1851 ‘A town without pity’

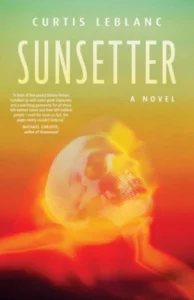

Sunsetter

By Curtis LeBlanc

Toronto: ECW Press, 2023

$22.95 / 9781770416901

Reviewed by Bill Paul

*

In the fictional prairie town of Perron, it’s a tradition for residents to attend the annual Sunsetter Rodeo and Fair held in late May. For Dallan and Brooks, two close friends in their late teens, it’s an occasion to get high on some “good clean shit for cheap.” In Sunsetter, the boys’ excitement quickly turns to tragedy. The pills (possibly Xanax or Percocet) are purchased, and after swallowing them Dallan starts to “feel a buzzing all over,” but Brooks collapses and his eyelids “twitch and flitter.” A paramedic makes his way through a crowd and tries to revive him. Brooks dies surrounded by strangers. The scene appears in the opening part of the debut novel by Vancouver’s Curtis LeBlanc. A story about a community worn down by an illicit drug market working in collusion with the local police force, the novel dramatizes a tragedy that’s familiar to communities in Canada and the United States.

In the fictional prairie town of Perron, it’s a tradition for residents to attend the annual Sunsetter Rodeo and Fair held in late May. For Dallan and Brooks, two close friends in their late teens, it’s an occasion to get high on some “good clean shit for cheap.” In Sunsetter, the boys’ excitement quickly turns to tragedy. The pills (possibly Xanax or Percocet) are purchased, and after swallowing them Dallan starts to “feel a buzzing all over,” but Brooks collapses and his eyelids “twitch and flitter.” A paramedic makes his way through a crowd and tries to revive him. Brooks dies surrounded by strangers. The scene appears in the opening part of the debut novel by Vancouver’s Curtis LeBlanc. A story about a community worn down by an illicit drug market working in collusion with the local police force, the novel dramatizes a tragedy that’s familiar to communities in Canada and the United States.

Brooks’ overdose due to contaminated drugs (“trace amounts of fentanyl”) sets the plot in motion. Upset and distressed over his friend’s death, Dallan confronts Nick, a ride operator at Sunsetter who sold him the bag of pills. Dallan’s unaware that Nick is planning to leave his job at Sunsetter and start a new life with a young, local woman named Hannah. Without giving away too much of the plot, misfortune ensues and Dallan and Hannah—two young people facing inexplicable loss—are brought together. While the parents of the teens remain on the sidelines, unaware of the recent dramatic events, the two grief-stricken teenagers, motivated by the need for justice, set out to investigate their friends’ deaths. Dallan and Hannah are unaware that larger forces are conspiring against them.

LeBlanc structures the novel around a weekend at Sunsetter (“the colourful lights that twirl in the dark sky, the smell of grease and sugar and turned-up soil … where the reek of booze and smoke carries down the main drag like a bad breeze”). In the aftermath of the tragic incidents at the fair, a police officer named Aaronson, and other officers circle the wagons and start to intimidate, harass and threaten Dallan and Hannah. A crooked policeman, Aaronson is a married man who “wonders when all the good disappeared from his life.” He’s a character defined by his feelings of hopelessness and conflicted about the compromises he’s made. An air of fatalism hangs over him and other characters; gradually, the narrative takes the shape of a crime suspense novel.

Leblanc does a good job of establishing the main characters and exploring their personalities. For example, Dallan and Hannah are shy, older, middle-class teens from stable families who dream of finding their own way in life: Dallan attending college, Hannah settling down with Nick (“pretty Nick”). Both characters have lost someone who was important for them, someone they were close to and could confide in. Dallan is overcome with memories about Brooks and the short time they spent together:

“Brooks with marinara sauce clinging to his moustache in the high school cafeteria. Brooks, next to him on his bed, drunk and alive only a few weeks ago, telling him about the person he imagined he could be if he only got it through his head that he was good, that he could be good if he tried and tried again.”

At one time the town of Perron had a booming crude oil industry that attracted migrant workers, locals and outsiders, young and old. But that boom time has run its course. LeBlanc tells of several characters in town lying low or working at two jobs trying to keep their heads above water. The very town has changed. Here’s the second storey walk-up apartment of Hannahs ne’er do well, older brother, Thomas: “Buildings like his used to house the oil field and construction workers when they first came to Perron from all over the country, even places the world-over that most people in Perron had probably never heard of. Now they’re cheap rentals for young locals or the now-unemployed who never left.”

Leblanc’s writing is full of sharp observations and insightful turns of phrases. Thomas has a “niche knowledge” of the local drug trade. A horse in a chuckwagon race is a “bottle of thunder.” Nick’s boss expects his employees to take off their boots on the “AstroTurf” outside his trailer. The novel works due to the author’s skill at developing credible characters and dialogue, and when he describes a character’s relationship to a particular place or setting in town—the alleyways behind the strip mall, the ghostly neighbourhoods, the air hot and dry. The streets where the roots of trees “search for earth and water”; a place falling into decay and lives altered and lost. As the narrative progresses, Hannah becomes a forceful character pushing back against a “sinister machine.” A young person living in a town without pity.

*

East Vancouverite Bill Paul enjoys photography and reading fiction and non-fiction. Editor’s note: Bill Paul has also reviewed books by Patrick deWitt, Barbara Fradkin, Dietrich Kalteis, Stan Rogal, Keath Fraser, and John Farrow, and contributed a photo-essay, Trevor Martin’s Vancouver, to The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

4 comments on “1851 ‘A town without pity’”