1789 Tiny community living

Galena Bay Odyssey: Reflections of a Hippie Homesteader

by Ellen Schwartz

Victoria: Heritage House Publishing, 2023

$26.95 / 9781772034455

Reviewed by Catherine Owen

*

In the mid to later 70s, I was raised by hippie-ish parents. Which seems odd seeing as how they were religious and lived in the suburbs of Burnaby. But my father preached the eating of weeds and took us to the prototype recycling plant (a trailer run by a drunk) on the weekend to teach us how to separate cans and bottles; my mother grew bean sprouts on the counter, made her own yoghurt and granola, and didn’t let us consume white sugar. So Ellen Schwartz’s saga of true hippie life in the Galena Bay bush didn’t seem too alien to me, though, of course, her choice of lifestyle made for a whole lot more work. First off, I must note that this book is wonderfully written (minus a few overly descriptive passages that fall into the clichés of rain in “fat drops” and hail “like machine-gun fire”) and edited exquisitely. What a relief. These tales of adventures on the land are too often told by those who don’t really write (but think it’s easy) and thus, while the narrative may be compelling, the dearth of style or the laxness with syntax render the read tedious or frustrating. Conversely, Schwartz is a well-published writer in multiple genres and this book is a smooth and enticing read because of her fastidious and engaging tone. I read it every morning at breakfast (not of granola, alas) and could hardly put it down, thinking about Ellen and her husband Bill’s education in the wilderness throughout the day.

In the mid to later 70s, I was raised by hippie-ish parents. Which seems odd seeing as how they were religious and lived in the suburbs of Burnaby. But my father preached the eating of weeds and took us to the prototype recycling plant (a trailer run by a drunk) on the weekend to teach us how to separate cans and bottles; my mother grew bean sprouts on the counter, made her own yoghurt and granola, and didn’t let us consume white sugar. So Ellen Schwartz’s saga of true hippie life in the Galena Bay bush didn’t seem too alien to me, though, of course, her choice of lifestyle made for a whole lot more work. First off, I must note that this book is wonderfully written (minus a few overly descriptive passages that fall into the clichés of rain in “fat drops” and hail “like machine-gun fire”) and edited exquisitely. What a relief. These tales of adventures on the land are too often told by those who don’t really write (but think it’s easy) and thus, while the narrative may be compelling, the dearth of style or the laxness with syntax render the read tedious or frustrating. Conversely, Schwartz is a well-published writer in multiple genres and this book is a smooth and enticing read because of her fastidious and engaging tone. I read it every morning at breakfast (not of granola, alas) and could hardly put it down, thinking about Ellen and her husband Bill’s education in the wilderness throughout the day.

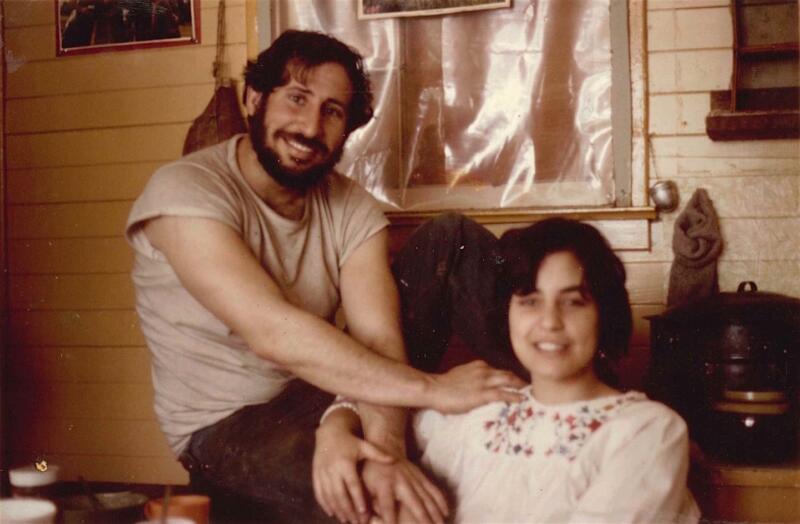

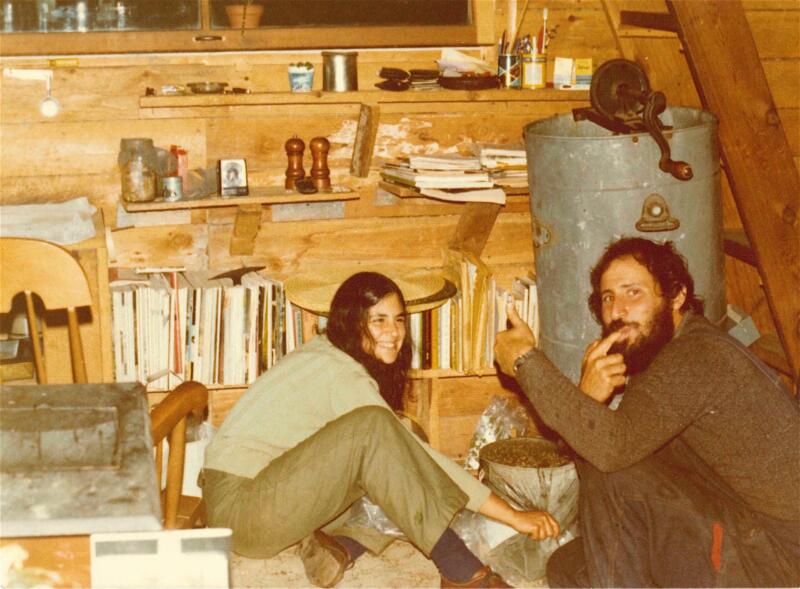

She begins her story with a depiction of her upper middle-class foundation in New Jersey, one that led her to desire a wilder life as a contrast to the “French colonial-style furniture…[and] classical music” that defined her family home. To me it’s not ironic but utterly apropos that, as she states later in the book, “the post-war affluence that we baby boomers enjoyed gave us the leisure to reject it.” Thus, after becoming both disillusioned and enlightened with questionings, Schwartz determines to work on a farm in 1971 with her friend, Paul. While there, she meets members of the supposed commune who have decided they will move to Canada to go “back to the land,” and eventually falls for her husband, Bill, a love that leads her to join part of the group on the drive up to BC. Here, two of them settle in Kaslo, while Paul, Bill and Ellen select a less-logged property not far from Revelstoke and Beaton (I’ve been there while researching my book on Mattie Gunterman so could place myself even deeper in the landscape!).

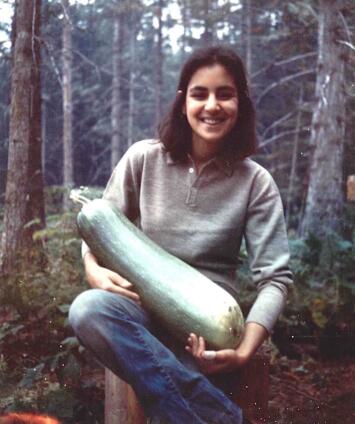

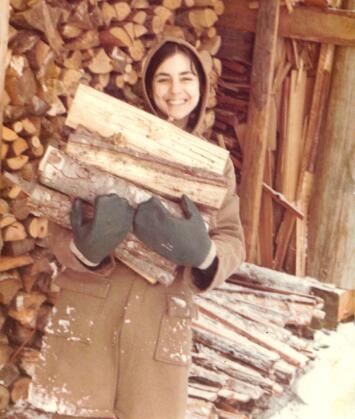

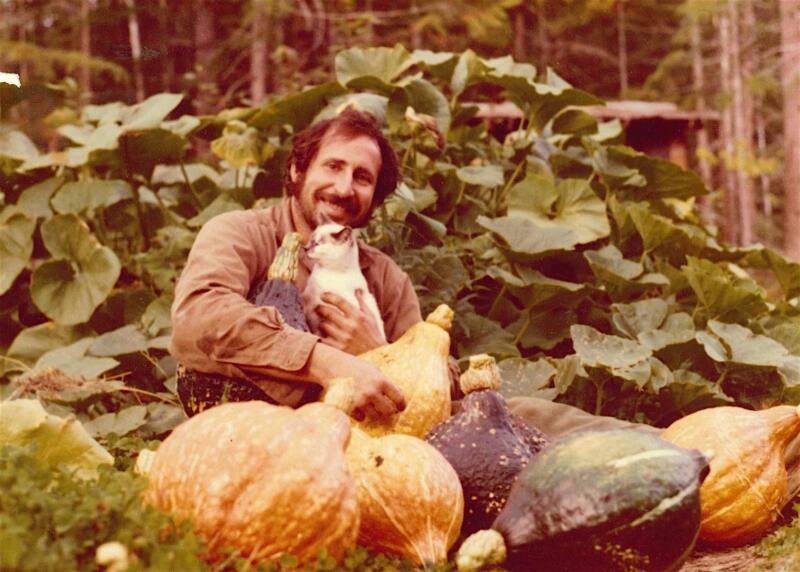

And thence commence many accounts of the power of the mind to learn. Ellen arrives in the bush knowing next-to-nothing, even panicking within, “I can’t do this…I’ve made a terrible mistake…I deserve to quit,” and over the subsequent years, she contributes to the clearing of the lot, the construction of their cabin, tunnels out a water line, digs out a stony garden and plants it, makes an outhouse, raises and kills chickens (a hilariously tragic part of the narrative when they realize they have to slaughter all the roosters but one, a brat of a bird that they dub Abdul), keeps bees, builds a sauna, and even grows to love skiing.

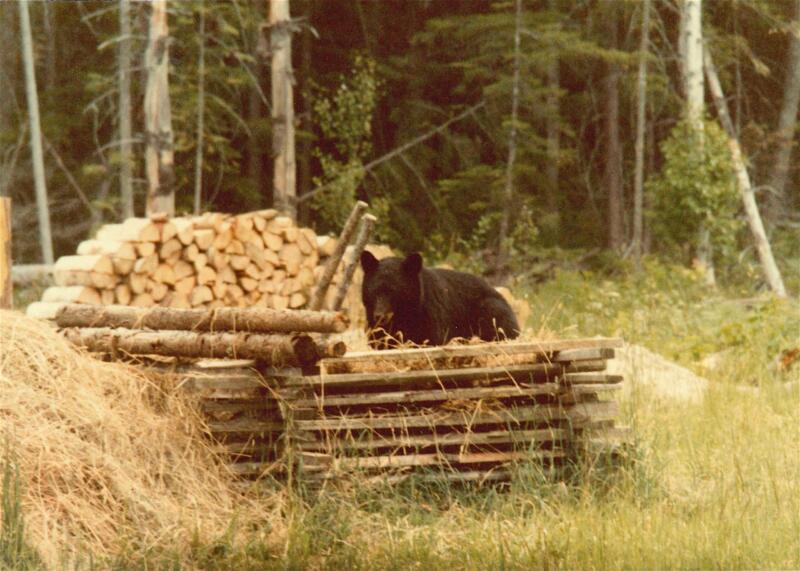

Along the way, they must grow accustomed to tiny community living: the erratic mail service, the odd grudges, the rampant generosities, the conflicts between hippies and loggers, and the dangers of isolation that create threats from wild animals, getting lost, or becoming injured. Throughout Schwartz’s memories, threads extend from her environmental awareness (particularly in a sometimes-troubled devotion to vegetarianism) to feminist consciousness (especially potent is her struggle to assert her desire to join a dance company for a year as her husband postpones his own work as a teacher), while class privilege is interrogated and even her own youthful reactions to her parents’ difficulties with accepting their daughter’s challenging lifestyle (“When I look back, I cringe at how obnoxious I must have been.”)

The book is divided into clear and compelling chapters, though I questioned the need for sub-titles at times as the dividers between paragraphs seemed sufficient. Also, there are seven sections called “Making a Living” that are set off from the rest of the text with not only titles but a different font. It’s a real toss-up as to whether this separation was necessary. On the one hand, their money-making pursuits always happened beyond Galena Bay through teaching and administrative or manual labour; on the other, the two endeavours: making a home in the wild and creating ways to ensure this occurred, appear entwined to me, yielding and feeding within one vital ecosystem.

Their adventure slowly winds down as they are faced with the realities of being parents around 1980. Although they still spend time there with their newborn, then toddler, Merri, by the time their second daughter, Amy, is born they realize “we’re never going to live there again” due to a lack of proximity to schools and the increased challenges of the wilderness for children. Yet during those eight years, Schwartz solidified more of a bond with the land and with her mate than she could have living anywhere else, proving to herself that she was capable of nearly anything and, in the end, honouring the sweet “naivety … the kind the world needs,” that turned a move to Galena Bay into a true odyssey of tangibly spiritual and psychological depths.

*

Catherine Owen was born and raised in Vancouver by an ex-nun and a truck driver. The oldest of five children, she began writing at three and started publishing at eleven, a short story in a Catholic Schools’ writing contest chapbook. She did her first public poetry readings in her teens and Exile Editions published her poetry collection on Egon Schiele in 1998. Since then, she’s released fifteen collections of poetry and prose, including essays, memoirs, short fiction and children’s books. Her latest books are Riven (poems from ECW 2020) and Locations of Grief (mourning memoirs from 24 writers out from Wolsak & Wynn, 2020). She also runs Marrow Reviews on WordPress, the podcast Ms Lyric’s Poetry Outlaws, the YouTube channel The Reading Queen and the performance series, 94th Street Trobairitz. She’s been on 12 cross-Canada tours, played bass in metal bands, worked in BC Film Props and currently runs an editing business out of her 1905 house in Edmonton where she lives with four cats. Editor’s note: Catherine Owen has also reviewed books by Tara MacLean, Caroll Simpson, Hilary Peach, John Armstrong, and Jason Schneider for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster