1801 It’s what boys do

Who Has Seen the Wind

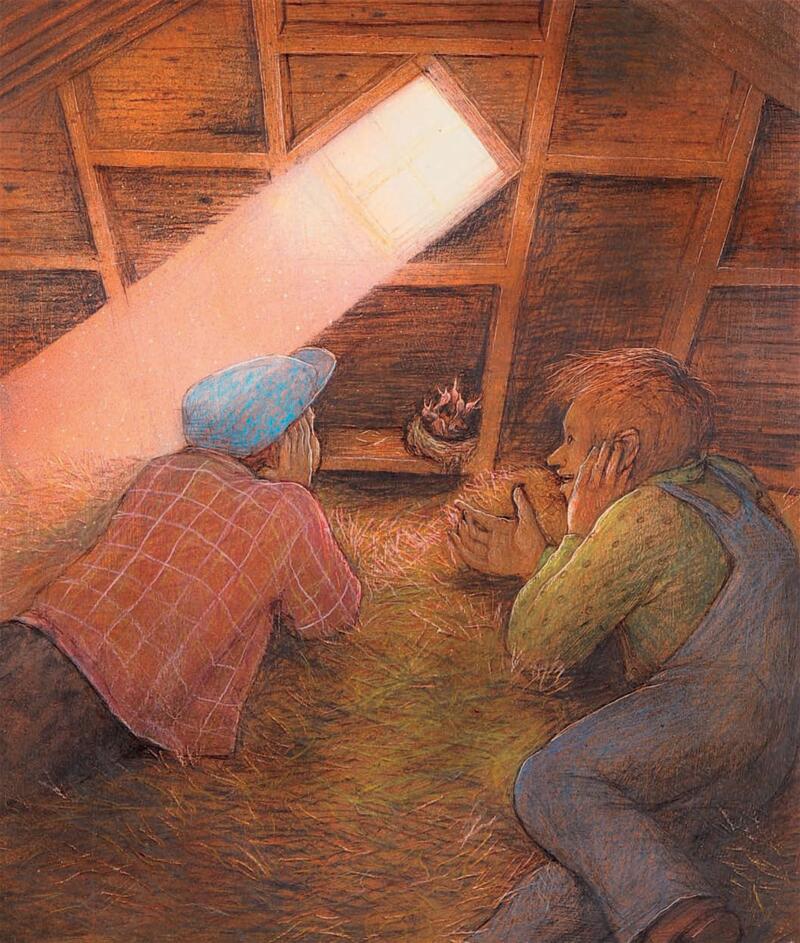

by W.O. Mitchell, illustrations by William Kurelek, 75th anniversary edition

Calgary: Freehand Books, 2022 (first published by Macmillan of Canada, 1947)

$44.95 / 9781990601125

Reviewed by Amy Whitmore

*

A pre-schooler knocks on a minister’s door in search of God’s help in seeking revenge. Another pre-schooler navigates town with his wagon, checking in at the blacksmith’s, the livery stable, and various businesses that attract his action-seeking attention. Neither child is accompanied by an adult.

A pre-schooler knocks on a minister’s door in search of God’s help in seeking revenge. Another pre-schooler navigates town with his wagon, checking in at the blacksmith’s, the livery stable, and various businesses that attract his action-seeking attention. Neither child is accompanied by an adult.

Elementary schoolers take a gun and a hunting knife to school. On his very first day in class the gun wielder is sent to the principal’s office for shooting his teacher — with water. It is a water pistol. The older, disinterested, outcast boy keeps his hunting knife.

An apocalyptic novel about social breakdown in 21st century North America?

No, it is W.O. Mitchell’s 1947 novel, classically described as “a boy growing up on the Prairies.” In the 1930s, in Canada. It was written in an era when children had much greater physical freedom to explore their world, but stricter moral surveillance.

Who Has Seen the Wind is about so much more than “a boy growing up on the Prairies” during the Depression. It is about the external: what boys do as they grow up – watch baby pigeons, marvel at ever-propagating bunnies, flush gophers out of their holes; how adults interact; how the Prairies fail the farmers. Mitchell also wrote of the intensely personal and internal: revenge, victory, innovation, loss, power, but above all the eternal quest for understanding and meaning. Mitchell himself succinctly noted, “This is the story of a boy and the wind.” The wind is the internal search Brian takes (along with the rare adult, such as Mr. Digby and his doomed friend Mr. Hislop). The wind is giving, taking, beautiful, frightening and, foremost, impersonal.

We meet Brian as a pre-schooler determined to seek revenge on his grandmother for bossing him around and not making him a tent like the one made for his little brother (who is very sick). With the help of his neighbour Fats, Brian finds his way to a church in his quest to meet God and get help with his desired revenge. Ultimately, he meets the taken-aback, patient, lost-in-philosophical-thought Mr. Hislop, Mr. Digby’s fellow seeker. In the story’s later, adult thread, Mr. Hislop is betrayed by the church elders, who follow the lead of the formidable, narrow-minded Mrs. Abercrombie, and must leave his post as a minister of the Presbyterian church. In this dark hour it is the memory of Brian’s innocent seeking of and belief in God that helps him to maintain his faith.

Brian’s little brother recuperates and becomes the wagon-riding seeker of external adventure, the foil to Brian’s seeking of internal adventure, his quest for ‘the feeling’ first inspired by dew in the early morning sun. The pure joy he experiences becomes tempered as he grows, despite his best efforts to keep ‘the feeling’ vital. (The dead two-headed calf he and his friends see does trigger ‘the feeling’ but it’s tainted by the sense that the sight “isn’t right”).

Still, he continues the search, and at the end a day on the Prairies with Fats and Ike and their encounter with Sammy, Brian feels—

And yet for breathless moments he had been alive as he had never been before, passionate for the thing that slipped through the grasp of his understanding and eluded him. If only he could throw his cap over it; if it were something that a person could trap. If he could lie outstretched on the prairie while he lifted one edge of his cap and peeked underneath. That was all he wanted – one look! More than anything! [We know, as we follow Brian’s search, that one look would not satisfy him.]

And by the time the novel ends ‘the feeling’ is fleeting and obfuscated; dissipation is the price paid for growing up. Through Mr. Digby we know it doesn’t end for some adults, who continue to search for meaning and understanding.

The wind. The wind ties all the threads of the novel together. Mrs. Abercrombie and her vindictive quest for power—even to the point of supporting her daughter’s boycott of the Chinese children’s birthday party, which precipitates the splitting of the family and the father’s suicide. The uncaring wind, dries crops, blows away topsoil, and destroys lives. Uncle Sean’s unrequited belief in his irrigation project, and even when he’s proven right no one will believe him. The caressing wind.

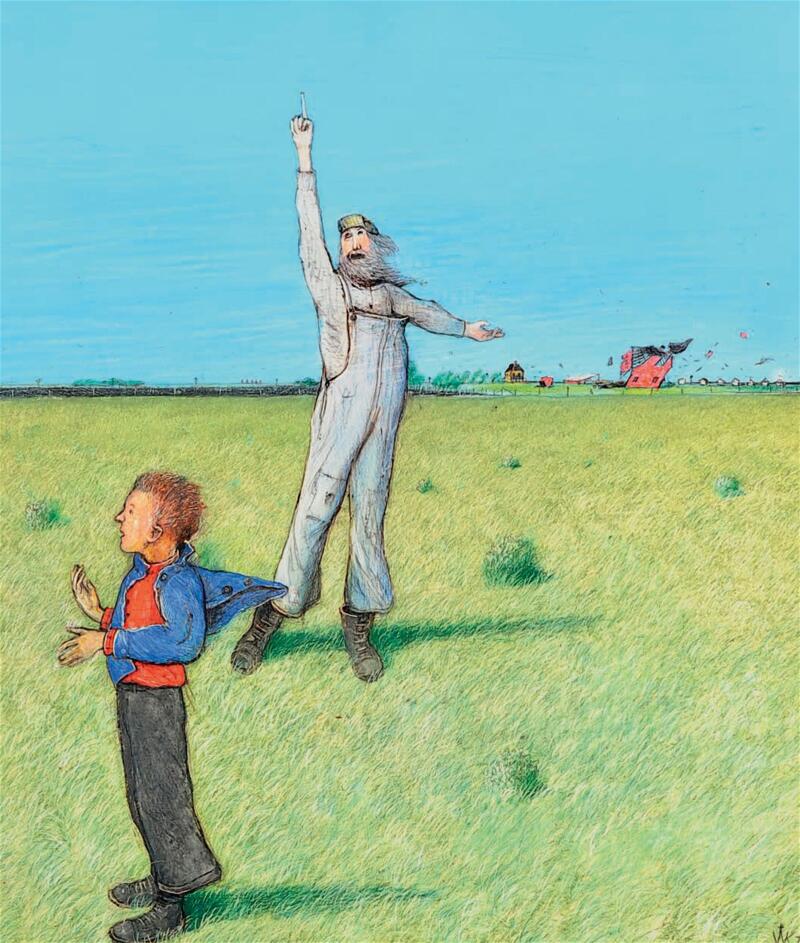

The people of the Prairies: Ben, Young Ben, and Sammy who was destroyed by the wind and Prairie yet lives on it, prophesying into the wind. Protecting his Clydesdales from Bent’s greed.

For once, the remote wind wreaks vengeance, destroying Bent’s new barn where he plans to home Clydesdales that are not his in any sense.

Ben spins tales in the pub that get him free drinks, living free on the Prairies.

His son Young Ben, is more a spirit walking with and protecting Brian than a boy. Adults reading the novel may wonder what on earth the future can be for this child. In the end will he just follow in his father’s footsteps, despite showing his own moral code in his protection of Brian? We know Mrs. Abercrombie and Presbyterian minister Mr. Powelly’s solution is vindictive: reform school. Ben showed them up as blind and arrogant when he took a job in the church in order to hide his still in the basement. Mr. Powelly, not knowing about the still, pronounces this to the congregation as the equivalent to the prodigal son returning – until the still explodes. Now he is out for vengeance, and this is one way until he can get his hands on Ben himself.

Brian and Young Ben, from opposite backgrounds but with a common communication, form a non-lingual bond. When one of Brian’s friends whirls a gopher in the air to pull off its tail, Brian senses Young Ben’s disapproval and it gives strength to his own discomfort at the act.

Brian keeps Young Ben company when he visits his father in prison. Ben does not have the same sense of the wild freedom as Young Ben, and it is only after he is imprisoned himself that he releases the owl he’s kept captive.

Unlike Young Ben, though, Brian is not of the Prairies. When he must stay with his Uncle Sean on the farm when his father is ill, he does not adapt well and play as a boy does. It is interesting to note that Brian’s mother believes Brian may want to be a “land” doctor when he grows up, so something of Uncle Sean must have rubbed off on him.

W.O. Mitchell’s writing is both eternal and of its era. It can even be clunky, as when he tries to describe Brian’s mother’s worry about her children, wanting them to “turn out right” while feeling helpless—

It was like being on the other side of a fence and jumping up to see them – a glance – fleeting, not enough for certainty – blot out – another glance – the wall again. Other people, she decided, must feel the same about the bits that had broken away from their own bodies to live on the other side of the fence to have lives of their own.

There is his brilliance in moving from Brian snuggling with his puppy in his arms, to the poplars and a flitting dust devil, to a paragraph that makes us feel the wind, the terror of the drought, the aloofness of nature, and the humour of Mitchell:

In the summer sky there, stark blue, a lonely goshawk hung. It drifted low in lazing circles, slipping its dark shadow over stubble, summer fallow, baking wheat. A pause – one swoop – galvanic death to a tan burgher no more to sit amid his city’s grained heaps and squeak a question to the wind.

The meadowlark sings through the whole novel, a symbol of hope and clarity. No one comments on or appears to notice it, and yet it sings again and again through the wind the song seekers like Brian and Digby want to sing.

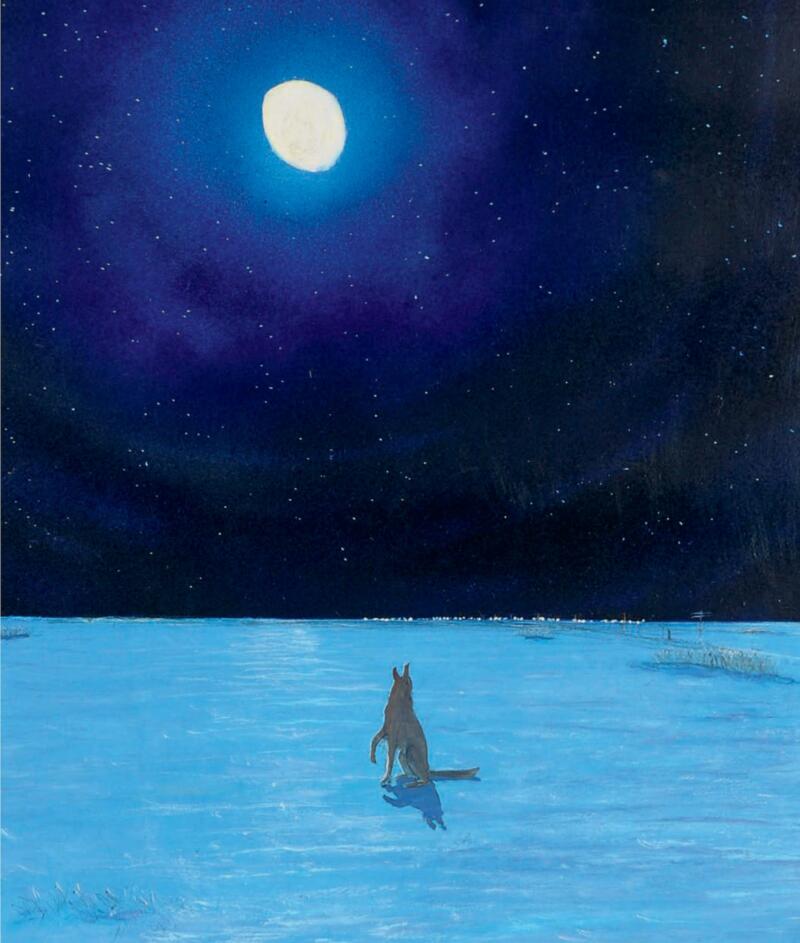

As to this 75th anniversary edition, its blue cover bears an unsettling resemblance to Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman. Otherwise it is a lovely book with exquisite colour illustrations by William Kurelek in the front. Unfortunately, the rest of the illustrations are in black and white and feel spooky, far less nuanced than the colour ones. Sammy in the wind is full of power and joy, and could symbolize the whole book—the children, the adults, the external and internal, the seeking and the aloof wind—but it is in colour.

*

Amy Whitmore: Creative non-fiction published in Black Dog Review, NB Reader, Vancouver Sun and on CBC Radio Saint John. Summer radio play commissioned by CBC Saint John. Co-winner of Atlantic Film Festival’s Script Development competition, feature category. Mary Walsh chose to read the most eccentric character. Recipient of UBC’s Jacob Zilbur Scholarship for Most Promising Screenwriter and Maxine Sevack Memorial Scholarship in Creative Non-fiction. Currently working on short stories and a novel. Master gardener student, experienced hot air balloon crew, roamer by bike of Calgary’s pathways and byways. Editor’s note: Amy recently reviewed fiction by Lenore Rowntree for The British Columbia Review.

Amy Whitmore: Creative non-fiction published in Black Dog Review, NB Reader, Vancouver Sun and on CBC Radio Saint John. Summer radio play commissioned by CBC Saint John. Co-winner of Atlantic Film Festival’s Script Development competition, feature category. Mary Walsh chose to read the most eccentric character. Recipient of UBC’s Jacob Zilbur Scholarship for Most Promising Screenwriter and Maxine Sevack Memorial Scholarship in Creative Non-fiction. Currently working on short stories and a novel. Master gardener student, experienced hot air balloon crew, roamer by bike of Calgary’s pathways and byways. Editor’s note: Amy recently reviewed fiction by Lenore Rowntree for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1801 It’s what boys do”

Forbsie Hoffman, not Fats.

I am a retired secondary school English teacher. Since my husband developed dementia and was later hospitalized with a broken ankle I have been visiting him at the hospital and reading him books. I chose “Who Has Seen the Wind” after having read him some of the “Time” novels of Madeleine L’Engle.

I came across “Who Has Seen the Wind” as a young teacher sick to death of “The Lord of the Flies”. I never got a chance to use it with any of my classes, but it had a great effect on me. Without remembering too many specifics about it, I chose it as the next novel I would read to him. (He has the same first name as the young hero, and his brother has the same name as the hero’s younger brother in the novel.)

I just wanted to let you know that Brian’s young friend is named Forbsie Hoffman. His father allows Brian’s puppy to live at the Hoffman household until it becomes less of a problem for Brian’s’ grandmother. This leads to a dead baby pigeon and traumatic epiphany for Brian–and his father, Gerald.

I hope more people will read this Canadian classic.