1819 The personalities behind the paper

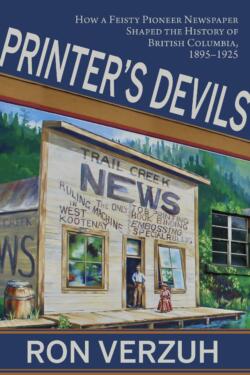

Printer’s Devils: How a Feisty Pioneer Newspaper Shaped the History of British Columbia, 1895-1925

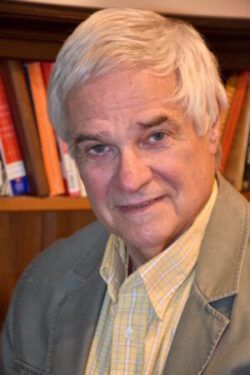

by Ron Verzuh

Qualicum Beach, BC: Caitlin Press, 2023

$28.00 / 9781773861036

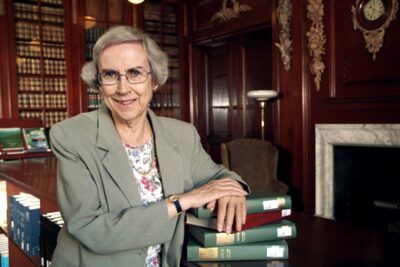

Reviewed by Patricia E. Roy

*

Small town newspapers can reveal much about the communities they serve. Indeed, Ron Verzuh suggests that Printer’s Devils “plays a double role, first as a social history and second as a history of country journalism as practised at the Trail Creek News and [its successor,] the Trail News.” (27) They ran from 1895 to 1925. Every week these papers gave residents of Trail, B.C. news of their community and something of the world beyond. Verzuh’s focus, however, is more on the editors and publishers, their personalities and opinions, than on social history. In a nice touch, the penultimate chapter recounts their careers after they left the News. “Printer’s devils” were apprentice printers who did a variety of odd jobs; most men featured were once apprentices and often continued to do the many tasks required to publish a paper. Because of rivalries between papers and the mobility of some editors, this carefully documented book includes information about other newspapers in the West Kootenay and the Boundary Country.

Small town newspapers can reveal much about the communities they serve. Indeed, Ron Verzuh suggests that Printer’s Devils “plays a double role, first as a social history and second as a history of country journalism as practised at the Trail Creek News and [its successor,] the Trail News.” (27) They ran from 1895 to 1925. Every week these papers gave residents of Trail, B.C. news of their community and something of the world beyond. Verzuh’s focus, however, is more on the editors and publishers, their personalities and opinions, than on social history. In a nice touch, the penultimate chapter recounts their careers after they left the News. “Printer’s devils” were apprentice printers who did a variety of odd jobs; most men featured were once apprentices and often continued to do the many tasks required to publish a paper. Because of rivalries between papers and the mobility of some editors, this carefully documented book includes information about other newspapers in the West Kootenay and the Boundary Country.

Given the extent of the early American influence on the West Kootenay, it is not surprising all but one editor was born in the United States where he learned the newspaper business. Only Arthur Richard Babington was Canadian-born but, as editor (1907-14) he was subservient to the owner, William K. Esling, who learned the trade in his native Philadelphia and practiced it in Washington State before coming to British Columbia where, in addition to the News, he owned and edited newspapers in Rossland. Esling, who also invested in real estate, established a Canadian presence. After eyesight problems forced him to leave journalism, he became a politician and served as a Member of the Legislature (1920-24) and of Parliament (1925-45).

While new editors might change the layout, include more or less boilerplate, or vary the quality of local reporting, their editorials had much in common. They supported the Conservative party; abhorred socialism and such radical labour organizations as the Western Federation of Miners, the One Big Union, and the Industrial Workers of the World; “boosted” Trail; and mused on the value of local newspapers and their problems. In addition, they reflected the prejudices of the time against Doukhobors, Chinese and women outside the home. Indeed, Verzuh prefaces the book with a note that he does not share these views and redacts offensive words in a few quotations.

The subtitle claims to tell “How a feisty newspaper shaped the history of British Columbia, 1895-1925.” The News was undoubtedly “feisty,” but the rest of the claim is an exaggeration, possibly made by an over-enthusiastic marketing manager since it only appears on the cover and the title page. There is no evidence of its influence extending beyond Trail and even there it was limited. Surely Consolidated Mining and Smelting (CM&S), the major employer, and its long-time president, S.G. Blaylock did more to shape the city than any newspaper. One wonders if CM&S and its parent, the Canadian Pacific Railway, had any influence on the paper apart from being regular advertisers.

Blaylock first appears as the scorer of a goal in a hockey game against Rossland and reappears through his presidency of hockey clubs and leagues, his winning of prizes for his vegetables at the Trail Fruit Fair, and reports on his health and family, More significantly, Verzuh records Blaylock’s rise through the ranks of CM&S from assay office chief, through manager of the Hall Mines Smelter, to his return to Trail as assistant managing director of CM&S, a position he held until 1919 when he became managing director.

Blaylock’s views of labour relations coincided with those of the editors. Or was it vice versa? Given Verzuh’s previous publications, it is not surprising that much of the news he reports concerns labour relations. In 1918 Blaylock praised the smelter employees for their wartime work but asserted that a few radicals fomented the 1917 strike and that the men themselves “forced the leaders to call it off.” (125) When miners at Kimberley struck in 1919, Blaylock denied them a pay raise because the price of lead would not allow it and only federal intervention settled the dispute. Verzuh describes Blaylock’s subsequent formation of the Workmen’s Co-operative Committee, essentially a company union. While Verzuh suggests that not all workers were pleased, it and periodic pay raises maintained labour peace at the smelter for over two decades.

Printer’s Devils is logically organized around editors; within chapters, strict chronology has problems. It permits the reader to see the unfolding of stories in the same sequence as the original readers but loses the historian’s advantage of being able to tell a story in a unified whole. An example are references to Tadanac whose history appears intermittently between pages 105 and 180. Smelter Hill was named “Tadanac” in 1917 but no reason is given. Some pages later it is mentioned that most of the company’s managers resided there. Four years later CM&S sought to incorporate Tadanac as a separate municipality. The city of Trail feared the loss of a tax base. The controversy persisted into the next year. Editor Elmer D. Hall favoured its incorporation while Esling, his former boss and now MLA, opposed it, presumably because of his property holdings in the city. CM&S got its way; Tadanac was incorporated. However, when the company proposed to build the new hospital there, Trail City Council, the Workers’ Committee and Hall argued it should be in Trail. In a rare event, CM&S surrendered and the Trail-Tadanac hospital was built in Trail.

A strictly chronological approach produces repetition. Every year, hockey games were won and lost; fraternal orders met; and accidents happened. Seldom, however, does Verzuh provide anything beyond the fact that the event took place. Of course, he may be at the mercy of editors who confined some news to jottings. With one exception, listing the titles of movies that played at the local theatre normally does not reveal much particular to a local community. The popularity of the racist film, The Birth of a Nation, however, supports Verzuh’s passing observations about nativism that also applied to Italians and other southern Europeans as well as to Chinese and Doukhobors.

It is not necessary, however, to list a sampling of patent medicine almost every year. (Tanlac appears eight times in the index!) Patent medicine ads were a steady source of revenue for North American newspapers but say nothing of the health of Trail residents. Two of Verzuh’s occasional extended treatments of a theme — the Spanish flu and a later debate over smallpox vaccinations — do deal with health and have echoes a century later.

Verzuh, the third generation of his family to live in Trail, knows the territory well; let us hope he turns his pen to filling out the city’s social history. As Elsie Turnbull revealed in her slim volumes on Trail’s history published many years ago[i] and as his occasional extended accounts and many snippets hint, a comprehensive social history of Trail would be an excellent addition to British Columbia historiography. In the meantime, Printer’s Devils must be welcomed as a fine contribution to the history of journalism in British Columbia.

[i] Elsie G. Turnbull, Topping’s Trail (Vancouver: Mitchell Press, 1964) and Trail Between Two Wars (Victoria: privately published, 1980).

*

Patricia E. Roy, professor emeritus of History at the University of Victoria, grew up in New Westminster. She remembers family Sunday drives through Maillardville en route to visiting Mr. McKercher, her father’s elderly friend, who retired to Haney. Patricia Roy is the author of Vancouver: An Illustrated History (Lorimer, 1980) and The Illustrated History of Canada: British Columbia. Land of Promises (Oxford University Press, 2005), with John Herd Thompson, and is known for her trilogy of books on the responses to Chinese and Japanese immigrants: A White Man’s Province (1989), The Oriental Question (2003), and The Triumph of Citizenship (2007), all published by UBC Press. Her most recent books are Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (UBC Press, 2012) and The Collectors: A History of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives (Royal BC Museum, 2018), reviewed here by Chad Reimer. Editor’s note: Patricia Roy has recently reviewed books by Daniel Francis, Grace Eiko Thomson, George M. Abbott, Jesse Donaldson, Linda Kawamoto Reid, John Endo Greenaway, & Fumiko Greenaway , and Marie-Laure Chevrier & Michael Kluckner for The British Columbia Review.

Patricia E. Roy, professor emeritus of History at the University of Victoria, grew up in New Westminster. She remembers family Sunday drives through Maillardville en route to visiting Mr. McKercher, her father’s elderly friend, who retired to Haney. Patricia Roy is the author of Vancouver: An Illustrated History (Lorimer, 1980) and The Illustrated History of Canada: British Columbia. Land of Promises (Oxford University Press, 2005), with John Herd Thompson, and is known for her trilogy of books on the responses to Chinese and Japanese immigrants: A White Man’s Province (1989), The Oriental Question (2003), and The Triumph of Citizenship (2007), all published by UBC Press. Her most recent books are Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (UBC Press, 2012) and The Collectors: A History of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives (Royal BC Museum, 2018), reviewed here by Chad Reimer. Editor’s note: Patricia Roy has recently reviewed books by Daniel Francis, Grace Eiko Thomson, George M. Abbott, Jesse Donaldson, Linda Kawamoto Reid, John Endo Greenaway, & Fumiko Greenaway , and Marie-Laure Chevrier & Michael Kluckner for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1819 The personalities behind the paper”