1802 Return of the matriarchs

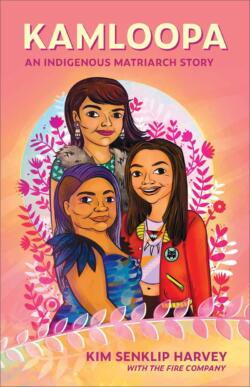

Kamloopa: An Indigenous Matriarch Story

by Kim Senklip Harvey with the Fire Company

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2020

$16.95 / 9781772012422

Reviewed by Amanda Wandler

*

This story, this ceremony is for our Indigenous Peoples, it is to give voice and illuminate the power of Indigenous womxn. It is about our unwielded power and unsuppressed Settler supremacy for the entire journey of the artistic ceremony. That is the power we are reclaiming over our storytelling ceremony with Kamloopa: An Indigenous Matriarch Story. – Kim Senklip Harvey, August 2018 [1]

This story, this ceremony is for our Indigenous Peoples, it is to give voice and illuminate the power of Indigenous womxn. It is about our unwielded power and unsuppressed Settler supremacy for the entire journey of the artistic ceremony. That is the power we are reclaiming over our storytelling ceremony with Kamloopa: An Indigenous Matriarch Story. – Kim Senklip Harvey, August 2018 [1]

I would first like to voice that not unlike the characters in Kamloopa: An Indigenous Matriarch Story, I am on my own journey of transformation, and I view this experience as one of receiving Indigenous Knowing. And although the play offered many valuable insights and elements, for the purpose of my commentary I will only be focusing on a select few.

To get the most out of Kamloopa, first-time participant(s) may benefit from first flipping to the end and engaging themselves in Miki Wolf’s appendix, “Fire Zine! A Kamloopa Study Buddy,” where Miki explores many aspects of the play including the meaning of Indigenous Knowing and Indigenous Theatre and where she also acknowledges the political context in which it was written. This includes the impact of culturally oppressive policies and laws in Canada, as well as the horrific legacy of residential schools — to “kill the Indian in the child.”

For many years the Canadian government made it illegal for Indigenous peoples to speak their traditional languages, practice their customs, and even wear traditional clothing.

This policy to commit cultural genocide against Indigenous Peoples resulted in the actual genocide of many Indigenous people in Canada. First performed in 2018, Kamloopa was published in 2020, a year before the discovery of 215 unmarked graves of Indigenous children on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, barely 500 meters from the Powwow Arbour portrayed in the play. This revelation was the catalyst to the discovery of many other unmarked graves all over Canada on the grounds of residential schools run by the Catholic and other Christian churches. These schools were intended to support the erasure of Indigenous culture in Canada and to separate children from their families, homes, and “motherland.”

In Maskwacis, Alberta in July of 2022, on the grounds of one of Canada’s largest residential schools, Pope Francis offered an apology to Indigenous people for the Church’s role in the genocide.

Although Kim Senklip Harvey’s Kamloopa portrays a journey (a spiritual journey, a journey of reclamation, and a road trip) of three First Nations womxn from the Syilx Nation, which is just one of many distinct Indigenous nations throughout Canada, its themes resonate with individuals from all nations, on the way creating a sense of connection and shared experience. Each time I picked up Kamloopa, I found myself laughing and crying. It spoke to my own feelings of inadequacy, guilt, and shame for not being more connected to my own culture and community (Secwépemc). Reading this book, I felt seen.

The reader enters the story through a reading of the character descriptions — three groups of three characters, each group being played by one actor. Actor 1 plays Mikaya, Senklip (Coyote), and Ancestor 1; Actor 2 plays Kilawna, Grizzly, and Ancestor 2; and Actor 3 plays Indian Friend Number 1 or IFN1 (Edith), Raven, and Ancestor 3.

The focus on the timelessness of the story, a common element in Indigenous Theatre, is highlighted when the playwright sets out that it takes place in “All” Times and in the Space of “The Multiverse” (p. 85; p. xi).

Kamloopa: An Indigenous Matriarch Story is separated into thirteen titled scenes, each carefully chosen to highlight the underlying meaning of the spiritual journey of the characters in the scene and symbolic of the characters’ shifting relationships to one another.

The first scene (“The Land Breathes”) is short but powerful, helping to establish the milieu with the introduction of The Ancestral Matriarchs speaking nsyilxcən, the traditional language of the Silyx, and making a maternal connection with the land in a language that has been spoken on the land for thousands of years. A soft beating sound can be heard. Raven, Senklip, Grizzly, Edith, Mikaya, and Kilawna move together as one to the beat of the Matriarch’s Land Song until a “masculine beating” — symbolic of the cultural disruption caused by patriarchal colonization in Canada — separates them (p. 4). The matriarchs then appear to be suffering and the shifters (Raven, Senklip, and Grizzly), agents of The Ancestral Matriarchs, leave on a mission on the wind river.

In the next few scenes, we learn about Kilawna and Mikaya and their relationship. Mikaya is Kilawna’s younger sister and a student studying European Art History — oh, the irony! – while discontented with her experience of tokenism in the classroom and yearning for her Indigenous culture. Kilawna, who spends most of her days working, tells Mikaya to leave the “indian thing” alone and urges her to continue studying (p. 7). Mikaya retorts back that Kilawna is a self-hating Native (p.13).

In the scene entitled “Sisters” we encounter Indian Friend Number 1 (IFN1), a mysterious Indigenous womxn whom Kilawna and Mikaya met after a night of drinking in the city, who becomes their new friend (and sister?). Mikaya enrolls herself in IFN1’s “How to Become a Real Indian” school, which includes a number of lessons:

Lesson number one: Believe in the brown (p. 29).

In my favourite scene, “End of Hibernation,” Kilawna returns home after a long day’s work, and sees smoke escaping from the bathroom of their apartment where IFN1 and Mikaya have been smudging. Kilawna then sprays them with a fire extinguisher thinking they are on fire, and covering them with the white chemicals. The scene is punctuated with IFN1 hilariously yelling, “DON’T LET THE WHITE TAKE YOU!!!” and Mikaya accusing Kilawna of wanting to “make everything white” (pp. 45 and 48).

Mikaya eventually convinces Kilawna to drive the trio to the Kamloopa Powwow by saying “its how we become real indians. We need to go and dance” (p. 48).

The most impactful element I found in Kamloopa: An Indigenous Matriarch Story was the deliberate way in which the characters are labelled and how they label themselves. The colonial term Indian, used to describe all Indigenous people in Canada, continues to have a complicated relationship with Indigenous people. It is still used in the Indian Act, and many Indigenous people still refer to themselves as indian, as a sort of reclamation of the word, and as a way to recognize the history and continued use of the term in the Indian Act. But for many other Indigenous people it is seen as a pejorative term, charged with negative colonial history which ignores the diversity of Indigenous people in Canada. Today, the preferred terms are First Nations, Métis, or Inuit, or (even better) the specific Indigenous community’s name, like Silyx.

Knowing this complicated relationship with the term, I still questioned Kim’s use of small “i” indian in place of capitalize “I” Indian. After doing some research I found that within the last three years, several (American) publications, including The Atlantic and The New York Times, have announced their official adoption of the use of capitalized “B” in Black in their style guides to describe the shared cultural identity of Black people, but I found no rhetoric discussing the use of capitalize “I” or small “i” “indian.” I assume that, along the same reasoning for the use of the term Black, Kim made the choice to use small “i” “indian” as a recognition and a corrective to the colonial mislabelling of Indigenous people as people from India.

The characters begin the play by using the colonial term indian to describe themselves, but as the characters begin to change, so do their labels for themselves, with one character exclaiming in the third act, “WE are Indigenous” (p. 72). As the characters undergo a transformation and fully embody their true selves as Seklip/Mikaya, Grizzly/Kilawna, and Raven/Edith, the play’s dialogue tags undergo a transformation as well, marking the characters’ complete metamorphosis.

Another aspect of the play that particularly caught my attention was the use of sound, including the use of nsyilxcən, the silence that accompanied the use of North American Indian Sign Language — often overlooked as the first sign language in North America — during moments of particular importance, as well as guttural growls, squawks, and howls.

What stood out the most was the music, and Kamloopa delightfully includes references to many songs and musicians throughout. The “Matriarch’s Land Song” opens the story and recurs throughout to underscore the transformation of the characters. Mikaya’s journey begins with her listening to “Colors of the Wind,” a song from Disney’s Pocahontas. This song, written by two Caucasian men, was featured in the first major motion picture where many Indigenous people were able to see themselves in the “heroine” of the movie, while at the same time unfortunately perpetuating many harmful stereotypes. Later Mikaya begins to listen to westernized music written by Indigenous artists, including “Sila,” a song by A Tribe Called Red, where she describes the group as the current “Nation-to-Nation Ambassadors” (pp. 32-33). While the play ends with the traditional drumming at the Powwow colliding with the Matriarch’s Land Song, Kim reminds us that the story has:

NO END (p. 80).

I began reading Kamloopa: An Indigenous Matriarch Story as an Indigenous reader and writer, with a name given to me by my non-Indigenous mother who raised me, feeling like I never really belonged to any culture, possessing limited Indigenous Knowledge, struggling with my own identify, and feeling alone and unseen. But as Grizzly/ Kilawna was there to “bear witness” to Senklip/ Mikaya, I know my Secwépemc matriarch ancestors are here to bear witness to me, and this publication will hold an honoured place on my bookshelf as a reminder that:

We are never alone. Together forever with the Ancestors (p. 78).

*

Amanda Wandler is a Secwépemc writer and legal professional, with a degree in law from the University of British Columbia, where she was among the first to specialize in Aboriginal law. After spending several years writing and reviewing contracts for two Crown Corporations, she decided to pursue her passion for creative writing. Amanda enjoys writing stories that challenge audiences to question their perception of the world. A play of hers was recently selected for A Broad’s Way Festival, hosted by the Western Canada Theatre in Kamloops, and she is excited about the opportunities ahead to share more of her work.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Kim Senklip Harvey, from “Protocols for the Indigenous Artistic Ceremony Kamloopa” in Miki Wolf, Fire Zine! A Kamloopa Study Buddy, August 2018.