1754 The weight of the earth

Red Obsidian: New and Selected Poems

by Stephan Torre

Regina: University of Regina Press, 2021 (Oskana Poetry & Poetics)

$19.95 / 9780889777750

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

*

There is an old story on this coast, told by people working daily with the Earth, turning it into land, fields and crops. It is called ‘The Farm.” These industrial artworks are repeated over and over again from California to Alaska. The stories told of them are romances of human love and dreams, set within the beauty of the Earth. A little spread in Flathead Country or the Peace. That kind of thing.

There is an old story on this coast, told by people working daily with the Earth, turning it into land, fields and crops. It is called ‘The Farm.” These industrial artworks are repeated over and over again from California to Alaska. The stories told of them are romances of human love and dreams, set within the beauty of the Earth. A little spread in Flathead Country or the Peace. That kind of thing.

These are often stories of damaged men and toughened women. To have a family in them, a couple needs some social space. Because the biggest piece of society in the West is the Earth, the space often comes from that. As Stephan Torre relates in Red Obsidian, it doesn’t always do a great deal for the beauty of the space, or the love. Anyone telling this story must come to terms with that Earth and that love one way or another: either to nurture them or to kill them. As an example, here’s what Torre writes in “We Went Out to Make Hay” of an experience parallel to that of the young poet Pat Lane working as a ranch hand in the Cariboo:

We went out to yank the breaking plough down

……….through the slough, rolling

……….up peat like dark liver

……….from under the deep grass

We went out with good steel on our tongues

We went out with barrels of diesel and hydraulic oil

……….out with dried fruit and bullets in our trousers

For Stephan Torre, this act of transformation and destruction creates the fields of a farm, an act (in part) of love for a woman that is also destined to drive a wedge between them. Tough stuff.

When are you coming back, the women whispered, maybe you

could guess

……….[from “We Went Out to Make Hay”]

That Torre manages to turn this tragedy into a comedy is a testament to his strength, but, as he relates, such a life on the cutting edge of society and Earth is bewildering to live through:

After I kill

and gut another gift

of glacial blood — sleek

moon-dappled green

and blue body with a rose

blush of twilight in its belly —

a loose hook

snags and stings

my throat.

……….[from “Salmonidae”]

What a price to pay to harvest the energy of the Earth and Sky that pass through, over and past a farm! Social and Industrial products flow in (fuel, tractors, poetry and stuff). Bread, seed oil, hay, sour gas, cattle and poetry flow out. In a good year, farms are engines, combine harvesters set up between earth and sky, separating them into wheat and chaff. Hopefully it is enough to pay the social bills that accumulate. A family can be supported from the labour such shared space makes possible. Love can be made there, even. That’s the dream. It’s rarely enough to repay the debt to the Earth. Or to those one loves. When the men come in from the killing, mystery remains. Their wives, who are part of the killing, too, greet them at the door with a “how hungry are you?” Pretty hungry (from “Making Hay”).

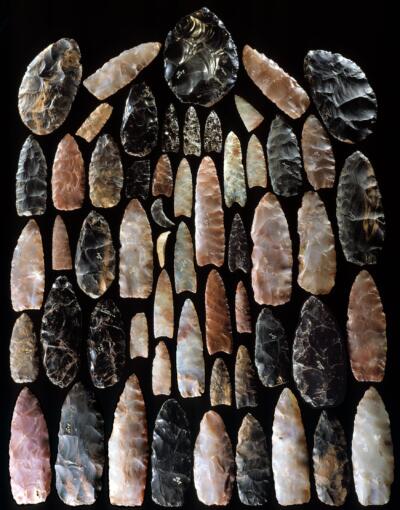

One of the strengths of Red Obsidian is that Torre links settler and Indigenous cultures. His walk through hunger dances through passion, confusion, determination and plain blockheadedness, but always there is the caldera on the horizon, where the Earth is made new as obsidian: beautiful, volcanic, and breakable — long used by Indigenous peoples to create sharp knifes, arrowheads and spear points. Red obsidian is a rare variation, coloured by mineral impurities. In modern spiritual work, it grounds individuality within human social lives. It does so in Red Obsidian as well: something to be sought off the edges of the farm, at the crest of the mountains — in other words at the boundary between Earth and sky, and out of the farm completely.

In many cultures of the North East Pacific shore, the Earth that was surveyed into land and cleared or fenced to create the first farms was already human social space, enriched over hundreds of generations. Families have long been supported from the labour such a space makes possible. Love can be made there. Survival does, however, require killing: deer, elk, bison, bears, salmon, and so on. In response to this breakage from the world, Indigenous cultures have built up elaborate spiritual protocols to intercede and heal the psychic wounds of this slaughter. Torre has done the same. His protocols are his poems. They actually shake with the pounding of the pistons in his tractor (his obsidian point):

………………………..So I utter

to my trusted cold contraption that mocks

with the smoothest idle my stuttering breath

and ligaments, this integrity of heavy iron,

……….[from “Last Ones”],

before it all turns to rust the colour of red obsidian.

Elsewhere in the story, a man strikes a stone against obsidian in a skillful knocking to produce a point as clear as a crack of stone in the ear, extended as he casts a loved one’s ashes out into the water:

……………………………grind and burn us

back to mineral this chalky powder

that stays. in the pores of my hand

grooves of my palm where words begin and end

ash of those we’ve loved my hands keep.

……….[from “What Won’t Release”]

The Earth just won’t go. It is bound with the hunger.

Torre identifies this drive to break the Earth apart to release its energy as the nature of dreams, which break everyday life apart and recreate it in new forms. What remains of old forms, old selves even, are shards, broken pieces of shared life, as sharp as stone blades, with the capacity to pass that breaking energy on, and with it the dream that pushed a hand to create it.

The poems in Red Obsidian are shards of that kind: some big; some small. In the process, Torre’s English has been knocked down to a chain of nouns, almost without connective tissue. The stanzas end up as spear points with fine, sharp chips around their edges. In those reflective black glass points, Torre sees himself:

Obsidian scatter and coyote bones

in the alkali silt under my boots,

raucous old raven leading me back uphill

past the steaming hot spring to empty

eagle nests in chiseled rim rock, and on

into a juniper stubbled caldera.

……….[from “Salt Land”]

Everything is the land here. Out of the death of water and mountains laid flat and white as salt, Torre has walked to the caldera, where the fire trees, junipers, wait, past the old chert and obsidian quarries of the ridges, to the fire that is the beginning of the world. In a poem of death it is an exquisitely physical affirmation of life.

The mirror is old. Robinson Jeffers told it on the California coast of Torre’s childhood: a civilization tried to escape itself by exploring a new continent, able to live only in novelty, was turned back by the Pacific and could go no further. Jeffers’s solution was to turn from society and rage. His poetic descendent, Theodore Roethke drove out to the coastal beaches until his tires spun in the sand and he had to walk instead. Torre picked up those footsteps and kept going.

This tradition also includes Gary Snyder, Kenneth Rexroth and Cid Corman, who all crossed the Pacific to pick up the trail. Torre walks those footsteps through his own versions of the Japanese ceremonial form, the tanka, expanding his flint-napping piles into linked social-environmental-spiritual images. Here’s an example of what one of those tankas looks like in the hands of an obsidian carver and tractor driver:

how long before the dark

island shore breaks free

and a green wave rises

to swallow my shadow?

……….[from “Under Atlin Mountain”]

Here, his stone-napping hand steers the gentler but no less rhythmic digging in of a paddle and the wait to hear the water’s response in the old Zen image of the sky and mountains intermingled. As in all of Torres’ poems, it transfers great physicality and great craft.

While Torre has been walking this path, however, a whole poetic tradition has been built in this place on a different foundation — a most welcome and powerful one that includes the voices of women, Indigenous people, LGTQ2+ poets, and so many more. Yet, as Torre foretells:

When will you come back, they asked, when do you think

………..you might come back

………..the women wondered

[from “We Went Out to Make Hay”]

The answer Torre gives is now, at the end that is the beginning, in Red Obsidian, a bundle of spear points he has carried from South to North along the continent’s spine. Here, earth and craft speak as one. A man is only dreams against this earth, knocked into understanding in the way he knocks micro blades off stone and pounds across the playas in the diesel engine of his machines until the land knocks splinters off him in turn, these poems of red obsidian, these giant, decorative Clovis culture blades used by young men on the search for the last megafauna. The Columbia Mammoths might all be gone now, but there are still the mountains.

Like the gorgeous coloured Clovis points of the Fenn Cache, not so far as the crow flies from Torre’s roots in Montana, a collection of ceremonial trade items of great value and skill carried a long distance in a skin bag, these are not practical, everyday objects. They are ceremonial poems flaked out into selves — into tools.

All the time, the calderas loom on the horizon. Always the dreams are just there, the breaking open and breaking off, these tools that can be passed from hand to hand and can be used — not to bring down big game, but to turn the edge of the world until the earth’s weight is right in the hand.

This is the work of a master carver.

*

Harold Rhenisch has written some thirty books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for The Wolves at Evelyn (Brindle & Glass, 2006), a memoir of German immigrant life from the Similkameen to the Bulkley valleys. His other grasslands books are Tom Thompson’s Shack (New Star, 1999) and Out of the Interior (Ronsdale, 1993). He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and has worked closely with the photographer Chris Harris on Spirit in the Grass (2008), Motherstone (2010), and Cariboo Chilcotin Coast (2016), as well as on The Bowron Lakes (2006), all published by Country Lights; and he writes the blog Okanagan-Okanogan. He is working on Commonage, a history of the Okanagan region, highlighting the American history of Father Charles Pandosy and situating the roots of the Commonage land claim in the North Okanagan in American colonial practice in Old Oregon. Harold lives in Vernon. Editor’s note: Harold Rhenisch has recently reviewed books by Don Gayton, Calvin White, Garry Gottfriedson, Susan Smith-Josephy & Irene Bjerky, Bill Barlee, and Fred Braches for The British Columbia Review. His recent book Landings (Burton House, 2021) was reviewed by Luanne Armstrong; and The Tree Whisperer (Gaspereau, 2021) was reviewed by Adrienne Fitzpatrick.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

9 comments on “1754 The weight of the earth”