1859 A career tracking an elusive creature

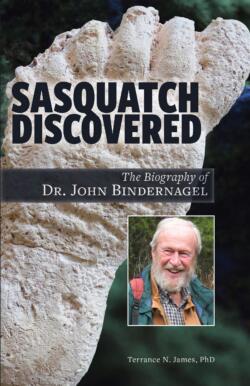

Sasquatch Discovered: The Biography of Dr. John Bindernagel

by Terrance N. James, PhD.

Surrey, B.C.: Hancock House, 2022

$26.95 / 9780888397515

Reviewed by Ken Favrholdt

*

Sasquatch seems to be everywhere in our daily lives, or mine anyways. My wife Linda recently purchased a block of “Sasquatch Trails” ice cream, a blend of chocolate and vanilla with small peanut butter cups. Sasquatch are found on t-shirts, key chains, bags, and all manner of paraphernalia. Of course, there are countless books about this ape-like creature, known as Bigfoot in the United States, and Yeti in Asia. There are, according to James, an internet search of the word Sasquatch produces 11.8 million hits in less than a minute.

Sasquatch seems to be everywhere in our daily lives, or mine anyways. My wife Linda recently purchased a block of “Sasquatch Trails” ice cream, a blend of chocolate and vanilla with small peanut butter cups. Sasquatch are found on t-shirts, key chains, bags, and all manner of paraphernalia. Of course, there are countless books about this ape-like creature, known as Bigfoot in the United States, and Yeti in Asia. There are, according to James, an internet search of the word Sasquatch produces 11.8 million hits in less than a minute.

A recent publication by Hancock House, Sasquatch Discovered. The Biography of Dr. John Bindernagel, is one of the most convincing and fascinating overviews of the creature I have read. Written by Terrance James, a retired educator and long-time friend of Dr. John Bindernagel, he follows in a biographical, chronological fashion the footsteps of Bindernagel and his gradual exposure to the elusive creature. Born in Kitchener Ontario, Bindernagel and his family moved to British Columbia in 1975. There are numerous photographs and illustrations that follow the story and people of Bingernagel’s life.

More than a descriptive overview of sasquatch sightings, the book is a criticism of those individuals, including scientists, who dismiss the evidence and halt their investigation for lack of what they call proof. The book presents a challenge to readers: “What happens when a very credible scientist chooses to study an animal which scientific colleagues and the general public do not believe even exists?”

The biography is divided into three parts – the first part following Bindernagel’s education and early career, beginning as a naturalist interested in wildlife conservation, then studying wildlife biology, obtaining a PhD, and becoming a consultant. He travelled to far-flung parts of the world including Uganda, Tanzania, Iran, the Caribbean, Belize, southern Africa and Nepal, where he finally learned about Yeti. The second part describes his passion. He spent increasingly more time studying the sasquatch from his home in the Cowichan Valley on Vancouver Island where he lived with his family for forty years. The last part covers his legacy – his discoveries and the accolades he received from fellow researchers.

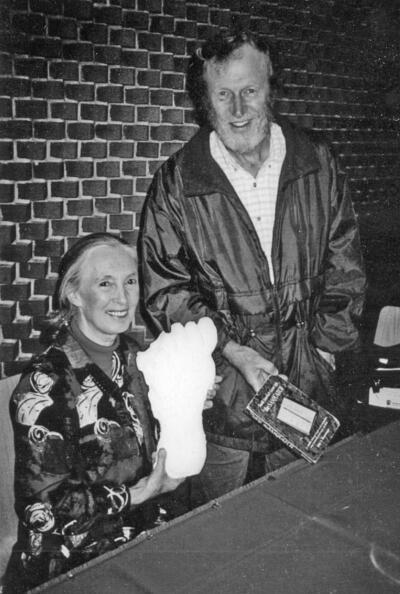

Bindernagel first contemplated writing a book in the early ‘90s, titled North America’s Great Ape: The Sasquatch which appeared in 1998. It gained some attention including by Dr. Jane Goodall, the famous British primatologist who wrote: “I find it exciting that, finally, a book has been written that accepts (rather than trying to prove) the existence of the Sasquatch …” He met her in Africa in 1999. “The conclusion that the sasquatch was North America’s great ape seemed so self-evident to John….”

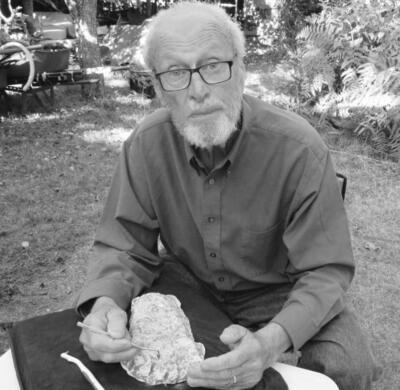

The biography is much more than the life of Bindernagel, his meetings with fellow researchers, his friend and mentor researcher John Green, and René Dahinden a charismatic Swiss-born Sasquatch researcher, both advocates for advocate for the controversial Patterson–Gimlin film, shot in 1967, and John’s presentations at conferences and interviews on film. The biography is a refutation of the way that academic scientists work. He would say: “Not having evidence you would like doesn’t excuse you from examining the evidence that’s available.” At a 2013 conference Bindernagel wrote, “It is becoming increasingly clear that eventual recognition of the North American sasquatch will be credited to citizen scientists. For over half a century, it has been citizen scientists – rather than relevant biologists and other scientists – who have recorded eyewitness reports, cast sasquatch tracks (as long ago as 1941), compiled the historical evidence back to the mid 1800s, and brought the subject to the attention of the few relevant scientists willing to consider it objectively.”

Bindernagel was the quintessential scientist – keeping an open mind and carefully examining the evidence, basing his research on science. John’s second book The Discovery of the Sasquatch: Reconciling Culture, History and Science in the Discovery Process (2010) pointed out the scientific method and the importance of testing a hypothesis. “John wanted the great-ape hypothesis tested in light of accumulating evidence and interpreted according to established zoological principles”:

- If the sasquatch is corporeal, then it will leave tracks in soft substrates such as mud or wet sand.

- If the sasquatch is a great ape, then it will leave tracks resembling those of a primate.

- If the sasquatch is a great ape, then it will exhibit ape anatomical features and demonstrate elements of great ape behaviour.

To Bindernagel’s chagrin, the great-ape hypothesis was largely dismissed by scientists.

While John had a good relationship with cryptozoologists (those who study creatures whose presence is unproven such as the Ogopogo or the Loch Ness monster), Dr. Paul LeBlond, a cryptozoologist himself, stated that John did not suffer from “academic correctness.” Sasquatch was a scientifically taboo subject in 1963. “Indeed,” states James, “John abandoned the strictures of academia for the freedom of the wild, to be able to follow his passion uncensored.”

In the summer 2000 issue of British Columbia Magazine is an article by Bindernagel accompanied by a painting by Robert Bateman that Christopher Murphy describes as the “most important article on the Sasquatch ever written.” “His passion for this subject surpasses all researchers I have known. Many of us have written about the sasquatch, but John took everything to the next level – the sasquatch was real; not just probably real; and all that stated on the basis of first-hand experience,” Murphy says. James stated that “he had worked tirelessly to bring forth the story of the discovery of the sasquatch and believed that the sasquatch would someday be recognized as a species of mammal. His books, videos, presentations, and now his biography, are part of the story, part of his legacy.”

An important chapter focuses on the Aboriginal knowledge of sasquatch. The term Sasquatch itself derives from the Sts’ailes First Nation living near Harrison River and Lake in the Fraser Valley. The term, meaning “wild man or hairy man,” became popularized in 1929. But the first recorded observation of the creature may have been by fur trade explorer David Thompson while crossing the Rocky Mountains in January 1811. He and his entourage came across footprints in the snow which measured 14 inches in length by eight inches in breadth that they followed for one hundred yards.

Bindernagel enjoyed visiting First Nations communities and meeting band members to hear their stories about sasquatch, encouraging them, including Thomas Sewid of Alert Bay east of Port MacNeil on Vancouver Island, to tell their stories. Sewid is known for his television series, Aboriginal Adventures, and many appearances on sasquatch-related shows.

It was at Alert Bay that Bindernagel researched sasquatch vocalizations, using audio recording devices, and comparing the to the sound of birds using Cornell University’s on-line library. “One Alert Bay resident “was convinced the calls were from a sasquatch.”

James’ biography includes a glossary of terms, a list of Bindernagel’s research videos (available at sasquatchbiologist.org and on YouTube), a filmography, an index of names, and notes to all the chapters. James even gives a plug for Hancock House, “the leading publisher of sasquatch titles” — 30 of them written mainly by “amateur investigators.” One book I came across, Bigfoot: The Yeti and Sasquatch in Myth and Reality by John Napier (1973) is not cited by James. Napier states, “I am convinced that the Sasquatch exists, but whether it is all that it is cracked up to be is another matter altogether. There must be something in north-west America that needs explaining …”

Unfortunately, Bindernagel said himself he was running out of time to complete his work and he passed away in 2018 from cancer at age 76. “My point,” Bindernagel stated, “is that the sasquatch has been discovered, but the discovery has not been acknowledged.” Needless to say, the interest in sasquatch will continue.

James’ biography of Bindernagel is unquestionably authoritative, complete, and carefully written. James’ exuberance about his friend’s “calling” concludes by describing him as a guru, a legend, and a legacy. He undoubtedly gained the respect of his peers.

*

Ken Favrholdt is a freelance writer, historical geographer and museologist with a BA and MA (Geography, UBC), a teaching certificate (SFU), and certificates as a museum curator. He spent ten years at the Kamloops Museum & Archives, five at the Secwépemc Museum and Heritage Park, four at the Osoyoos Museum, and he is now Archivist of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. He has written extensively on local history in Kamloops This Week, the former Kamloops Daily News, the Claresholm Local Press, and other community papers. Ken has also written book reviews for BC Studies and articles for BC History, Canadian Cowboy Country Magazine, Cartographica, Cartouche, and MUSE (magazine of the Canadian Museums Association). He taught geography courses at Thompson Rivers University and edited the Canadian Encyclopedia, geography textbooks, and a commemorative history for the Town of Oliver and Osoyoos Indian Band. Ken has undertaken research for several Interior First Nations and is now working on books on the fur trade of Kamloops and the gold rush journal of John Clapperton, a Nicola Valley pioneer and Caribooite. He lives in Kamloops. Editor’s note: Ken Favrholdt has recently reviewed books by Mali Bain, Liz Bryan, Erín Moure & Anne Callison, Jeannette Armstrong, Lally Grauer, & Janet MacArthur, and Arthur Manuel & Ronald Derrickson for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1859 A career tracking an elusive creature”