1917 Teenage wasteland, Y2K bromance

New Millennium Boyz

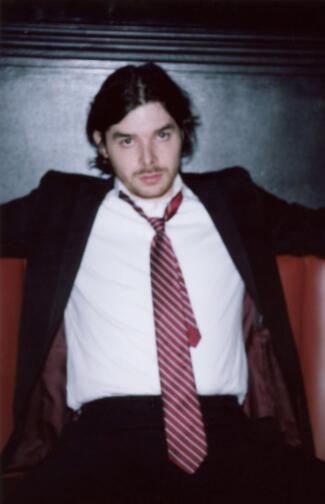

By Alex Kazemi

New York: Permuted Press, 2023

$37 / 9781637583913

Reviewed by Daniel Gawthrop

*

In some ways, Brad Seela is a typical seventeen-year-old white boy coasting through an apathetic life in the suburban North America of 1999: bored with school, indifferent about the future, disillusioned with his yuppie parents, susceptible to peer pressure, vulnerable to excessive drug use, and constantly horny.

In some ways, Brad Seela is a typical seventeen-year-old white boy coasting through an apathetic life in the suburban North America of 1999: bored with school, indifferent about the future, disillusioned with his yuppie parents, susceptible to peer pressure, vulnerable to excessive drug use, and constantly horny.

In New Millennium Boyz, the debut novel of Vancouver-based 29-year-old artist and writer Alex Kazemi, we watch as Brad—falling under the bad influence of two shady transfer students to his school—sees his life spin out of control. The novel, ten years in the making, is pitched as a critical look at Y2K “bro” culture, toxic masculinity, and the soul-deadening effects of MTV consumerism and early Internet culture on fragile young minds like Brad’s. The result is an unsettling glimpse into the kind of alienation that enables tragedies like the Columbine massacre.

It’s a good premise for a novel, and Kazemi—who grew up in Vancouver and was only five years old in 1999—has done his research. But NMB is an excruciating read, thanks to conventions of high-risk lit that the author exploits to the max: unrelenting passages of profanity-laced prose filled with offensive content and unsympathetic characters who brandish their outsider cred while celebrating their own racism, misogyny, and homophobia as flag-waving virtues. It’s a lot to stomach because this kind of fiction relies completely on dialogue to move the story along.

Nearly all the conversations are between high school kids, so the reader must endure page after page of potty-mouthed teenspeak: accelerated chatter in which boys share their fantasies about girls’ “jugs,” “titties,” and “pussies” (in this particular bro culture, the words “sick,” “cool,” “dope,” and “chopped” become hyperbolic substitutes for “awesome,” itself a tired surfer dude replacement for “great” or “excellent”); girls, meanwhile, share their fantasies of Leo DiCaprio in The Basketball Diaries or Ewan McGregor in Trainspotting—“a guy who looks like he just left a heroin detox clinic. Ugh. So fucking hot!”

The narrative moves at a rapid pace, but the reading experience feels voyeuristic. The biggest problem is Brad himself: by signalling his lack of compassion for those of lesser privilege, and his willingness to tell whatever lies necessary to get what he wants, the novel’s main protagonist exposes himself as utterly amoral. At one point, he muses: “I think one of the most beautiful words in this language is ‘Whatever.’ It captures how I feel about everything.”

Perhaps Kazemi is milking his main character for satirical effect here. But if Brad is really that vacant a person—and we’re shown this from the outset—it’s hard to care about him. When he and his buddies terrorize a girl with Down syndrome, bully and intimidate an Asian boy, or film a snuff video of killing a rat, we don’t empathize with his ennui. We’re just disgusted.

Brad’s new friends, Lu and Shane, are Baphomet-worshipping outcasts who draw him into satanic, borderline SM rituals they capture on video. Lu is the kind of dissolute youth who relieves his schoolyard boredom by drawing swastikas in the boys’ washroom. Waxing like Ayn Rand as he shares the latest thrill of his individualist “aesthetic,” he gaslights Shane about his depression, revealing cracks in their friendship by telling him to get over it. Gradually he develops an increasing hold over Brad, alternately welcoming his company and calling him out for being phoney and too concerned with other people’s opinions of him.

There are two comical aspects of NMB that work. The first is how Kazemi breaks up the bromance scenes with written correspondence between Brad and Aurora, a girl he met at summer camp. Their early letters, eager to recapture their brief shining moment of sexual intercourse, are filled with typical teenaged longing. But Brad’s efforts to win Aurora’s heart require him to tell outrageous lies: not long after he attends a rave where he beats the living shit out of a guy tripping on ‘E’ who offers him a blowjob, Brad tells Aurora that he “witnessed a brutal act of homophobic violence” at a party and that “I kind of want to join the GSA my school just started.” (Aurora, impressed by an action he has no intention of taking, tells him that membership in a gay-straight alliance “will look great” on his application to Berkeley.) The other is how Kazemi’s treatment of toxic masculinity reinforces conventional wisdom about homophobia: that the most violent gaybashers, and young men who can’t stop talking about “faggots,” “homos,” “fudgepackers,” and “queers” are most likely tormented closet cases. This becomes clear as Brad’s connection to Lu (short for Lusif, a nudge-nudge for Lucifer) deepens.

For a guy who’s so into women, Brad spends a lot of time thinking about shirtless boys with perfect bodies. His attention to detail in describing hot male beauty, witnessed earlier in the novel with his accounts of changing room and summer camp scenes, is as highly attuned as that of a seasoned gay pornographer. After he meets Lu and Shane, women disappear from the scene. Once the depressive Shane is out of the picture and Brad is alone with Lu, their physical intimacy becomes as gay as it’s possible to be without actually bonking. Although their glaring hypocrisy is funny to witness, the possibility that Brad has found his true soul mate in Lu is grim to contemplate as the novel races toward its horrifying climax.

*

Chock full of profanity, vulgarity, and bad behaviour throughout, NMB made me feel like I needed a shower after reading it. That effect may have been deliberate on Kazemi’s part. But after 326 pages, it’s hard to imagine teenagers actually talking like this—“I’d rather stick a McDick’s straw up Matt Damon’s cornhole and suck his queefs out than be at school right now”—and sometimes it seems as though the cascade of Y2K cultural references and arch ironic posturing were created for effect only. But then, NMB is not targeted for Late Boomer gay men like this reviewer, for whom Dennis Cooper covered similar ground in the Nineties with novels like Closer, Frisk, and Try.

One can’t help but be impressed by some of the big names (Bret Easton Ellis, Douglas Coupland, Ellen Hopkins, etc.), and even Columbine survivors, who have lined up to praise NMB. Still, the content warning at the beginning of the book—demanded by sales reps, according to Kazemi’s publicist, “fearing that teenagers would re-enact or fetishize the behavior displayed by its characters”—seems misplaced. It isn’t teenaged boys who might gobble up this book, after all, but Millennials and grad students of pop culture and media studies.

*

Daniel Gawthrop debut novel, Double Karma, which is set mostly in Burma/Myanmar, was published this spring by Cormorant Books. He’s also the author of five non-fiction titles including The Rice Queen Diaries, a memoir about interracial attraction. Visit his website here. [Editor’s note: Daniel Gawthrop has recently reviewed books by Charlotte Gill, Eden Robinson, Tsering Yangzom Lama, Alan Haig-Brown, Anthony Varesi, Corey Hirsch, and Harley Rustad for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1917 Teenage wasteland, Y2K bromance”