through its object/materials, to the point where there is a primary communication between the two.” (from Phyllis Webb and the Common Good by Stephen Collis)

Diana Hayes, the documentation coordinator for the book, has also written poems inspired by Webb’s paintings published as Gold in the Shadow: Twenty-Two Ghazals and a Cento for Phyllis Webb. Seven of the poems are included in the book with the first referring to “SYOW̱T’s stone bowl floods, the opal moon’s salinity.”

While words may have more or less abandoned Webb, it is such a tribute to her poetry and her visual work to read the poems by Hayes that are alive with the colour of language.

In her essay, “Phyllis Webb and the Spirit of Inquiry” (1993, revised 2005), Betsy Warland writes that she believes “that Webb’s shift may well confirm a very important aspect in the creative process, which is the spirit of inquiry. This spirit of inquiry may well be more important than the form or even the content of the artwork.”

Warland trained as a painter, a practice she “abandoned” to become a professional writer. She has been a professional manuscript consultant and editor for the past thirty years. Her essay is a thought-provoking addition to the book, paying homage to Webb’s visual art and poetry particularly the visionary aspect of a collection called Hanging Fire.

The last essay and the final words in the book devoted to her visual art is Phyllis Webb’s referred to earlier: “Might-Have-Been: The Tedious Shores.”

We are so fortunate to have Phyllis Webb’s own words, her visual art and her vision celebrated and honoured predominantly by the people who knew her well. As she reflected in her essay about might-have-beens, she wondered about former lives and “earlier existences”: “Among these possible life contrivances is there an artist, brush in hand, painting a gong, a bowl, a spinning sun or wheel?”

It hardly matters she says and quotes Charles Lamb from “Dream Children”: “We are nothing; less than nothing; and dreams.”

*

Mary Ann Moore is a poet, writer and writing mentor who lives on the unceded lands of the Snuneymuxw First Nation in Nanaimo. Her full-length book of poetry is Fishing for Mermaids (Leaf Press, 2014) and she has a new chapbook of poems called Mending (house of appleton). Moore leads writing circles and has two writing resources: Writing to Map Your Spiritual Journey (International Association for Journal Writing) and Writing Home: A Whole Life Practice (Flying Mermaids Studio). She writes a blog here. [Editor’s note: Mary Ann Moore has also reviewed books by Maria Coffey, Lorna Crozier, Katherine Palmer Gordon, Donna McCart Sharkey & Arleen Paré, Michelle Poirier Brown, and Celia Haig-Brown, Garry Gottfriedson, Randy Fred, & the KIRS Survivors for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “When there are no words”