1969 Advice to a teen girl

Skid Dogs

by Emelia Symington-Fedy

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2023

$26.95 / 9781771623643

Reviewed by Catherine Owen

*

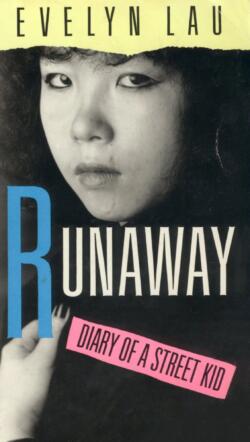

You know a book is both meant for you as a reader and well-written when you feel regular twinges of discomfiting self-recognition as the story sinks into your blood. I can’t remember the last time I read a book that so accurately and painfully reminded me of my own adolescence, even if mine was in Vancouver and that of Skid Dogs takes place mostly in Armstrong. Evelyn Lau’s Runaway and Yasuko Thanh’s Mistakes to Run with, say, were too extreme in their evocation of sex work and drug addiction to be relatable to a typical teen girl of the era. Skid Dogs bares the hum-drum awfulness of just being female as one’s sexuality burgeons in the shadow of male aggression, misinformation, the accepted ecosystem of misogyny. Emilia Symington-Fedy was lucky enough to be part of a group of girls who had her back, much of the time at least prior to the later grades, and who gave her a sense of being a collective sufferer of often unwanted male attention and both the random and planned agonies of the female body. I recall much more isolation, my hormones and low self-esteem driving me directly into a male world that excluded other girls as they were potential rivals or just simply didn’t provide that fucked dopamine rush of being wanted by boys, however momentarily.

You know a book is both meant for you as a reader and well-written when you feel regular twinges of discomfiting self-recognition as the story sinks into your blood. I can’t remember the last time I read a book that so accurately and painfully reminded me of my own adolescence, even if mine was in Vancouver and that of Skid Dogs takes place mostly in Armstrong. Evelyn Lau’s Runaway and Yasuko Thanh’s Mistakes to Run with, say, were too extreme in their evocation of sex work and drug addiction to be relatable to a typical teen girl of the era. Skid Dogs bares the hum-drum awfulness of just being female as one’s sexuality burgeons in the shadow of male aggression, misinformation, the accepted ecosystem of misogyny. Emilia Symington-Fedy was lucky enough to be part of a group of girls who had her back, much of the time at least prior to the later grades, and who gave her a sense of being a collective sufferer of often unwanted male attention and both the random and planned agonies of the female body. I recall much more isolation, my hormones and low self-esteem driving me directly into a male world that excluded other girls as they were potential rivals or just simply didn’t provide that fucked dopamine rush of being wanted by boys, however momentarily.

Skid Dogs, a memoir that reads like a page-flipper of a novel, veers back and forth between two temporalities: the first is 2011-2013 post-murder of a teen girl, Taylor, on the tracks in Armstrong as Symington-Fedy’s mother is dying slowly from cancer, and she must return regularly to care for her while, at the same time, straining to create a documentary on the tragedy, and 1991-1996, Symington-Fedy’s high school years in Armstrong, during which she meets the “girl gang” of Bugsy, Aimes, Cristal and Max, struggles to navigate pledges, sexuality, shame, the drinking culture, school, her younger brother Grum’s presence, and her mother’s initial cancer diagnosis, along with other issues resulting from her parents’ divorce and her own rebellious tendencies. At first, I had a little trouble flowing into the tale and becoming connected to the characters, as the allusiveness of the era overwhelmed, the familiarity in references to Esprit and Les Mis and Du Mauriers and slushies at Sev. Everything blended into consumer brands and the senses. However, before long I was compelled by both trajectories. Here’s a sample from each timeframe to give an idea of Symington-Fedy’s facility with sketching engaging scenes:

1991 on the first time Em gets drunk:

Tilting back, I drank three big gulps. My eyes watered fire. Leaning forward, hands on my knees, I dry-heaved but didn’t puke…The sky was light blue, on its way to dusk, and the air smelled of the sticky buds that grew along the ditch…I chugged until my stomach burned.

2012 on the state of Armstrong once the killer is apprehended:

As if a lid has been lifted off our valley….We must look like a town of foals, wobbling around on too-long legs…the wanted posters are ripped down…Even the staples are taken out of the telephone poles. Engines rev as kids open up their garages…[but] even though the new lights that hang along the fenceline are bright, they don’t penetrate the shade that edges the path.

In both these randomly-selected excerpts, one can hear the poetic talents at play in the prose, the consciousness of sound in knees/heaved or penetrate/shade, the focus on the crucial senses through which one can more wholly enter any experience and the similes, such as the comparison of the townspeople to foals, that serve to enlarge and deepen the vision of this key moment of release and re-birth within traumatic times. The Douglas and McIntyre Press Kit interview with Symington-Fedy is incredibly poignant in revealing her hopes for this memoir. She states that her intention in writing this book is so “the fourteen-year-old girl like me out there might make different choices…to witness that 30 years later, this mishandling of their bodies now, will be a problem. They will have long-term pain.” And although I doubt somewhat whether a 14-year-old would be able to truly absorb the lessons in this vital narrative, I know that for myself as a reader around Symington-Fedy’s age, it was brutally essential for me to re-envision that time when so much impact happened that felt like nothing, but that became immeasurably much in the future.

I almost felt embarrassed at my younger self who also believed, as the narrator recounts, that girls are instant sluts for yielding to male incursions (“Twyla was the first official slut of grade eight…She’d put herself in a no-win situation by being alone with him in the first place…all the dick licking and bikini-line waxing she’d have to do now”), that if a girl yields to sex then she will ensure commitment from a boy (“A hot liquid shot out of his penis down the back of my throat…I wiped my mouth…He likes me. He’ll want more”), that girls aren’t supposed to receive wanted pleasure but must see sex as “the action of ticking another box off the list,” and that even in adulthood, sex is the tool of assurance and power, as when into her thirties, the narrator thinks an “old thought” while she’s worried about her new partner’s core fidelity to her: “If I sucked his dick he’d come over just fine.” I truly don’t remember ever reading such poignant and raw summations of the irrefutable toxicity of being female in this culture of male entitlements. The notion that a girl is fixed in a reputation, whether based on truths or fables, from the get-go and will have a hard time, perhaps even a lifetime’s worth, of shaking it or persisting in a state of determined indifference. As Max comments nearer to the memoir’s end, reflecting on the above-mentioned Twyla’s pigeon-holing as a slut: “I just wonder who gets to make these decisions, ya know?”

Today, it’s even scarier for teen girls in certain ways, as while they may have more information (we had so little in the late 80s/early 90s in Catholic school that many girls in the class got VDs and/or pregnant. Em, at least, evinces much awareness of birth control in the tale!), there is more pressure to sexualize themselves from social media, and more evidence of their potentially sordid activities that can haunt them for the rest of their lives. Women of my generation frequently comment to each other how lucky we were that there’s no media proof of our abuse. Wow, how fortunate we are (she muses sarcastically). The only “dignity” the narrator seems to discover for herself as a needy teen is by becoming the one who is “ravenous,” not the one who is passive and thus, powerless. Oh, how relatable. Yikes. I won’t tell you how the memoir ends but it’s full of hope for a healing between generations, spouses, friends, and, most importantly, with the self. Skid Dogs (the teasing name the girls eventually dub each other) is rich with harshness and yes, with humour, which Symington-Fedy calls, in the Press Kit interview, “revolutionary” and also, “a sharp weapon when needed, too.”

*

Catherine Owen was born and raised in Vancouver by an ex-nun and a truck driver. The oldest of five children, she began writing at three and started publishing at eleven, a short story in a Catholic Schools writing contest chapbook. She did her first public poetry readings in her teens and Exile Editions published her poetry collection on Egon Schiele in 1998. Since then, she’s released fifteen collections of poetry and prose, including essays, memoirs, short fiction and children’s books. Her latest books are Riven (poems from ECW 2020) and Locations of Grief (mourning memoirs from 24 writers out from Wolsak & Wynn, 2020). She also runs Marrow Reviews on WordPress, the podcast Ms Lyric’s Poetry Outlaws, the YouTube channel The Reading Queen and the performance series, 94th Street Trobairitz. She’s been on 12 cross-Canada tours, played bass in metal bands, worked in BC Film Props and currently runs an editing business out of her 1905 house in Edmonton where she lives with four cats. Editor’s note: Catherine Owen has also reviewed books by Sean Kelly, Jason Schreurs, Adrienne Fitzpatrick, Connie Kuhns, Hilary Peach, and John Armstrong for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1969 Advice to a teen girl”

Catherine,

What a gift as an author to be gotten. Thank you for this dead-on review.

* Tiny typo 1996 Advice to a Teen Girl